Digital Gallery

All Themes

Discover this rich selection of digitized posters and other ephemera on HIV/AIDS from 1981 to the present day. All the items are part of the National Library of Medicine’s Digital Collections.

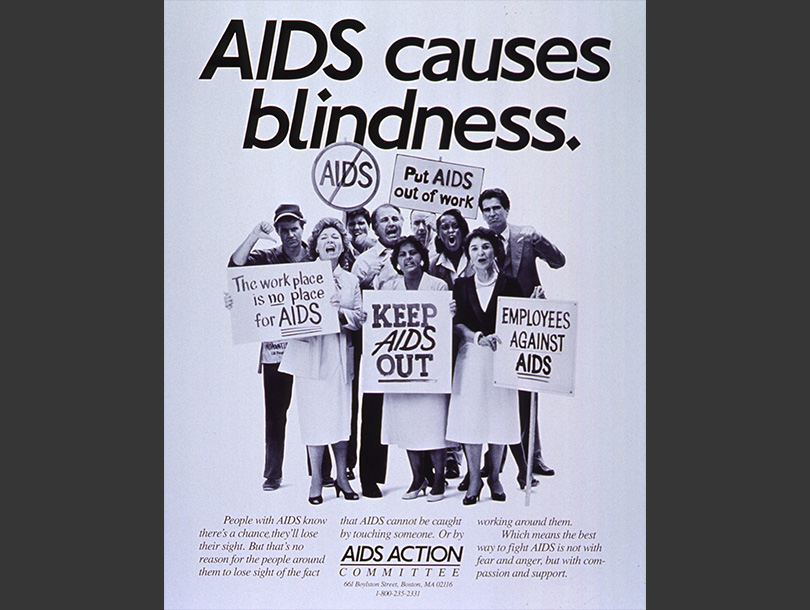

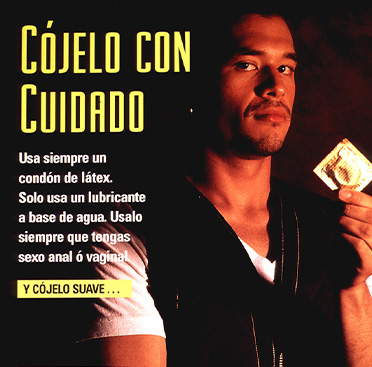

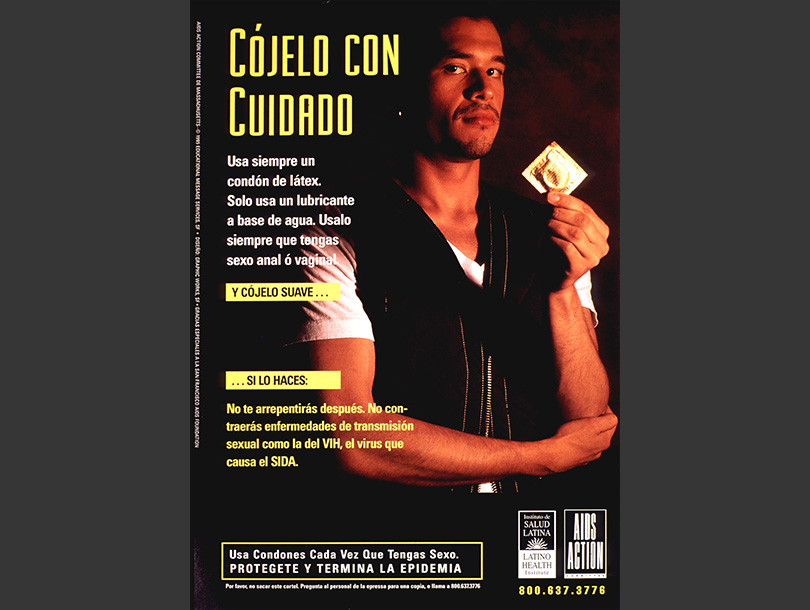

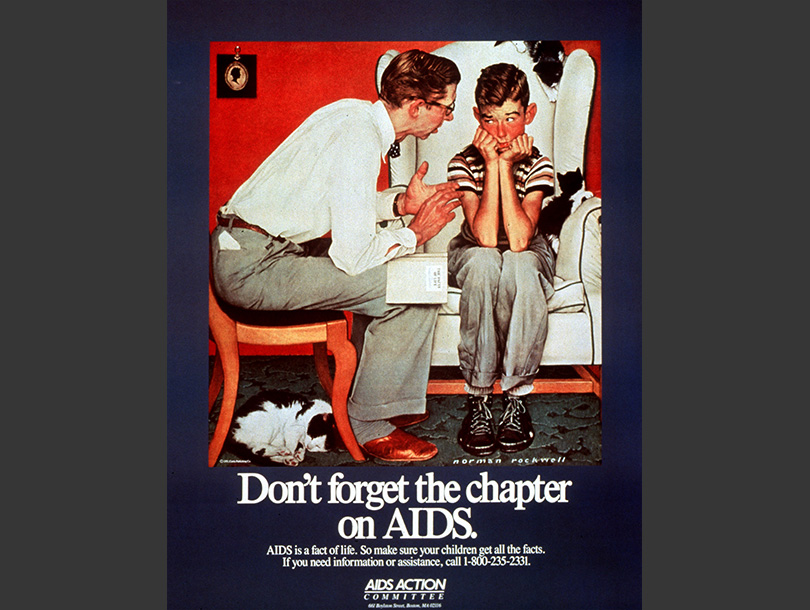

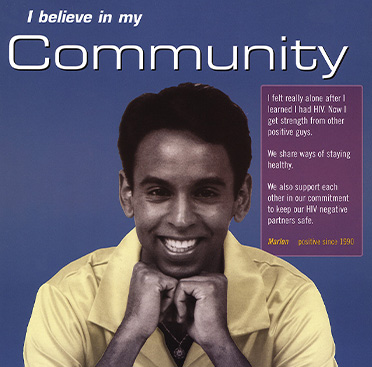

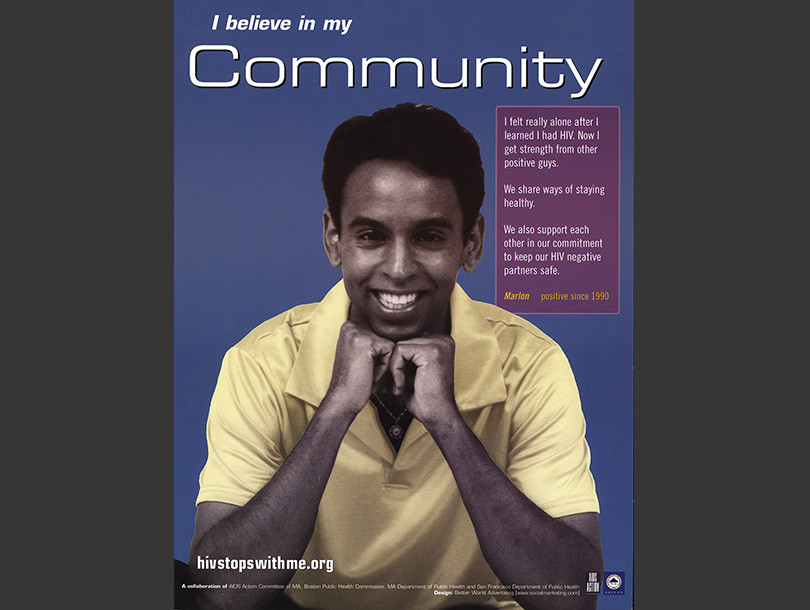

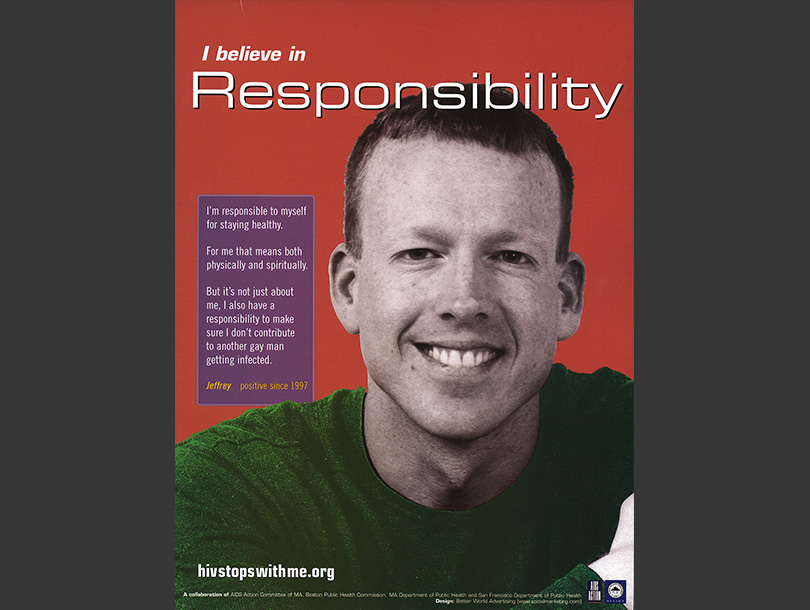

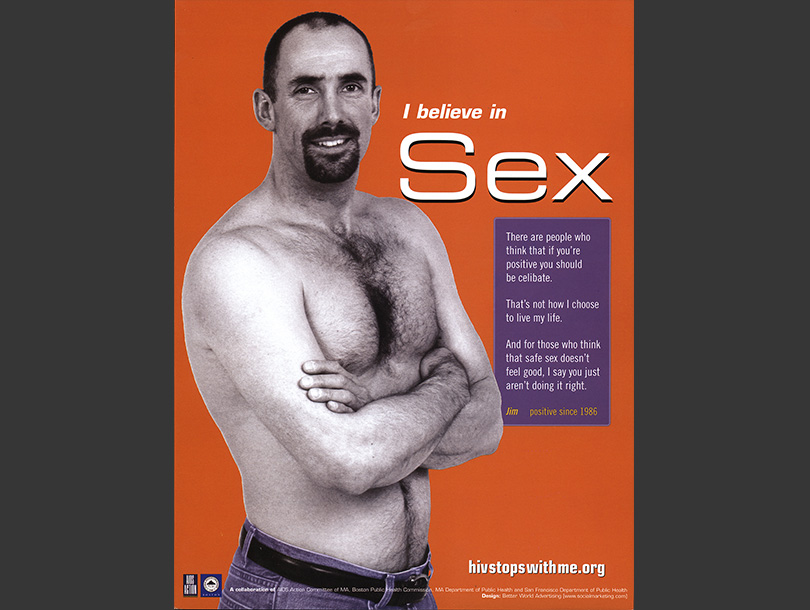

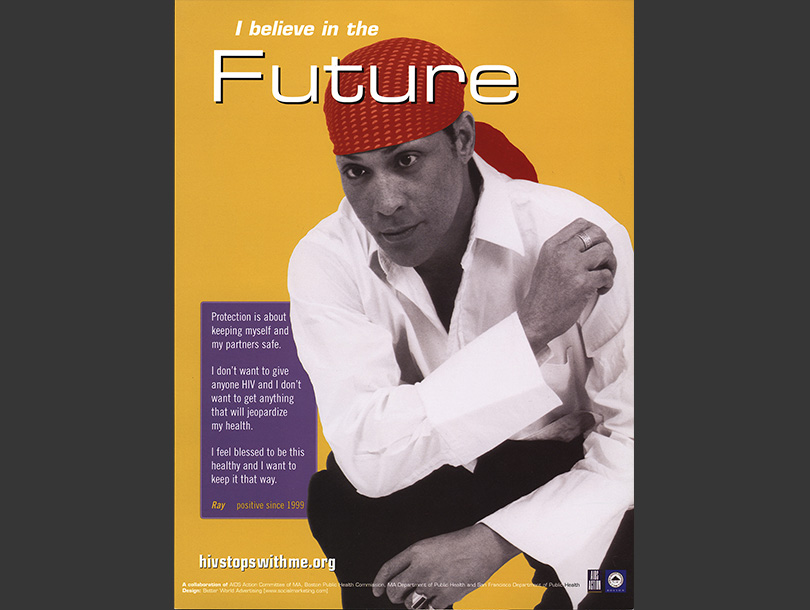

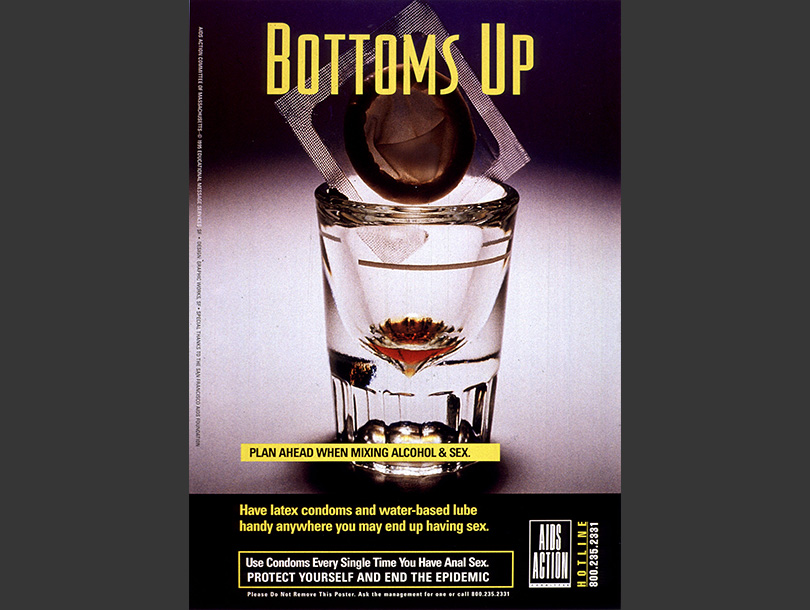

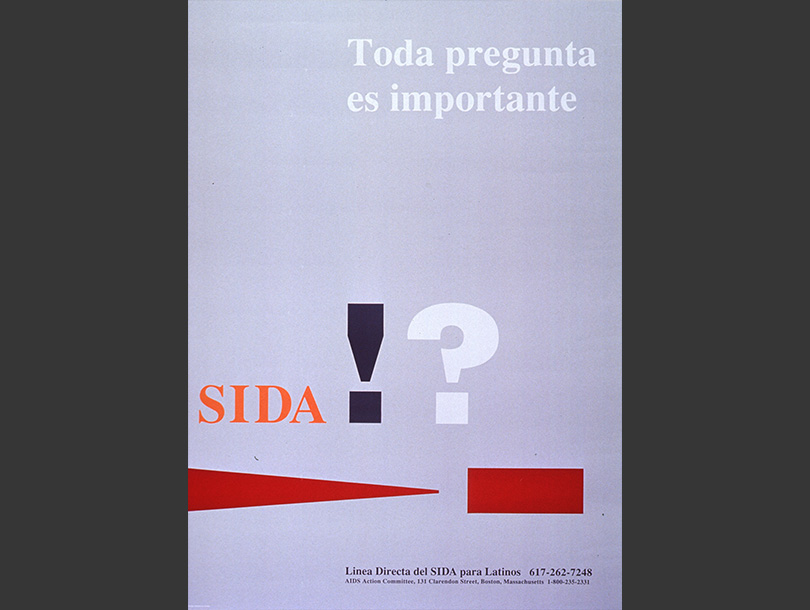

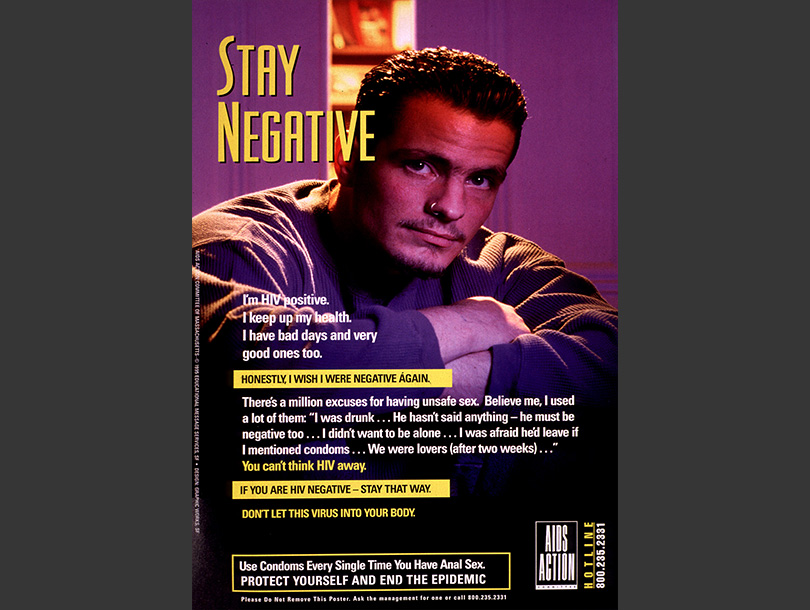

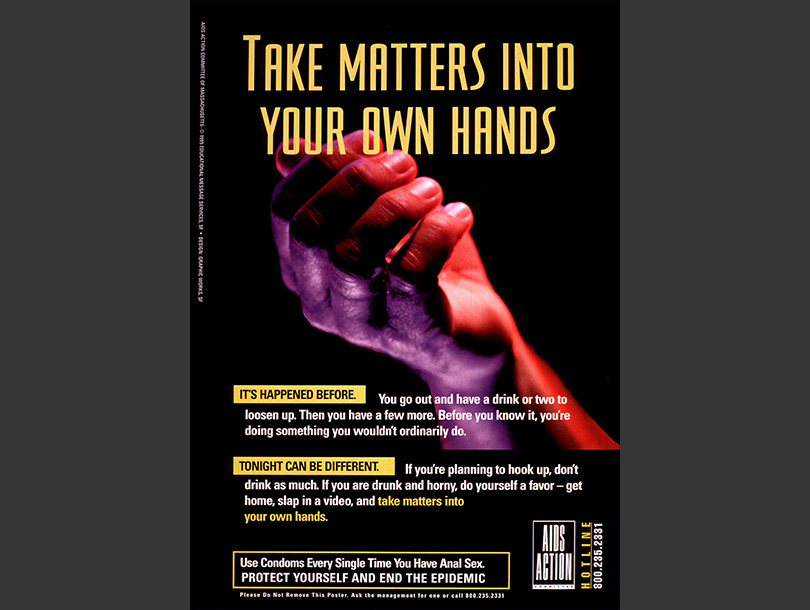

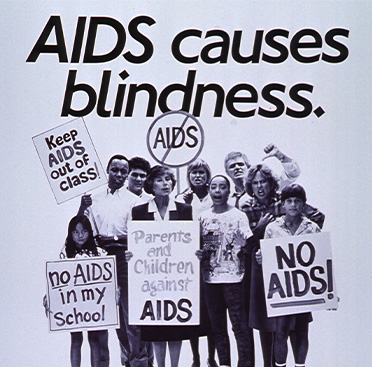

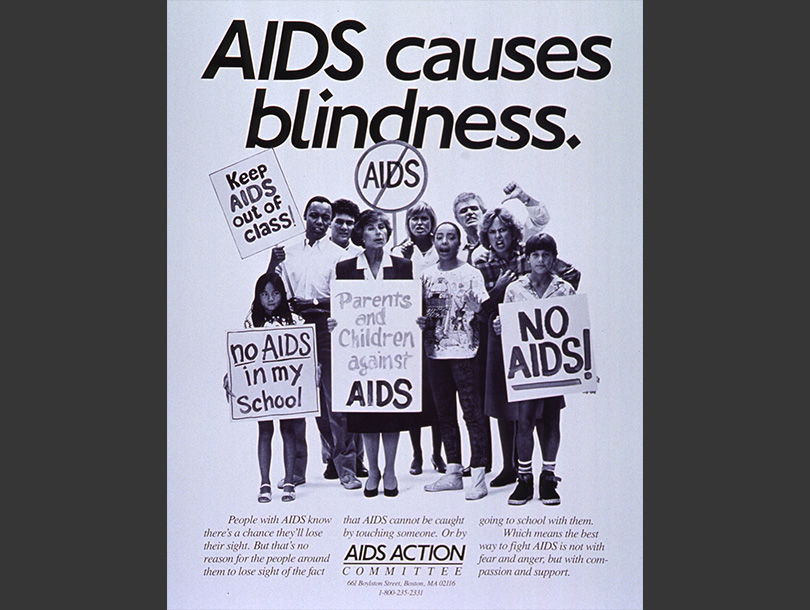

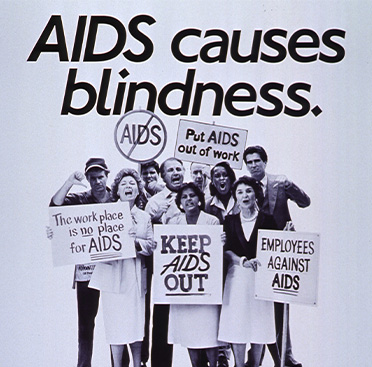

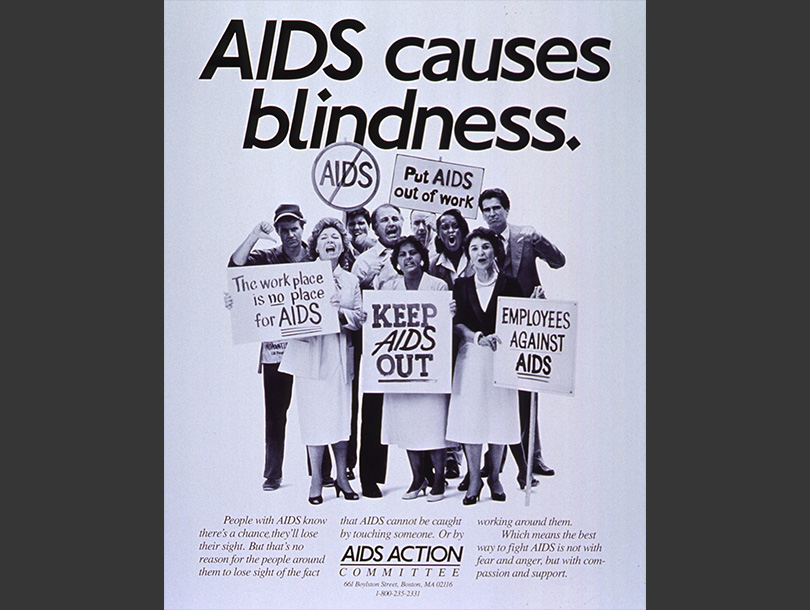

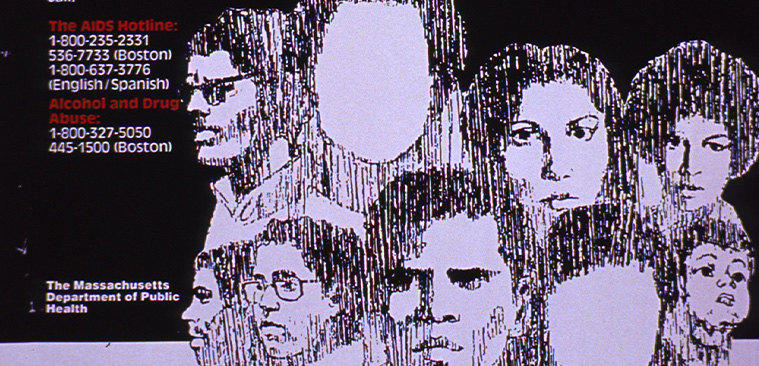

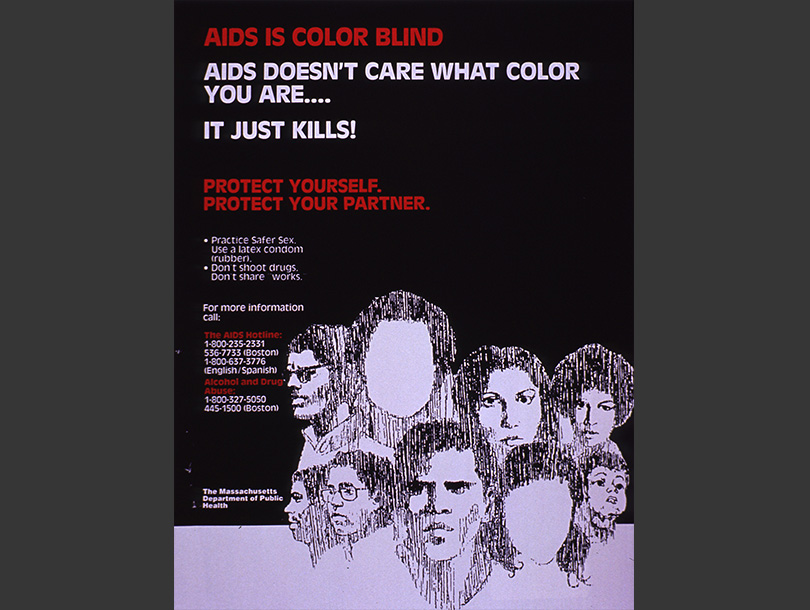

AIDS Action Committee

The AIDS Action Committee (AAC) began in 1983 in the basement of Boston’s Fenway Community Health Center, one of the first clinics in the country to treat people with AIDS. For more than thirty years, AAC has focused on AIDS advocacy, prevention, and support for those living with the disease, even as the kinds of images and words used in public health campaigns have changed over time. Early publicity focused on reaching various populations in Boston and New England to fight potential discrimination against people with AIDS at the same time that AAC worked to share specific strategies for keeping a diverse range of people healthy. By offering clear and concrete advice to people whose behaviors put them at risk of contracting HIV as well as the general public, AAC’s inclusive campaigns helped to prioritize AIDS in local and national conversations. To date, the organization has worked with more than half of the people diagnosed with AIDS in Massachusetts.

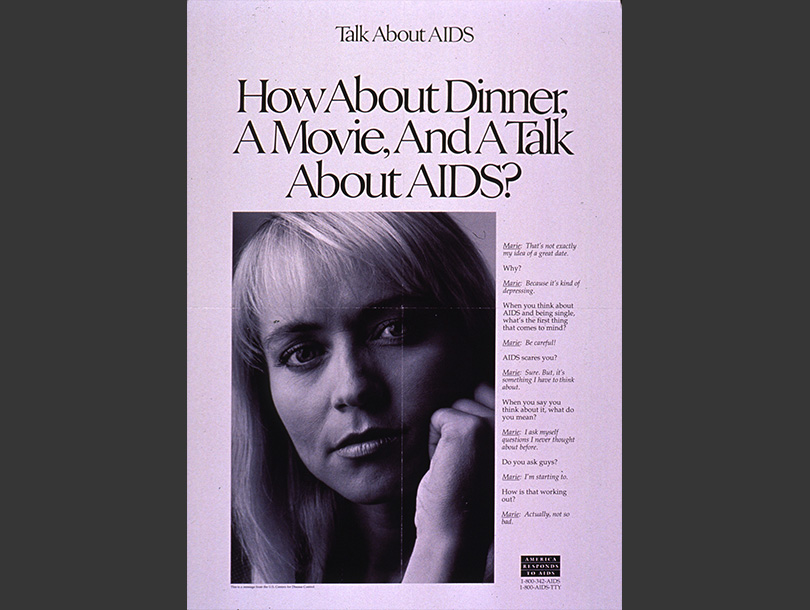

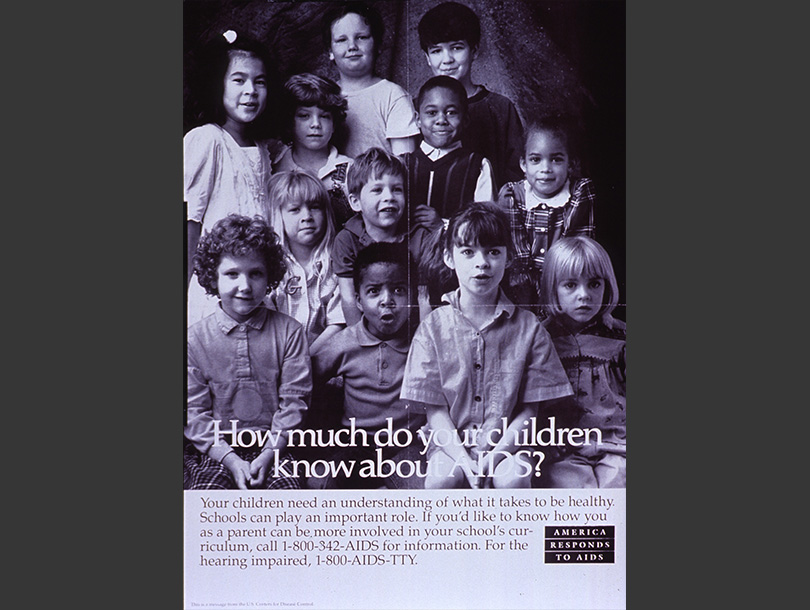

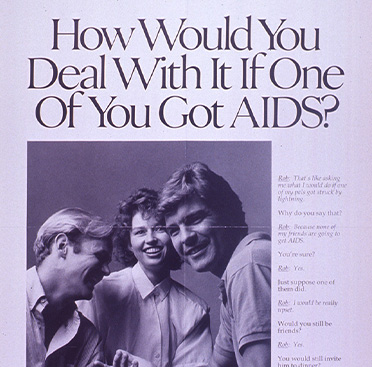

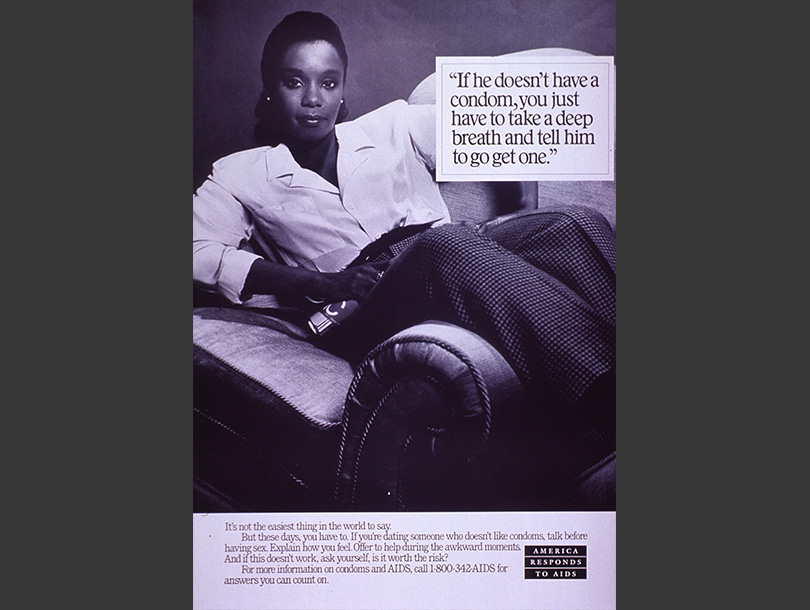

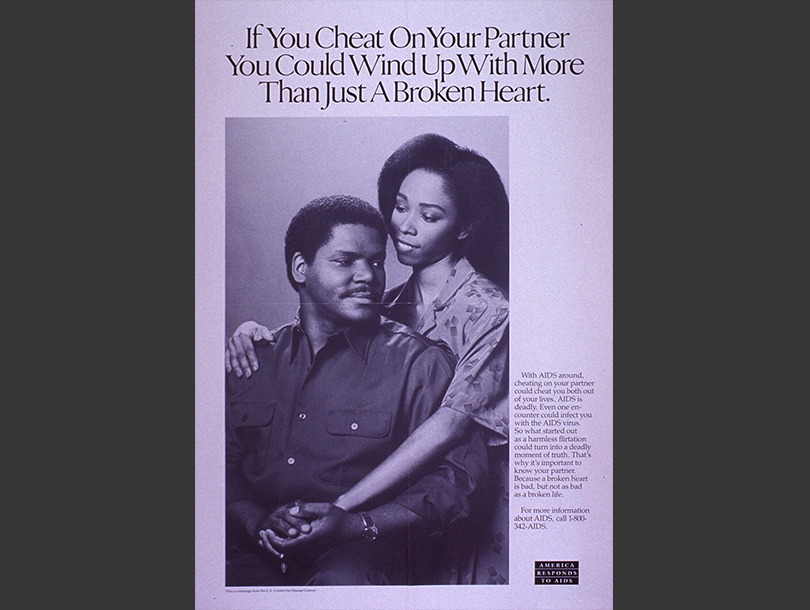

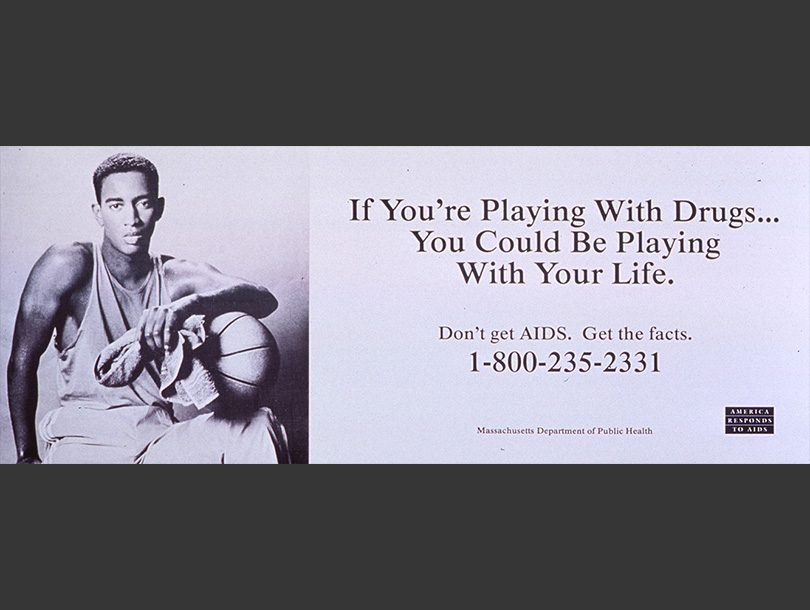

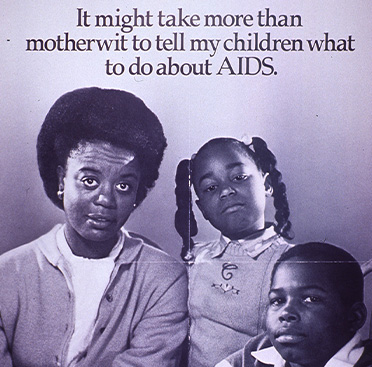

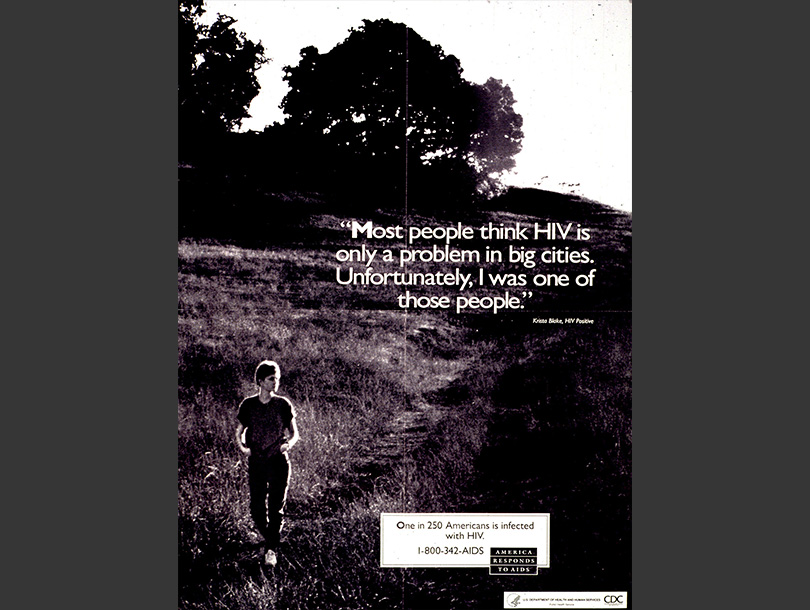

View images in this themeAmerica Responds to AIDS

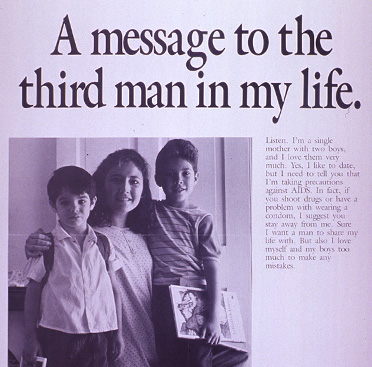

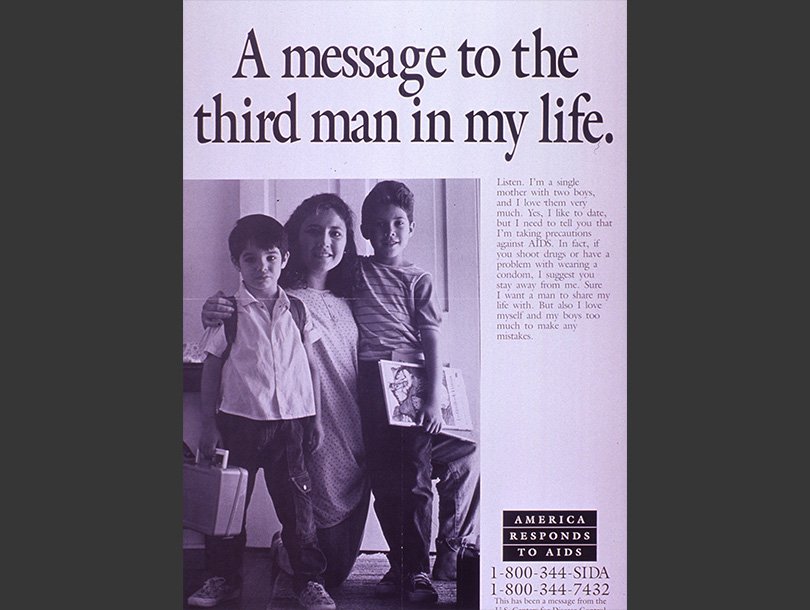

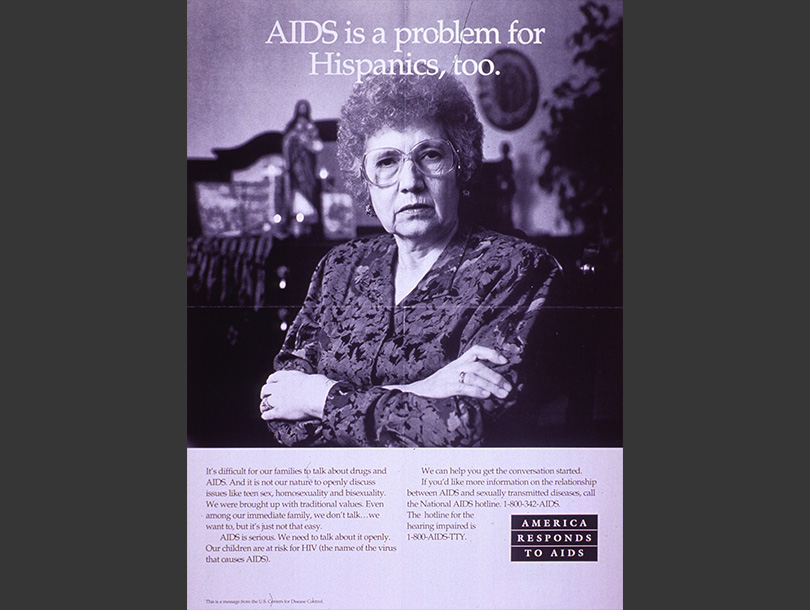

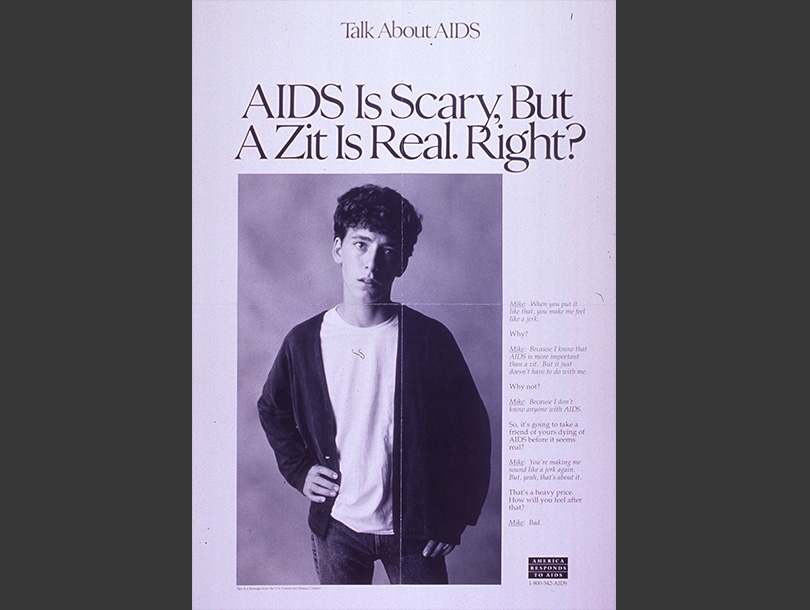

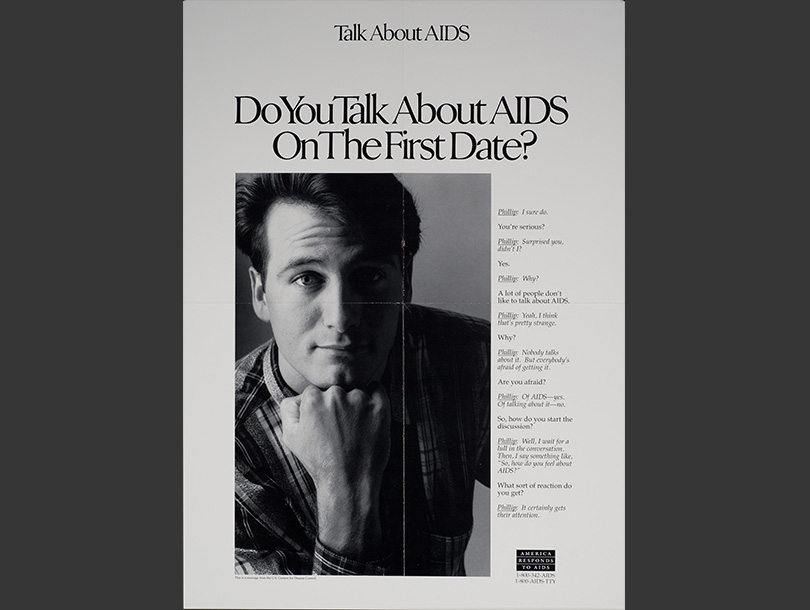

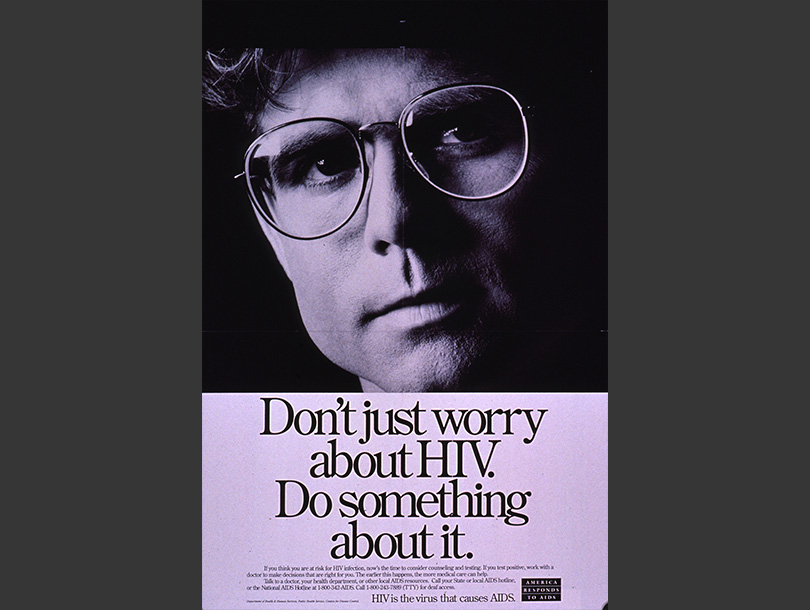

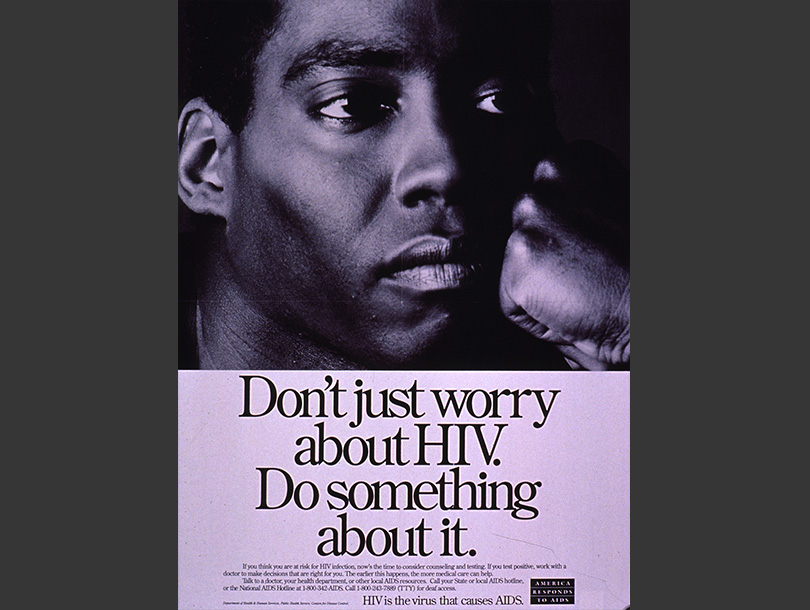

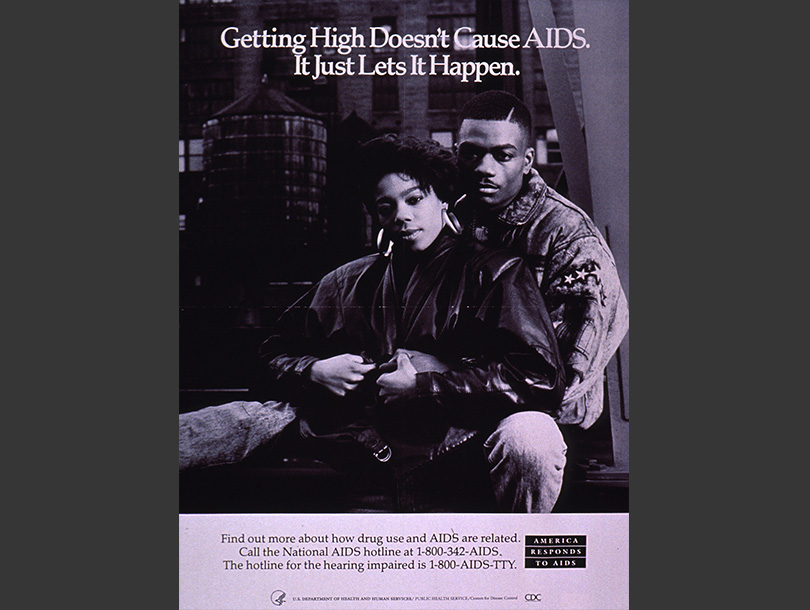

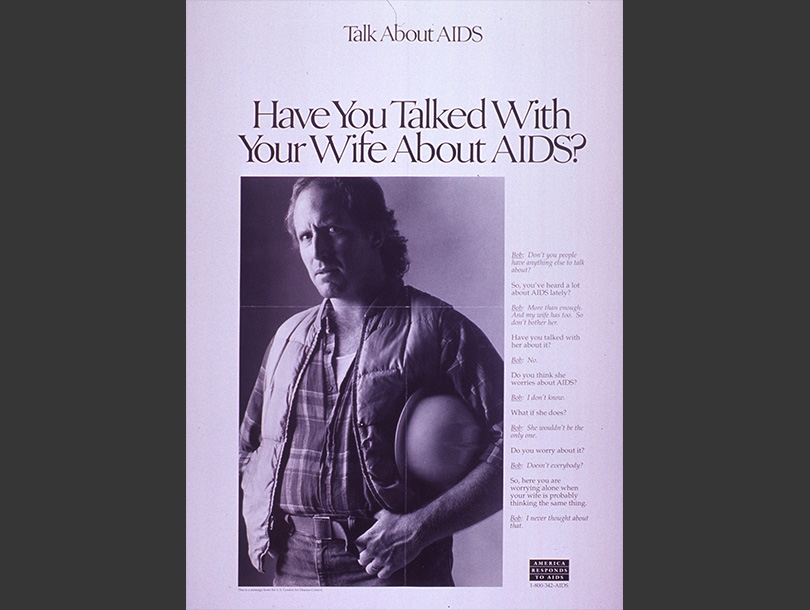

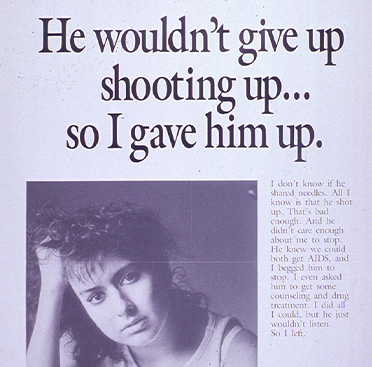

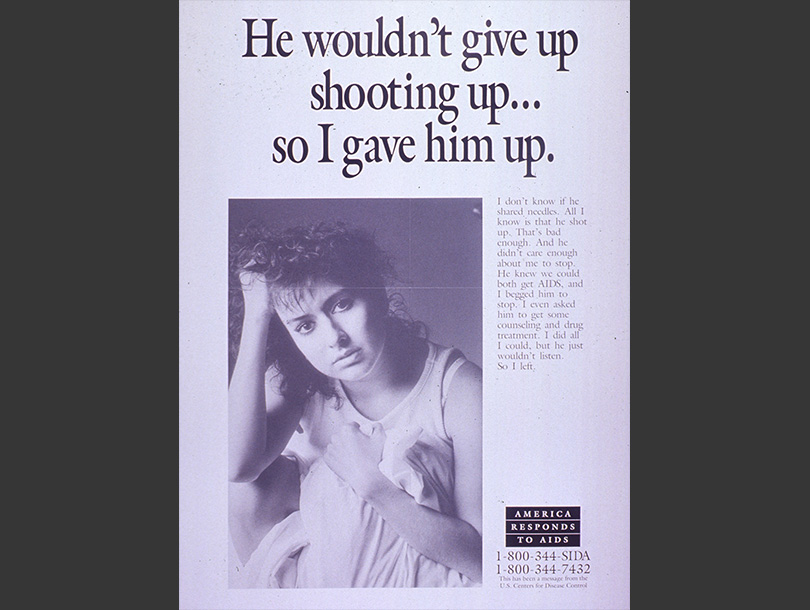

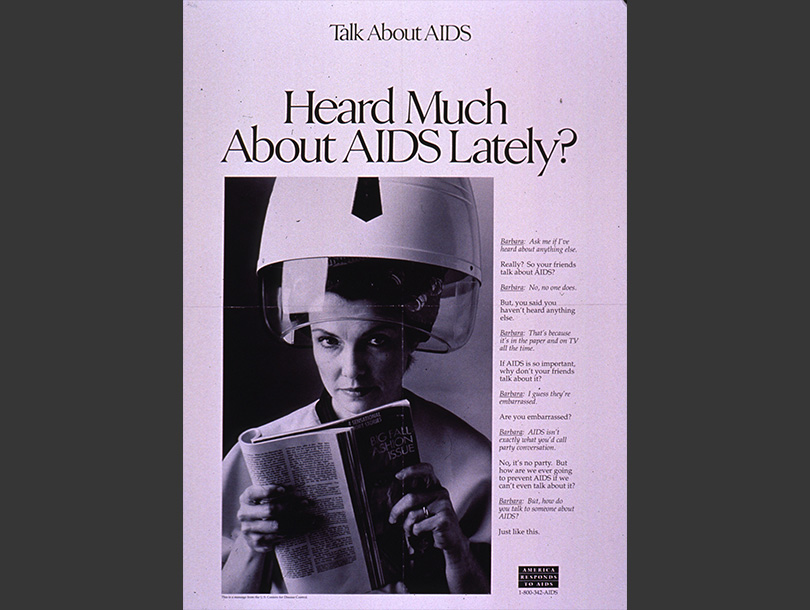

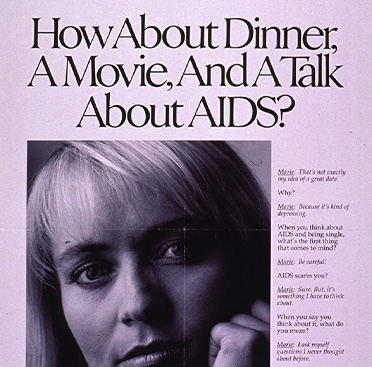

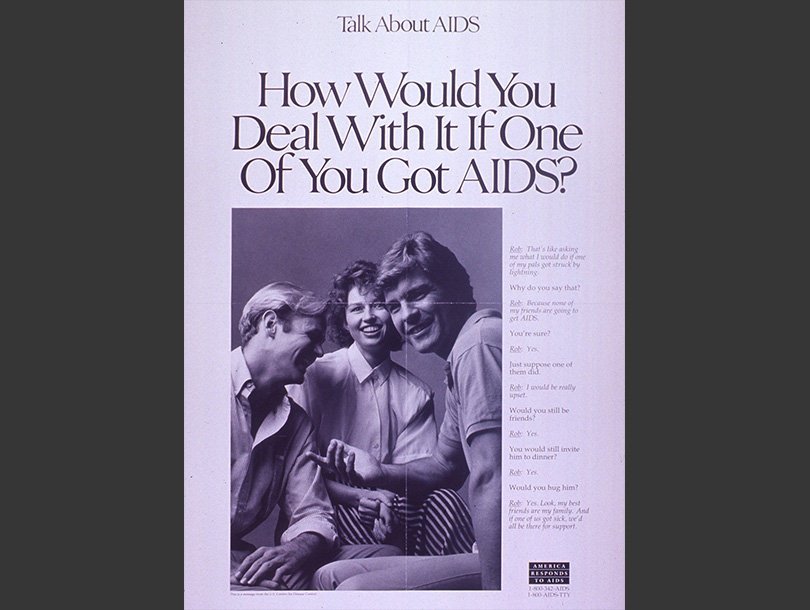

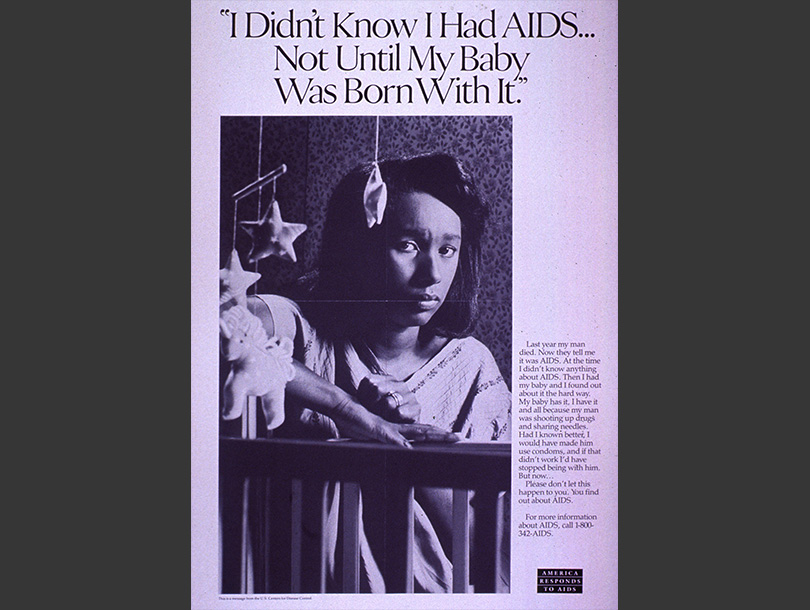

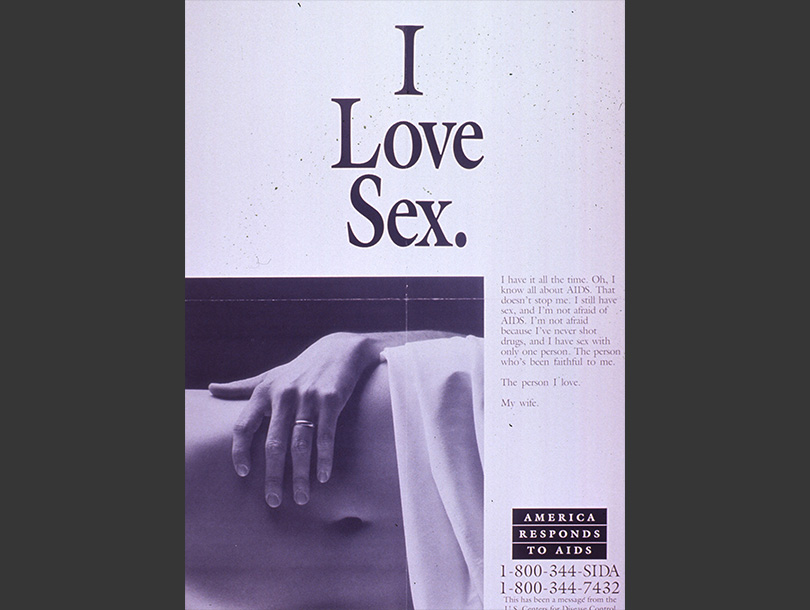

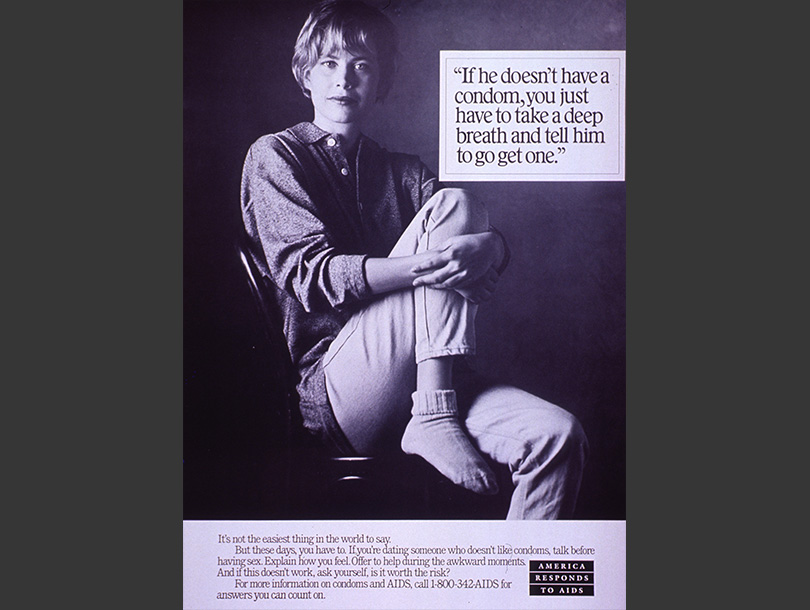

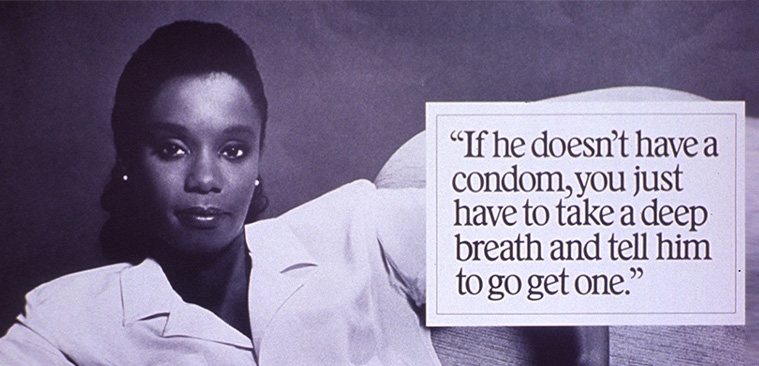

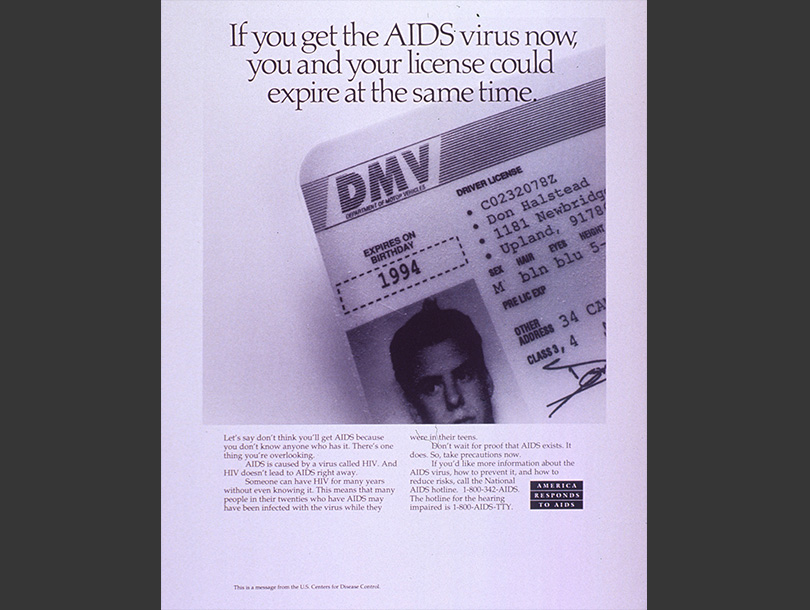

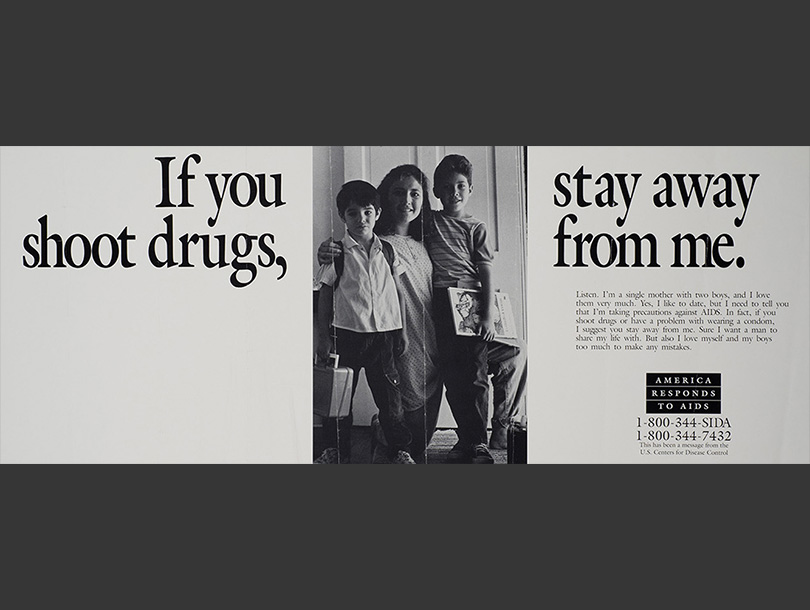

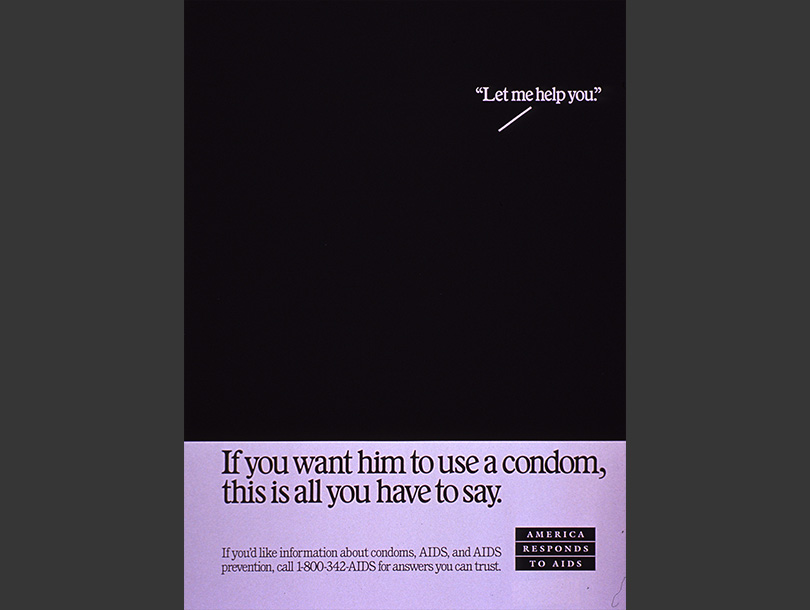

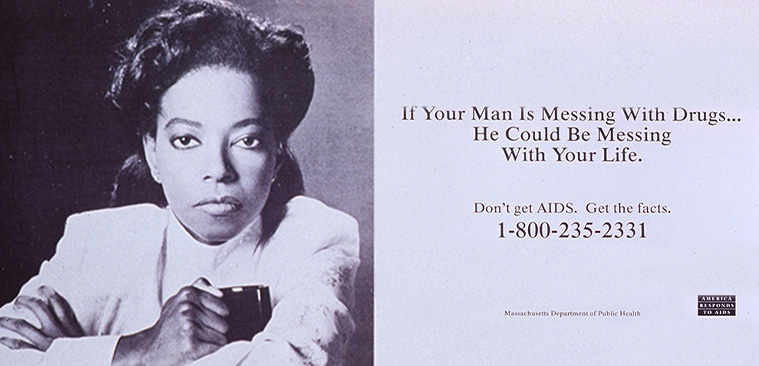

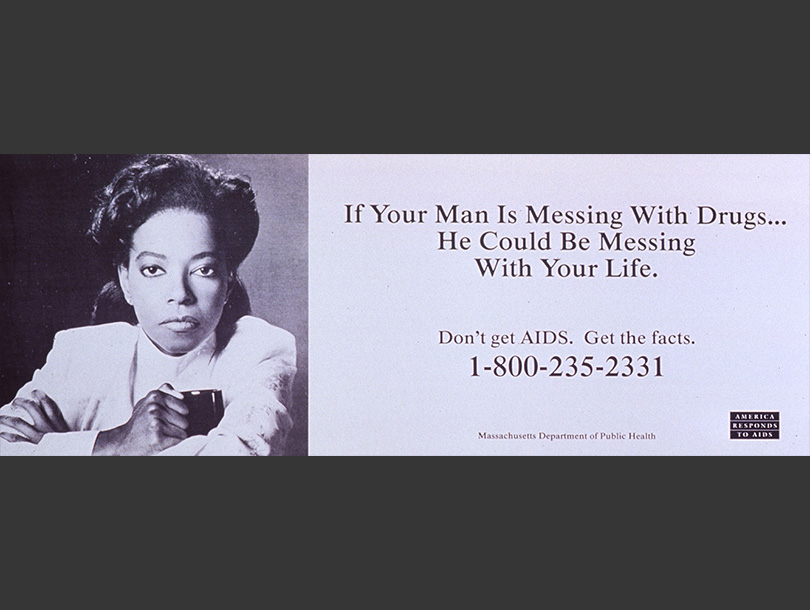

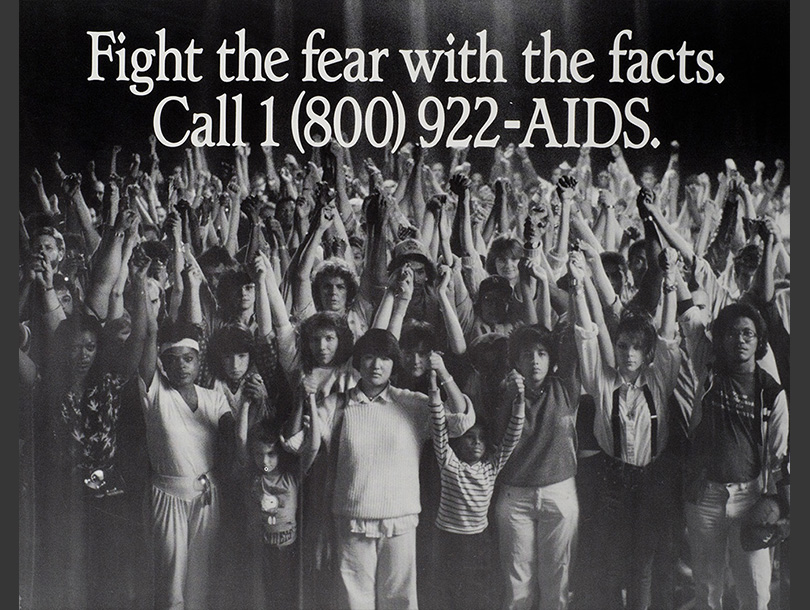

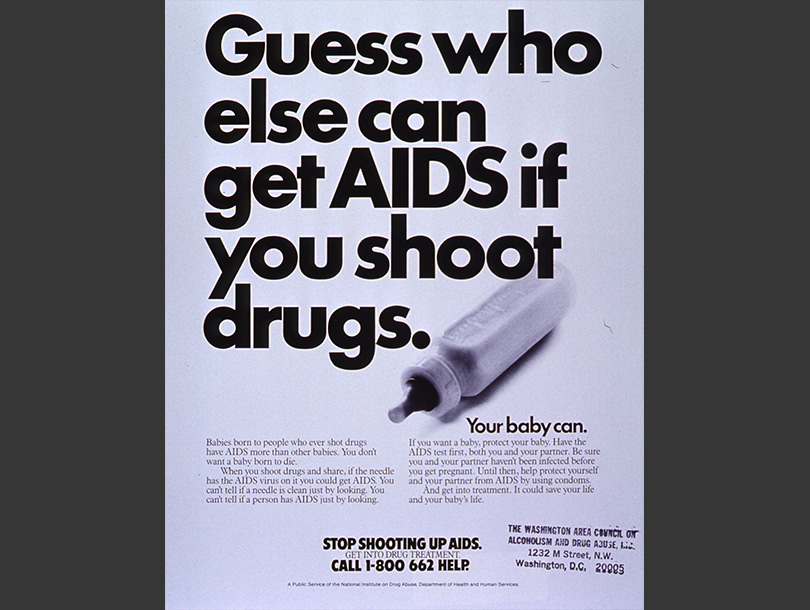

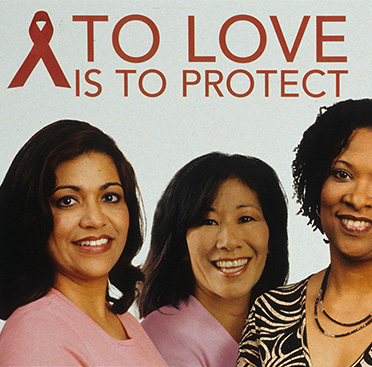

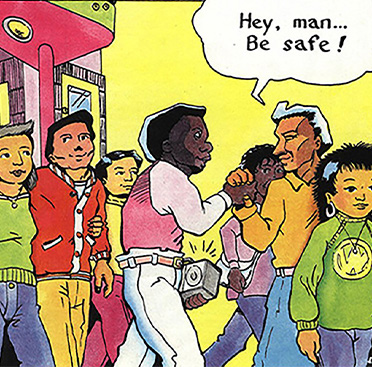

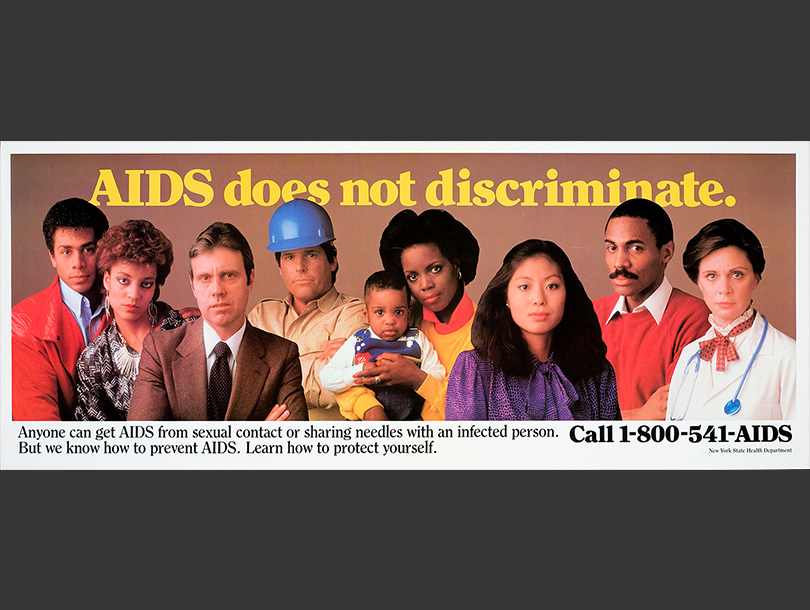

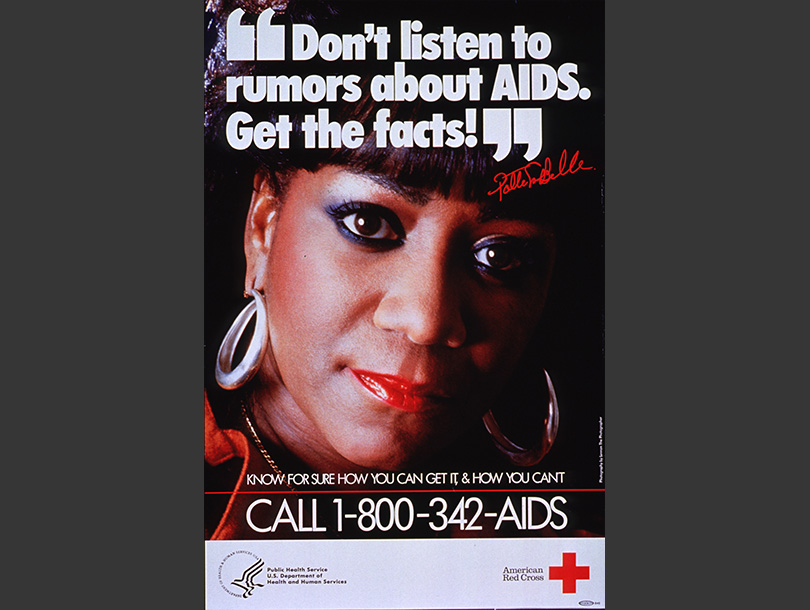

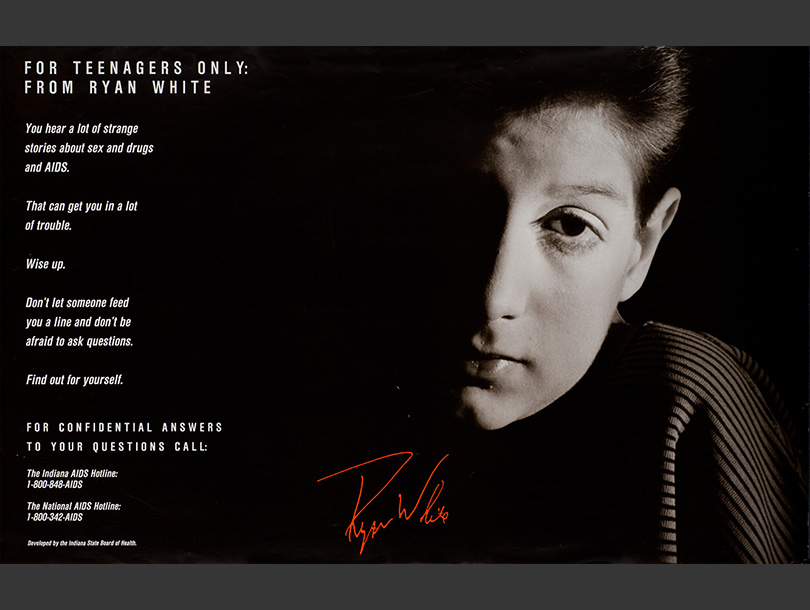

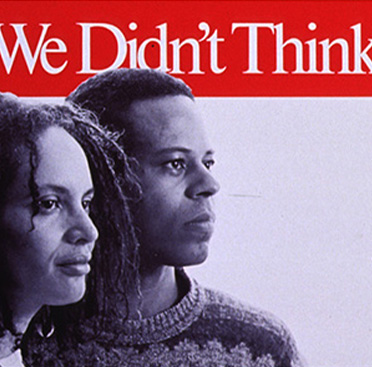

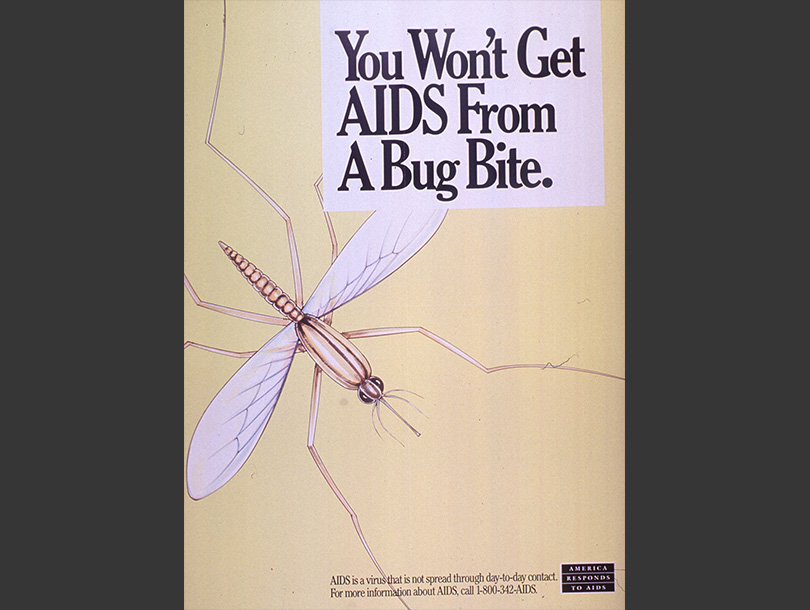

From 1987 to 1996, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sponsored America Responds to AIDS, a multipart public awareness campaign that focused on reaching a wide range of audiences variously defined by identity or behavior, from heterosexual single mothers, to teenagers of all races, to young adult African Americans, to people who lived in rural areas. The campaign reached millions, becoming a central prong in the “everyone is at risk” strategy of AIDS prevention. It suggested that the best way to respond to HIV/AIDS was to engage in honest conversations about risk behaviors, including the potential consequences of multiple partners, unprotected sex, intravenous drug use, or any activities that compromised the ability to make a sound, safe judgment. Not all applauded the effort. Some, particularly service providers working with groups with a high incidence of HIV/AIDS, most notably young men who had sex with men and intravenous drug users, saw the campaign as ignoring the particular needs of these communities in favor of supporting low-risk individuals. While these efforts claimed to reach all Americans, the efforts did not provide necessary outreach and education to those who also needed it.

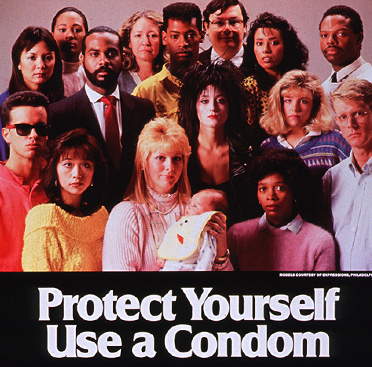

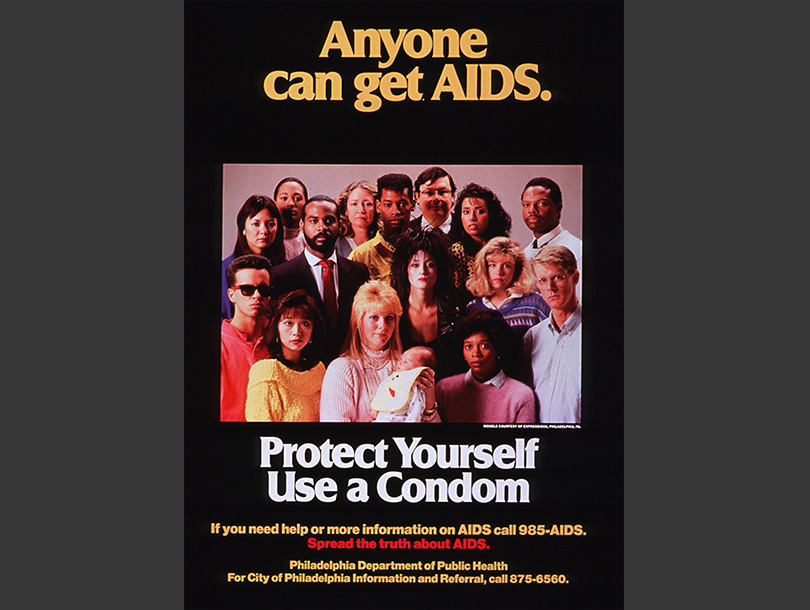

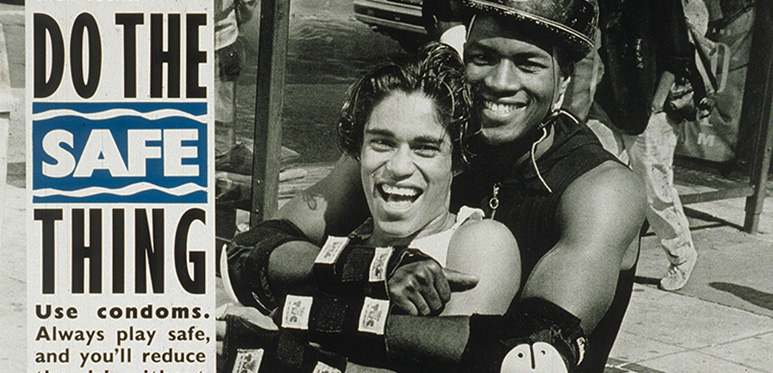

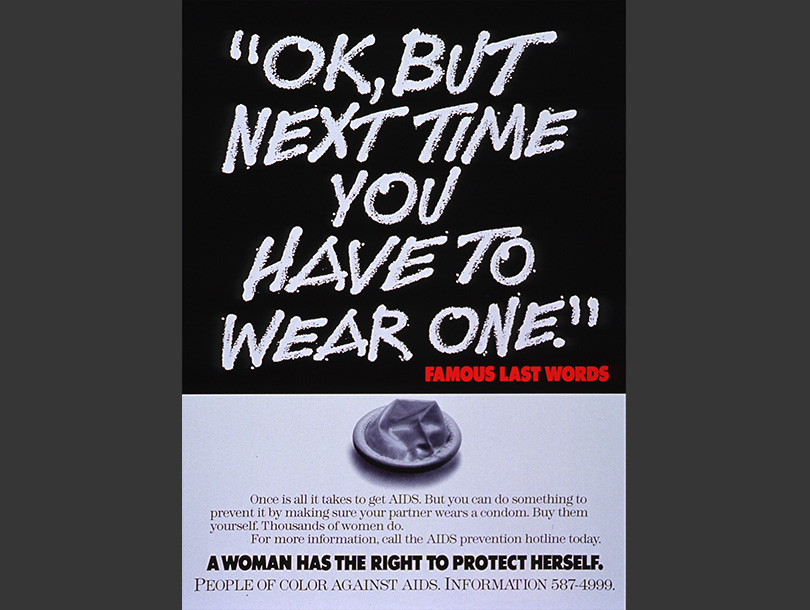

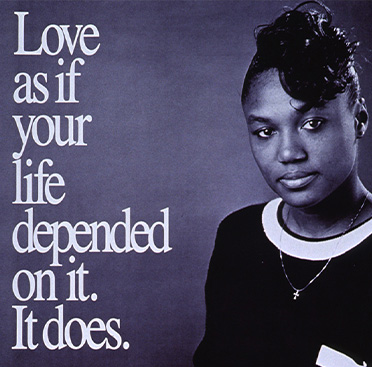

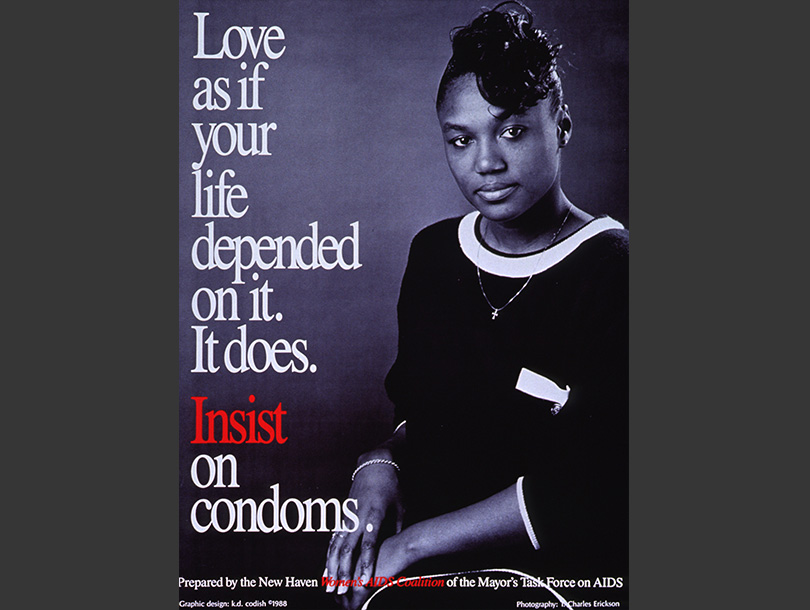

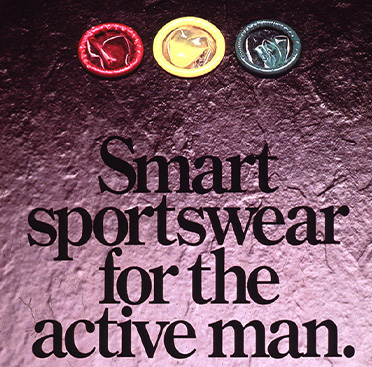

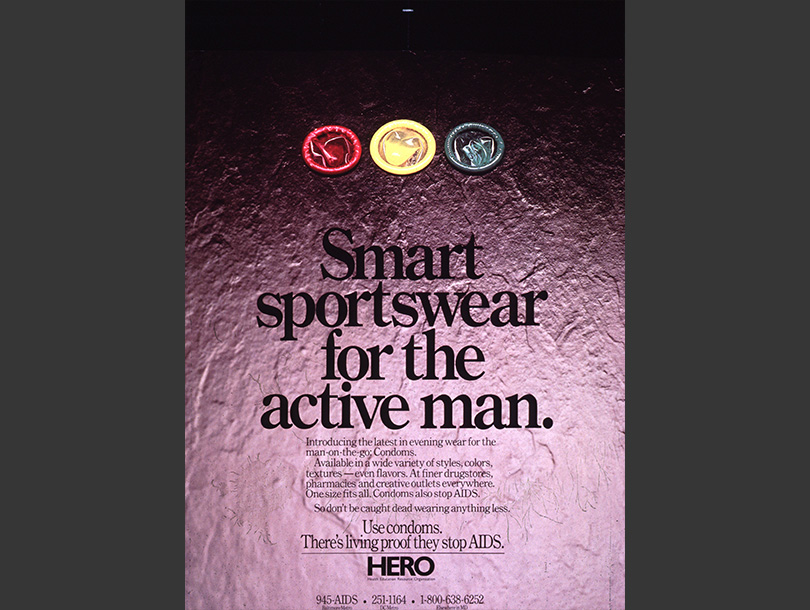

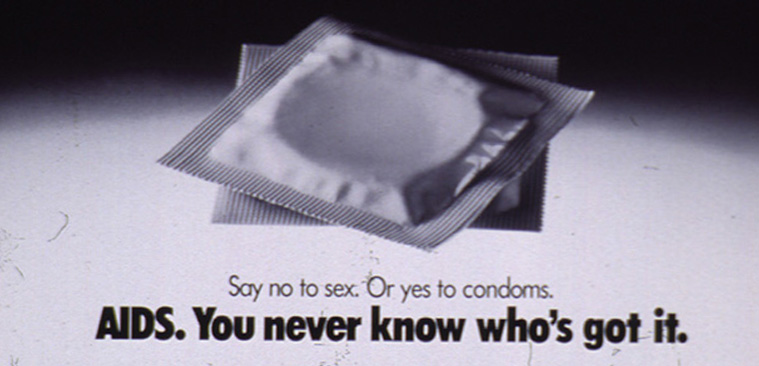

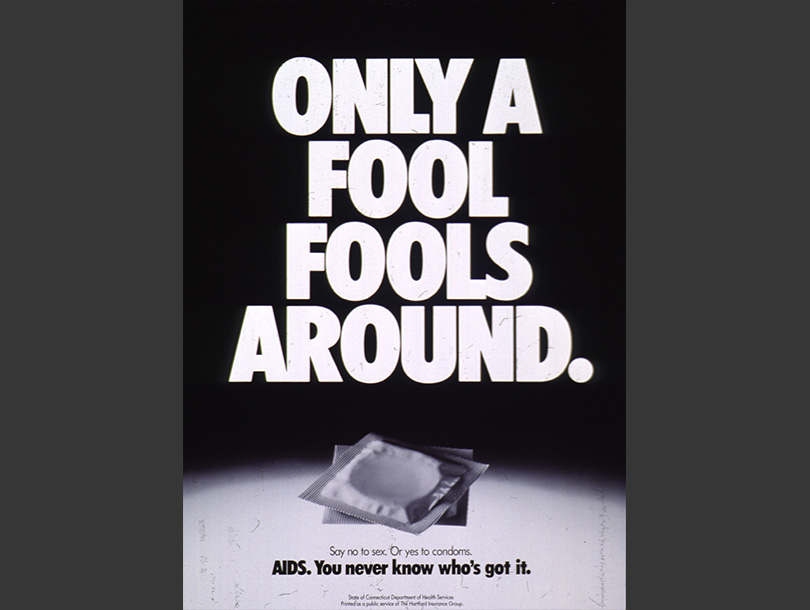

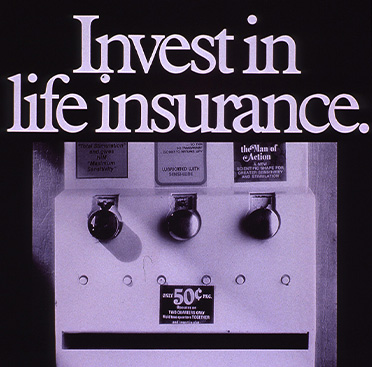

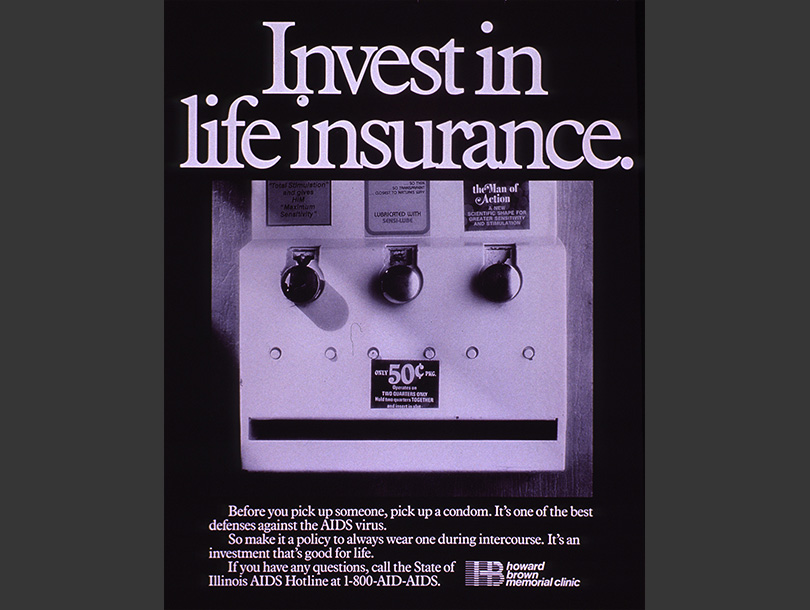

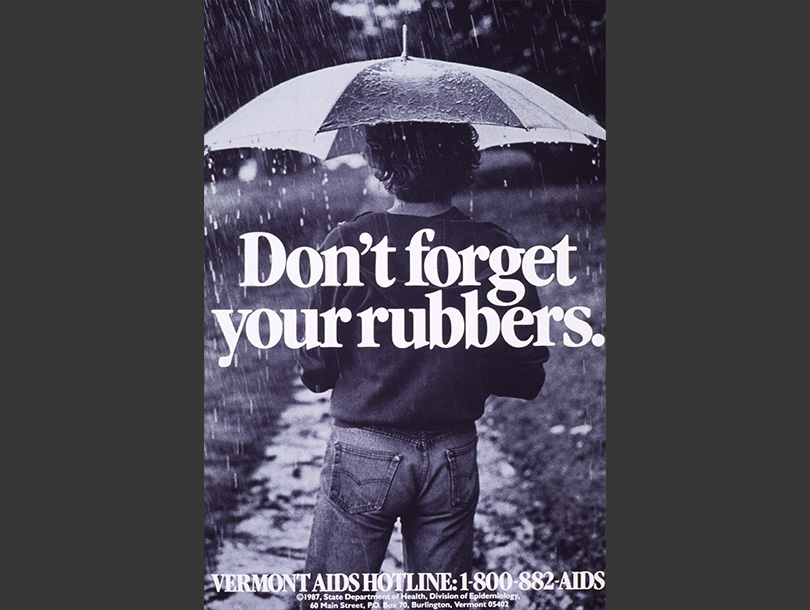

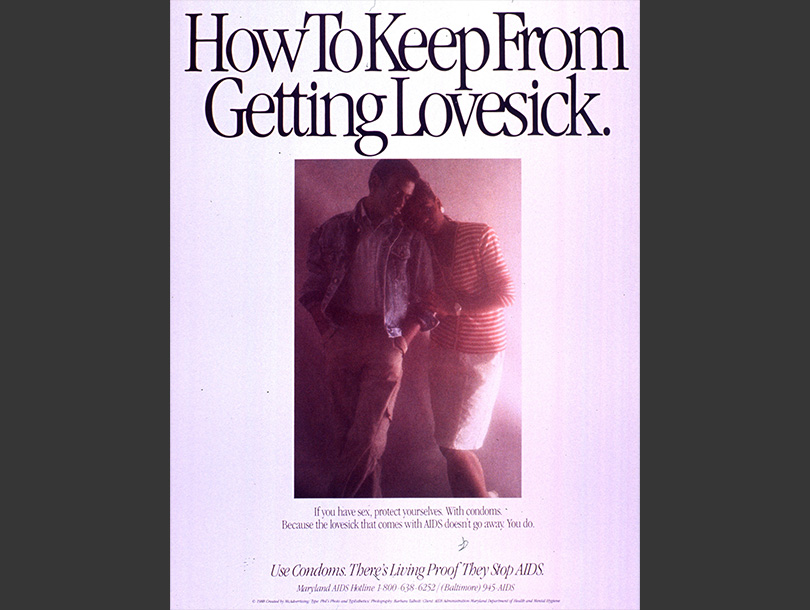

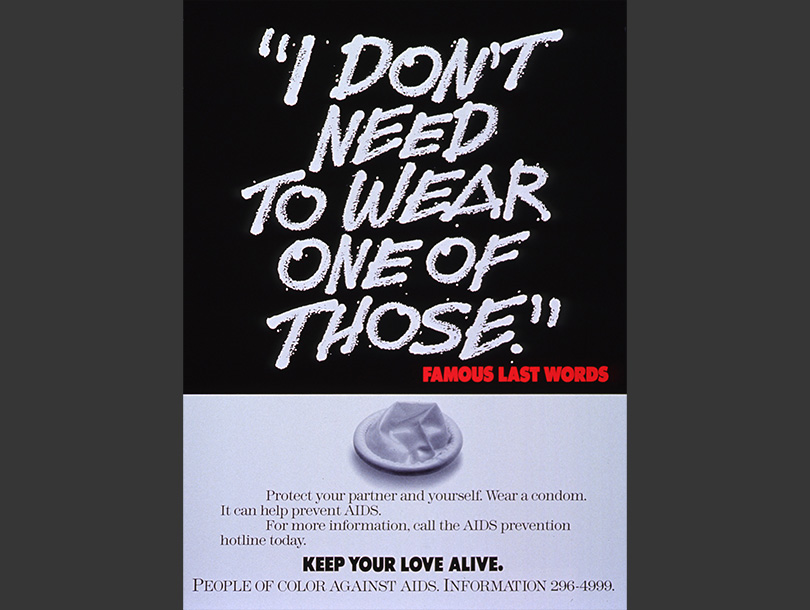

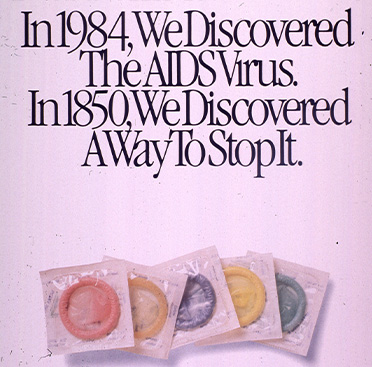

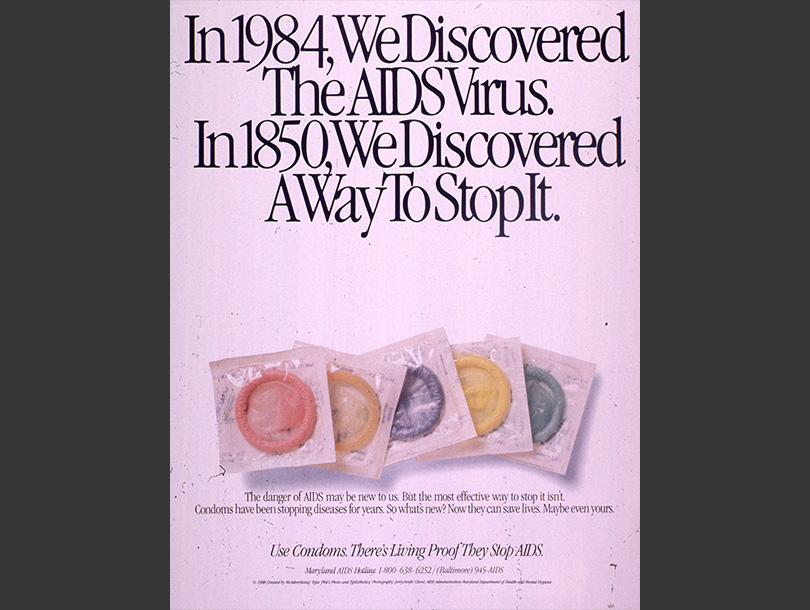

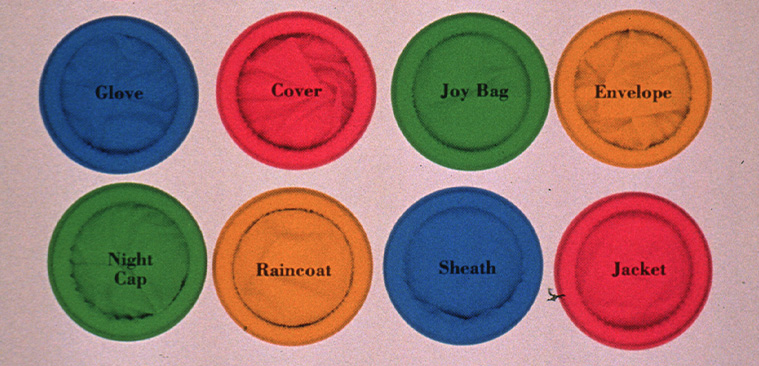

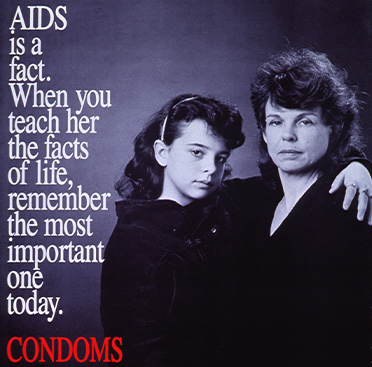

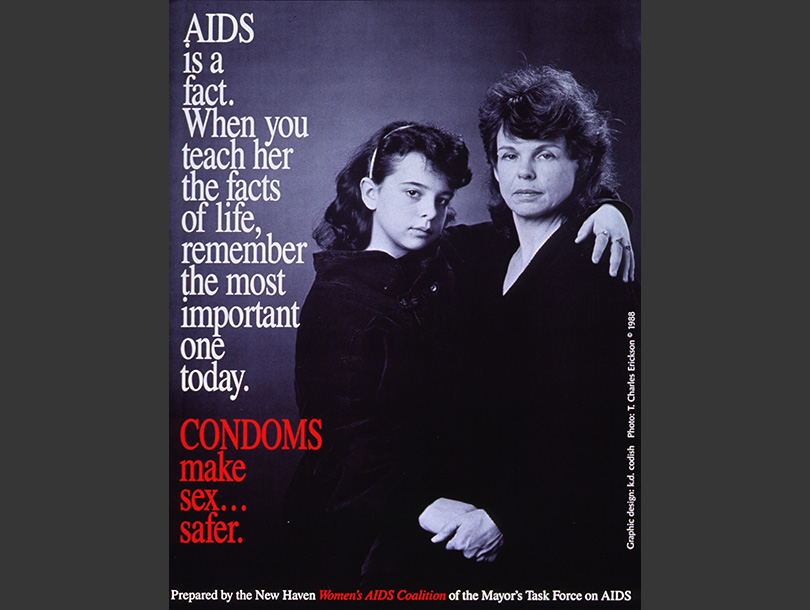

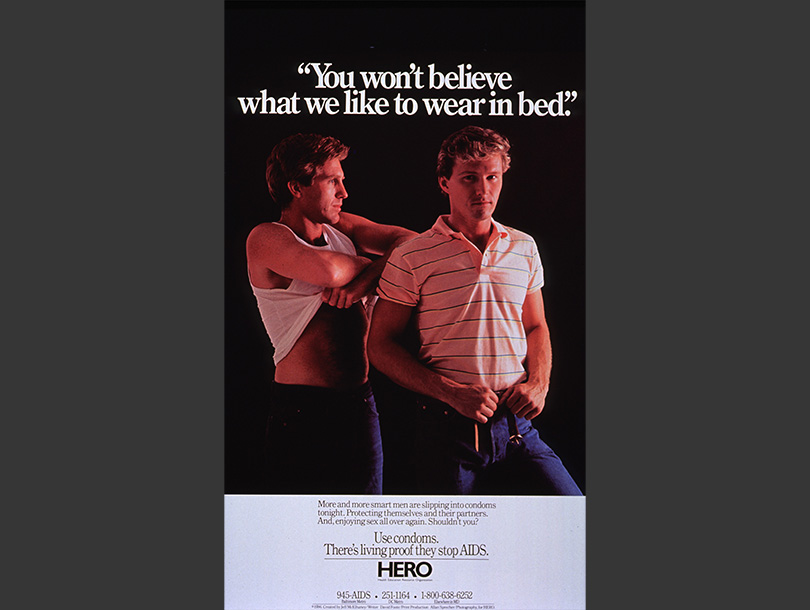

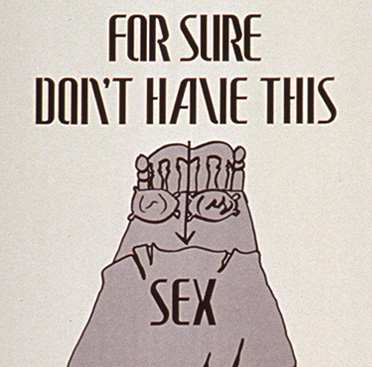

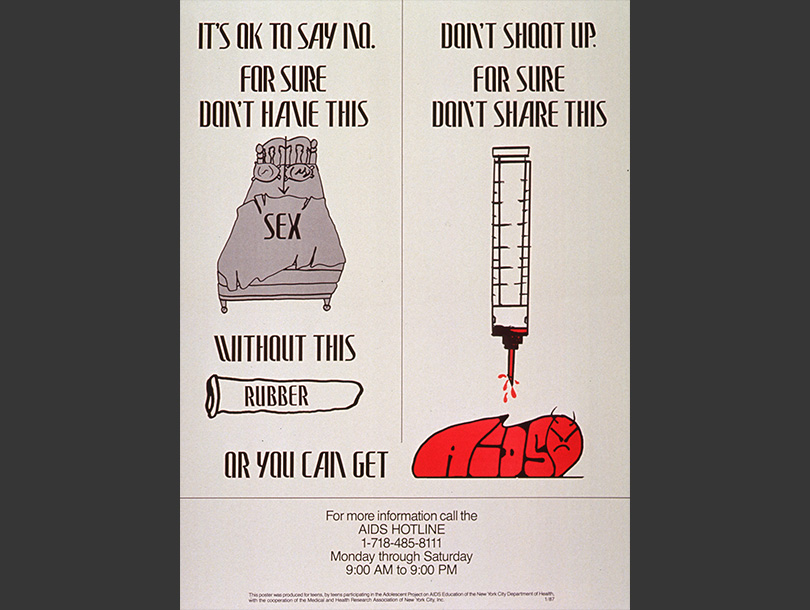

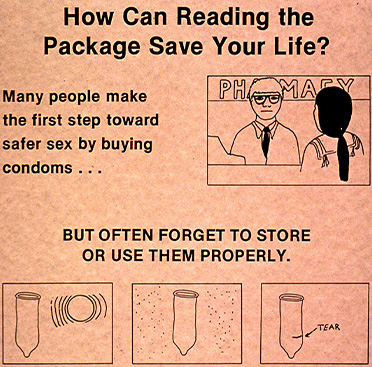

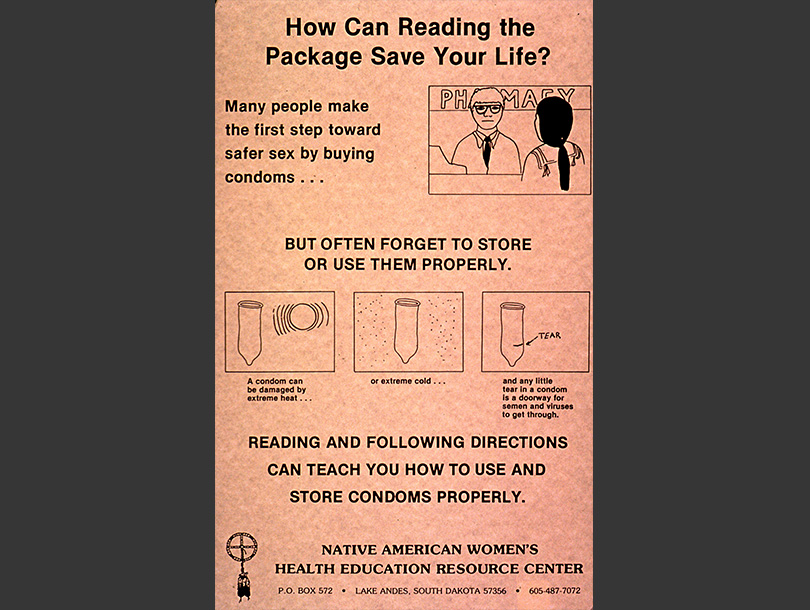

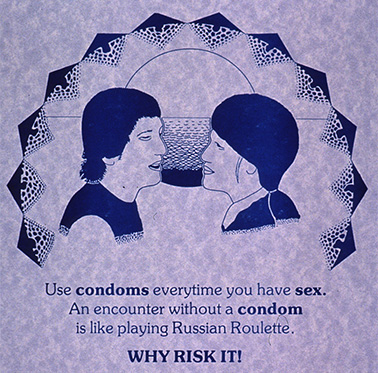

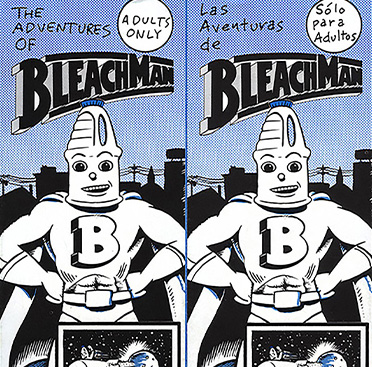

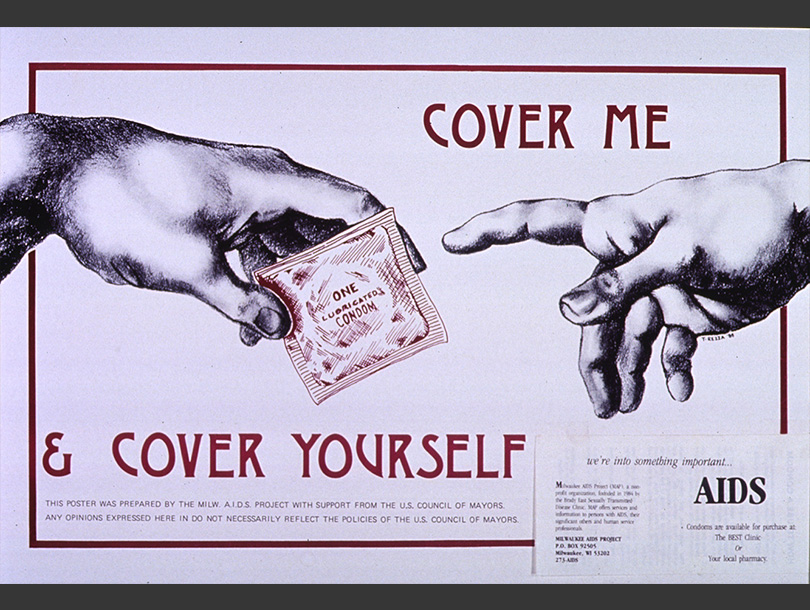

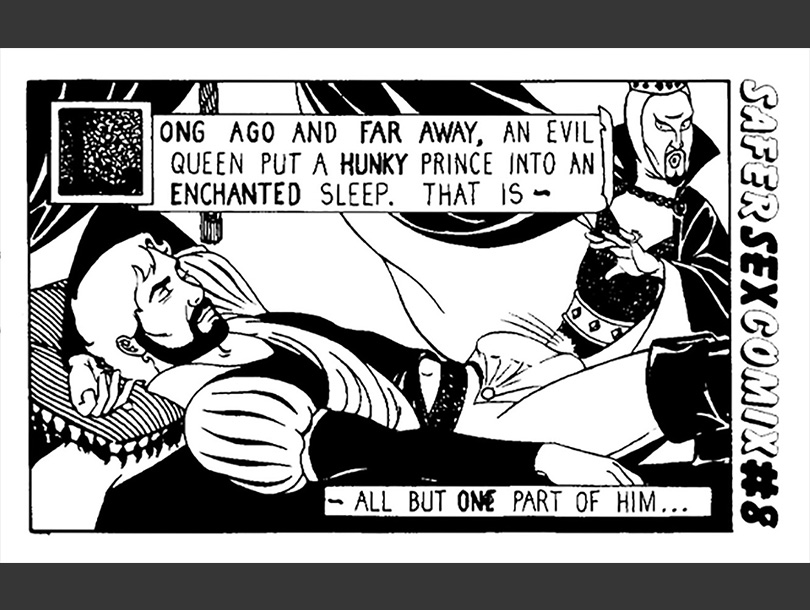

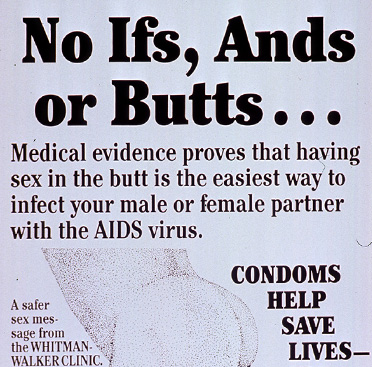

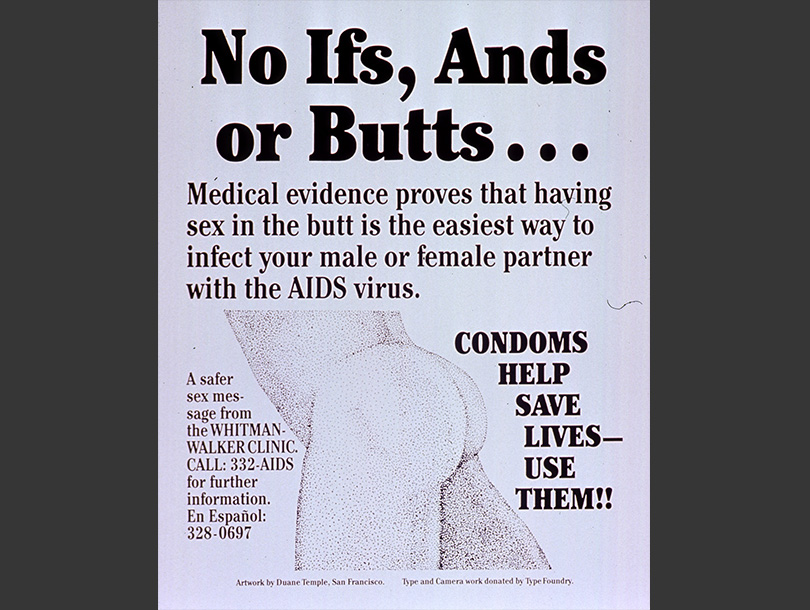

View images in this themeCondoms as Safer Sex

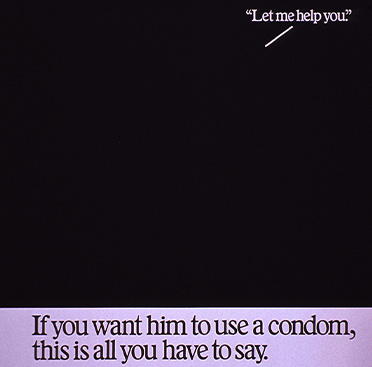

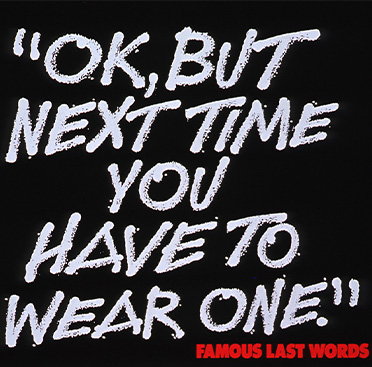

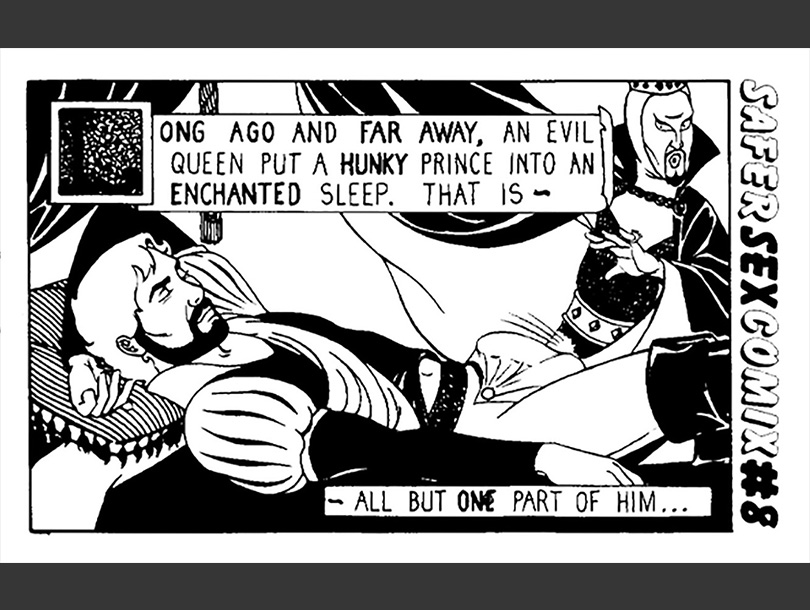

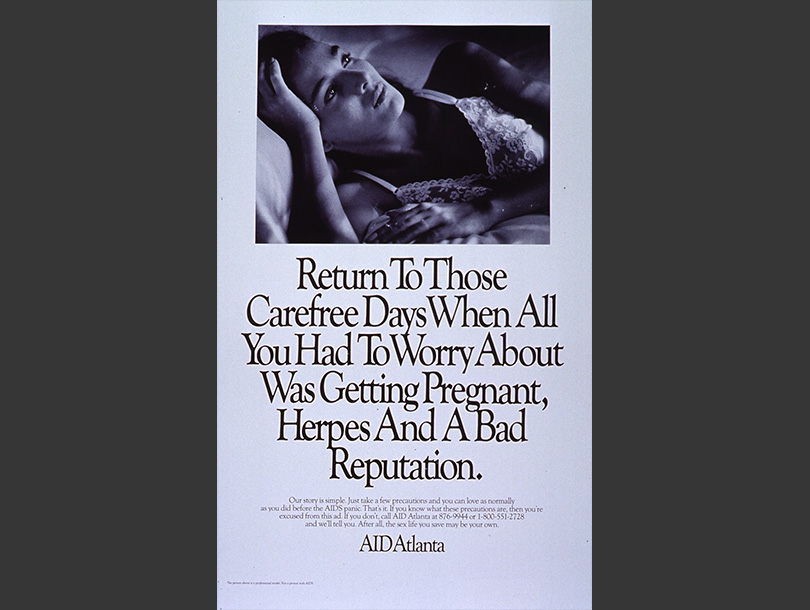

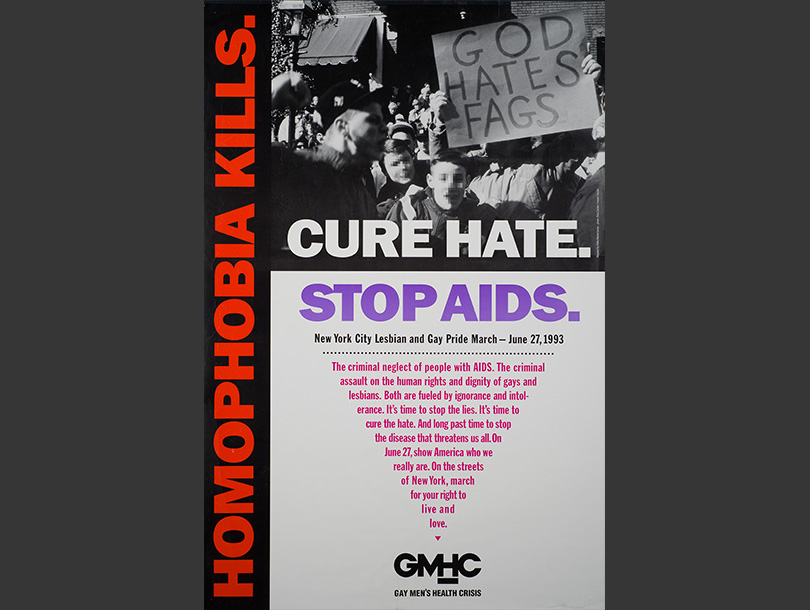

In 1985, researchers at the University of California at San Francisco confirmed what many AIDS service providers and people with AIDS already assumed: condoms, when used consistently and correctly, could prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS. This was true with sex between men as well as sex between men and women. These findings, with support from the Office of the Surgeon General of the United States pushed public health departments across the country to create social marketing campaigns to encourage condom use. Some campaigns were graphically subdued, using large type and funny copy to entice a largely heterosexual audience without seeming illicit. Alternatively, the Safer Sex Comix published by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York City used humorous, explicit imagery to reach gay audiences by suggesting that condom use could be pleasurable.

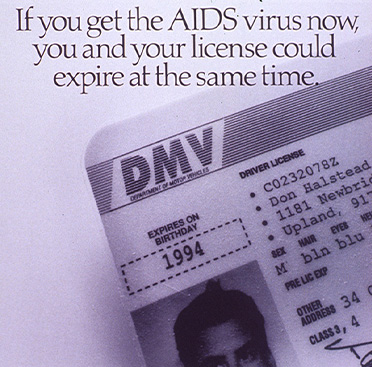

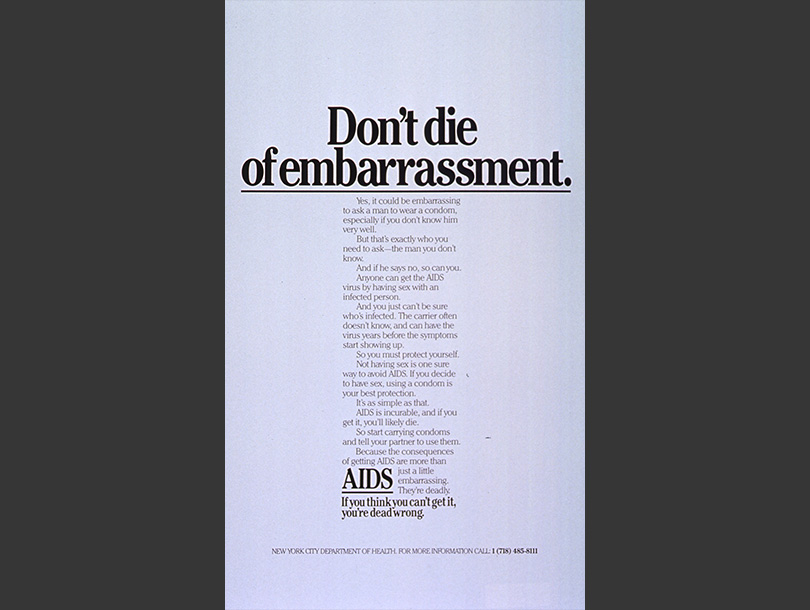

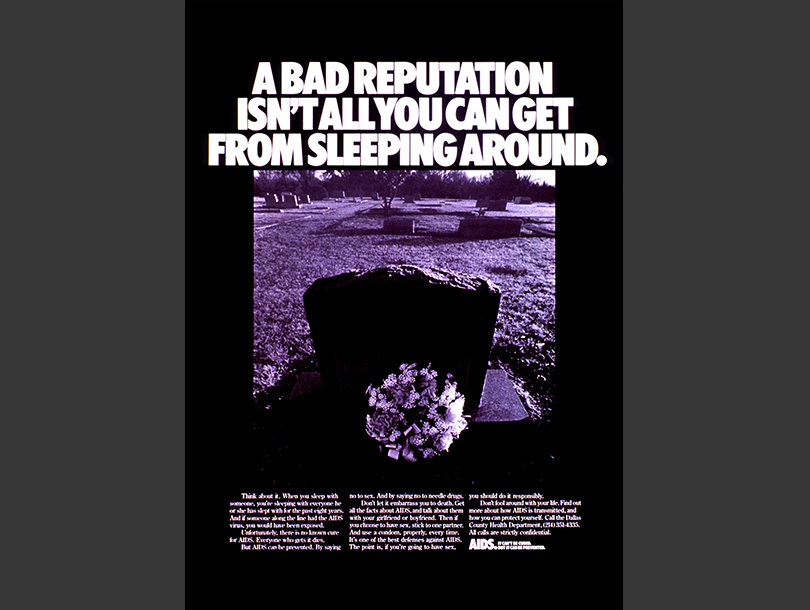

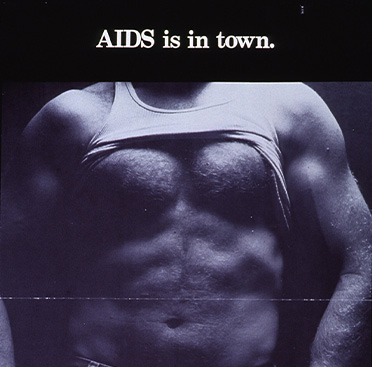

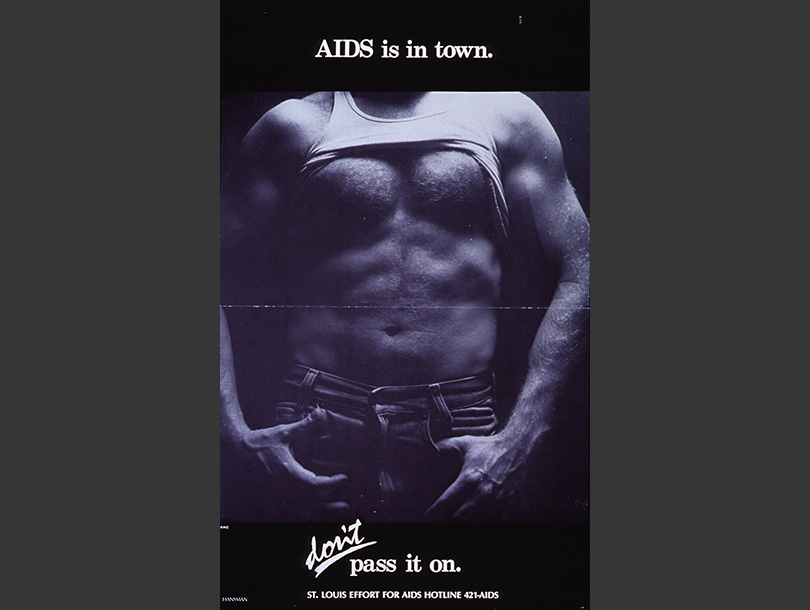

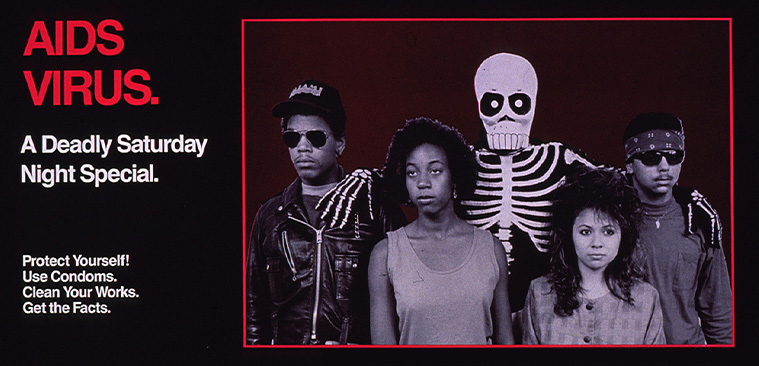

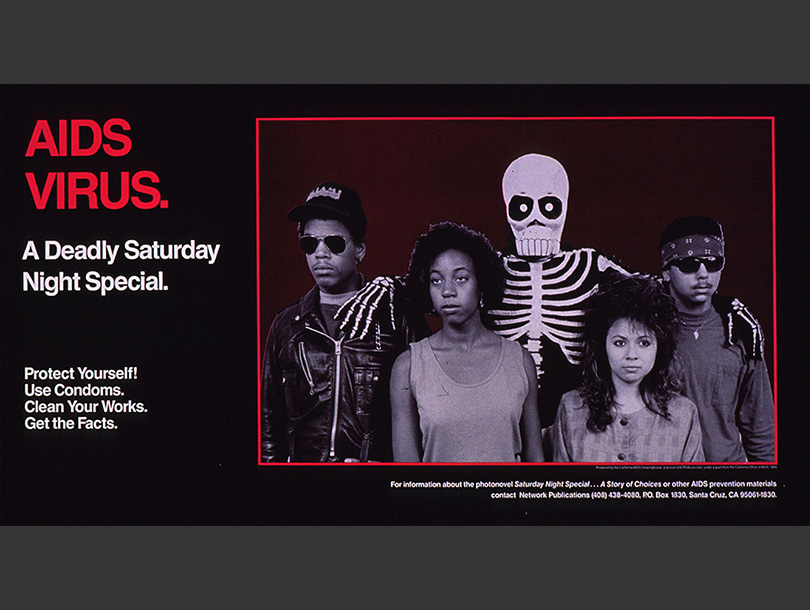

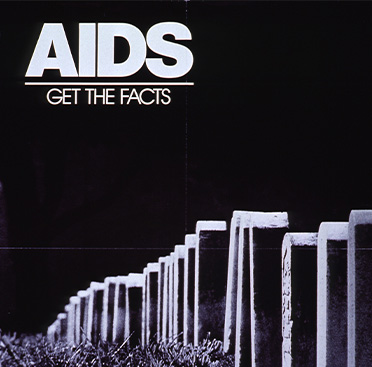

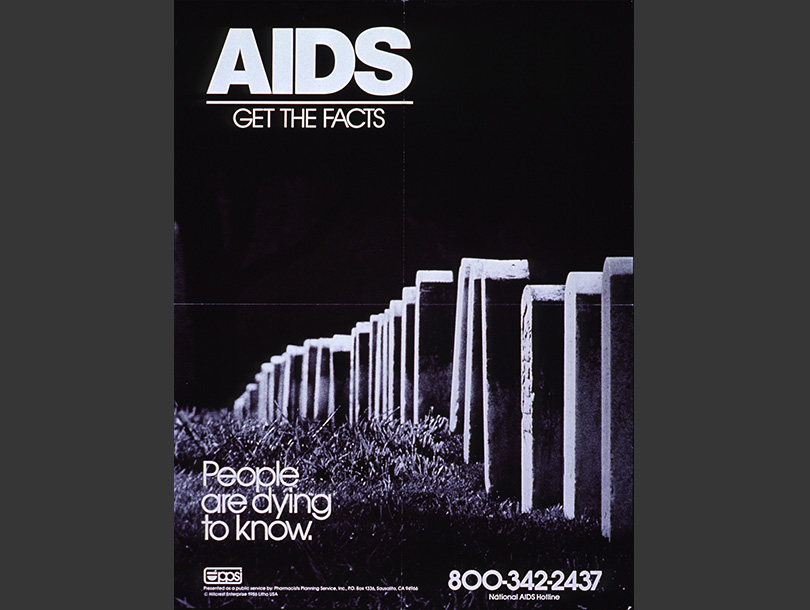

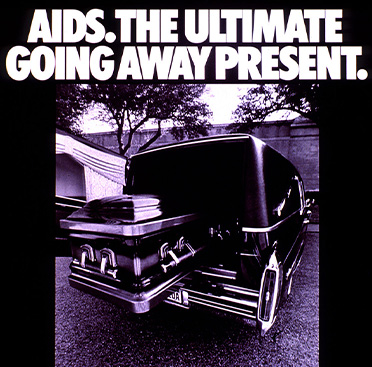

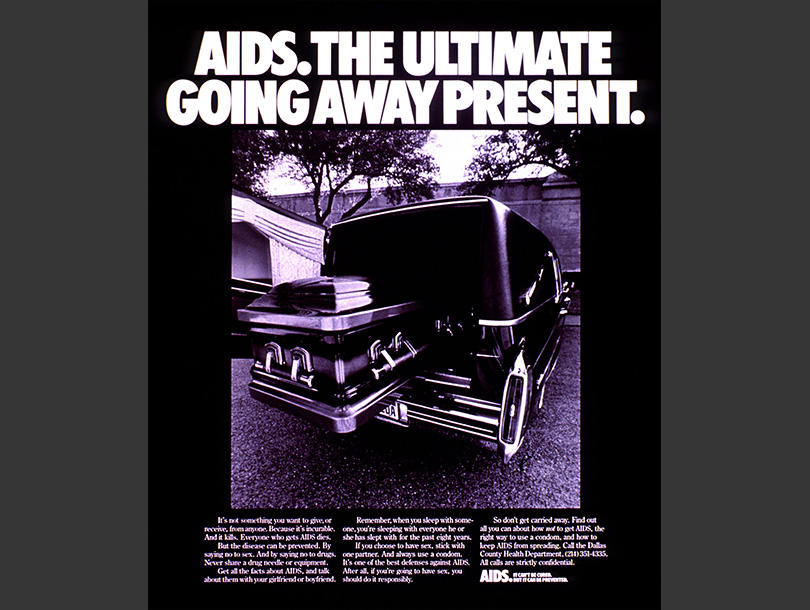

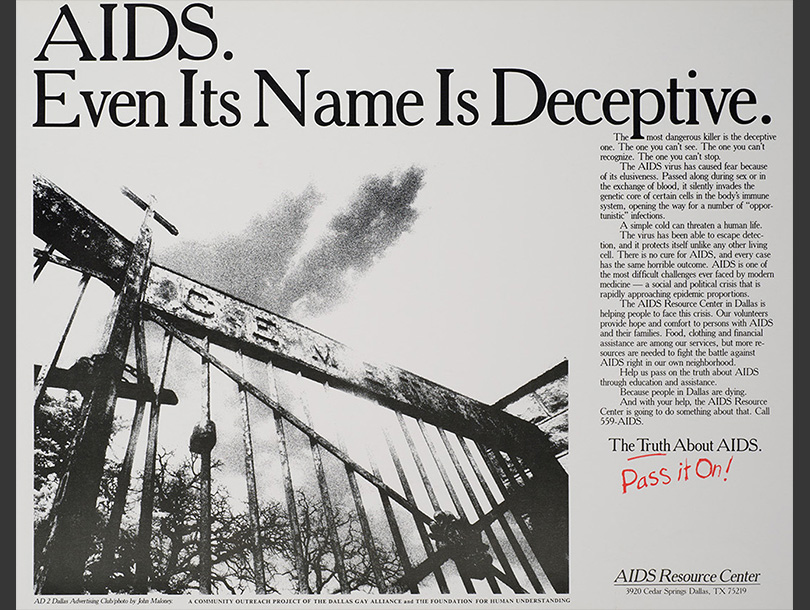

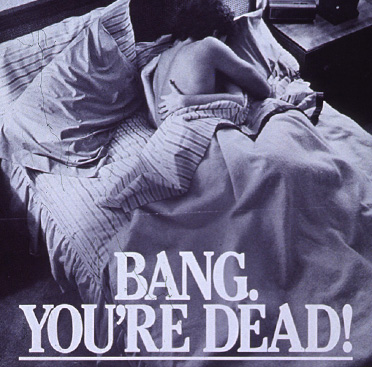

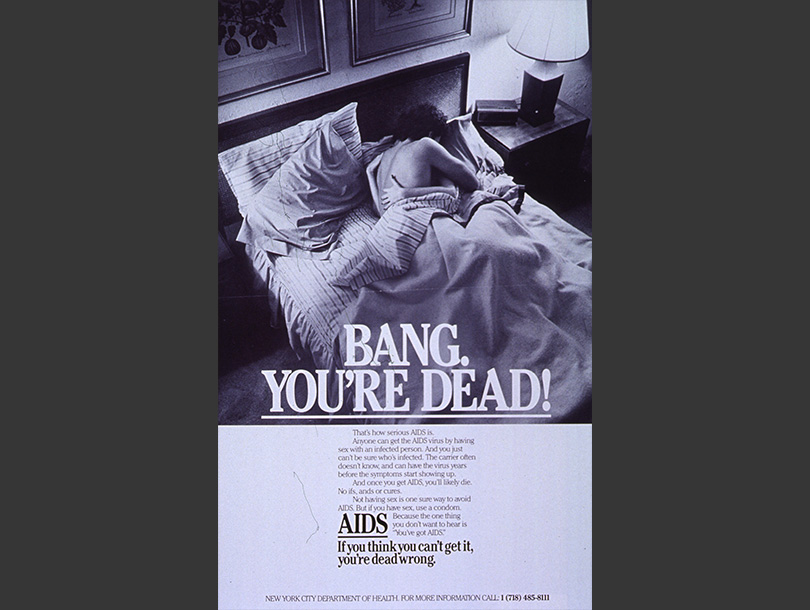

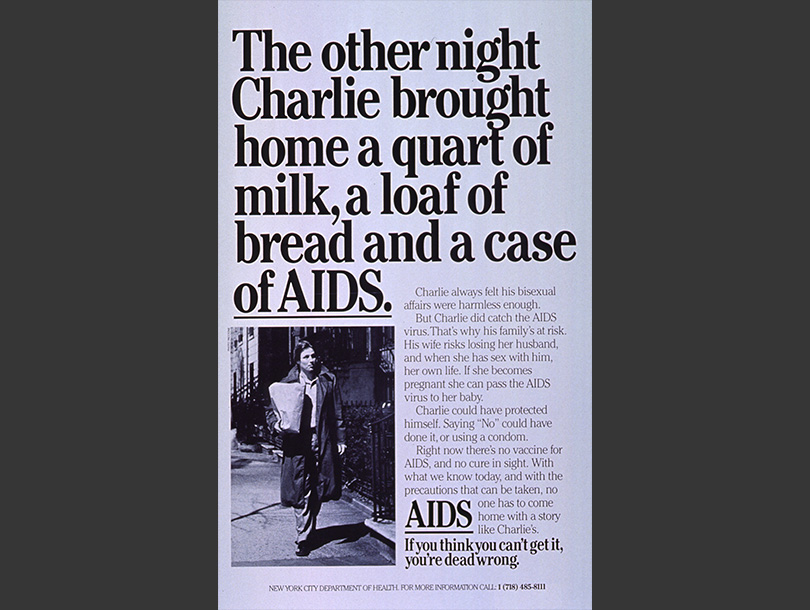

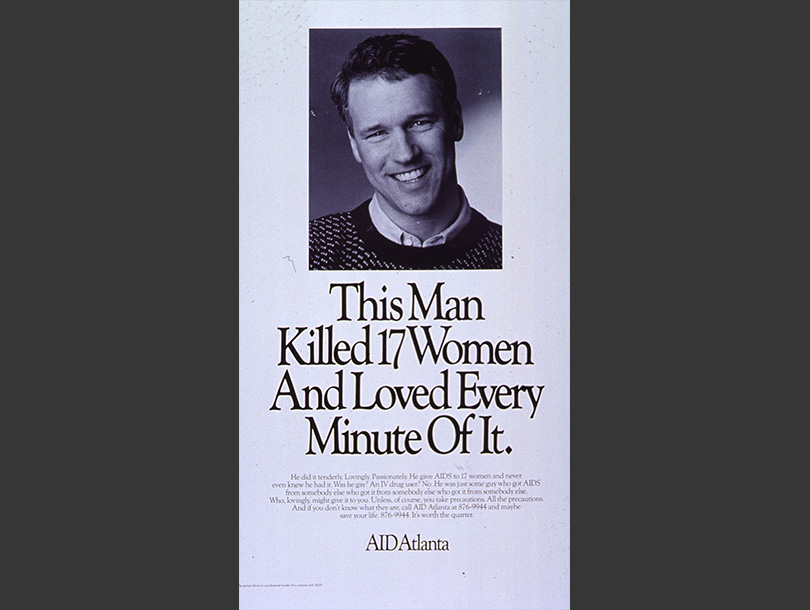

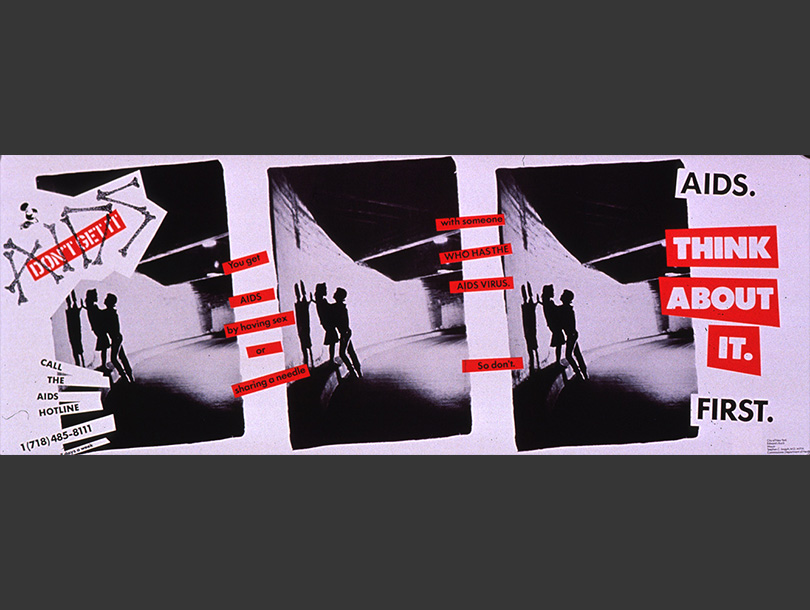

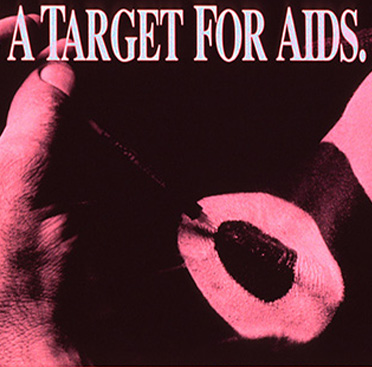

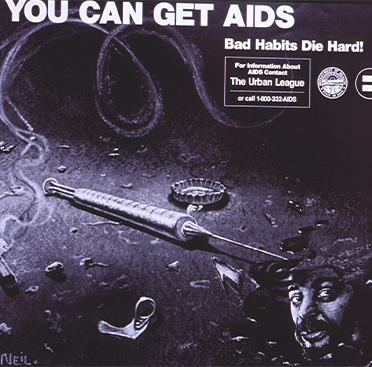

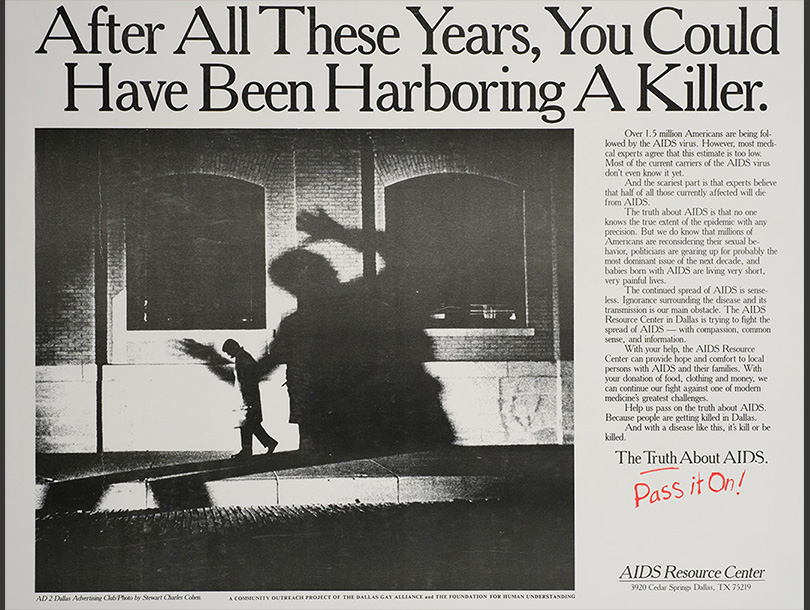

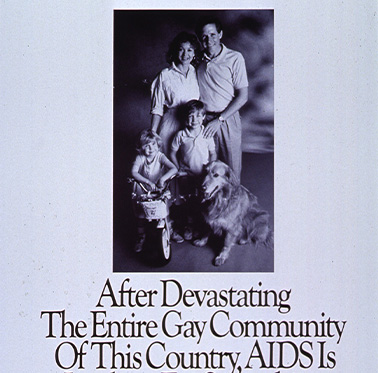

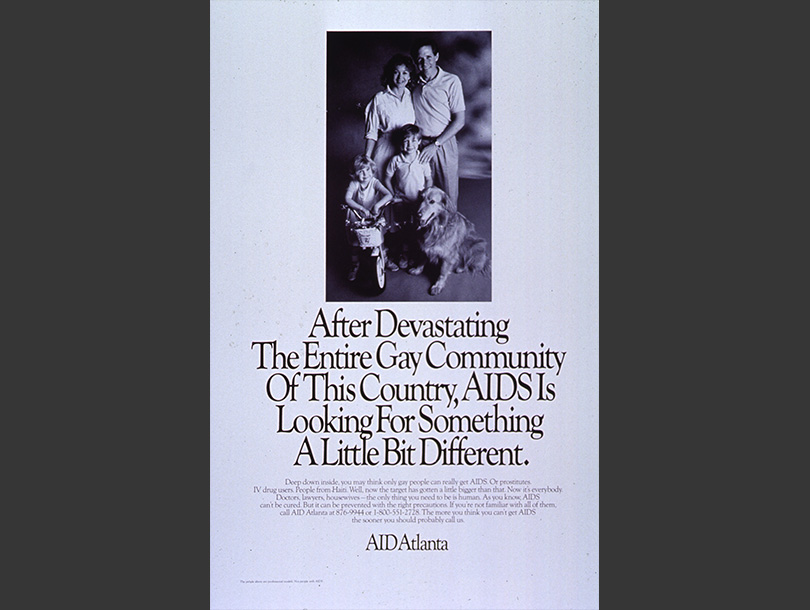

View images in this themeFear Mongering

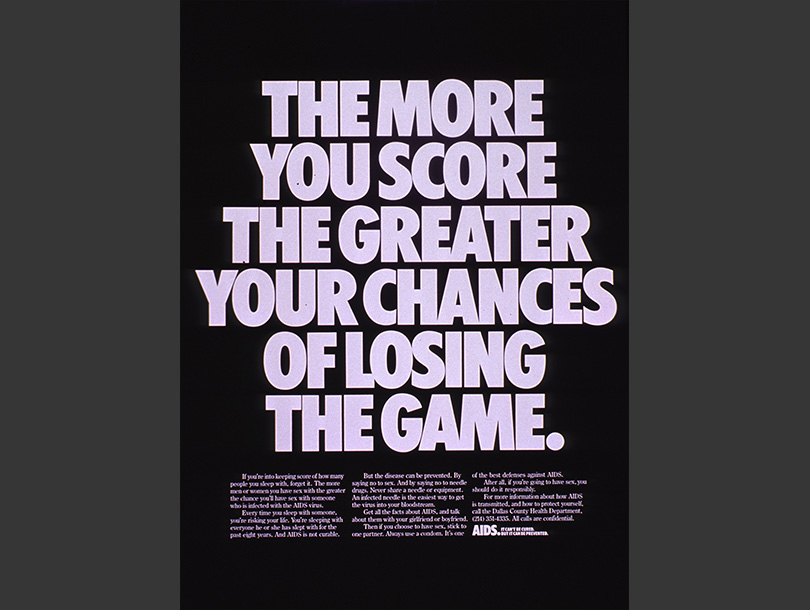

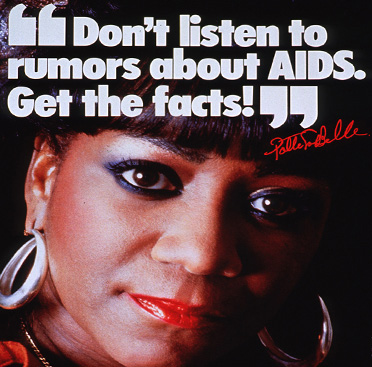

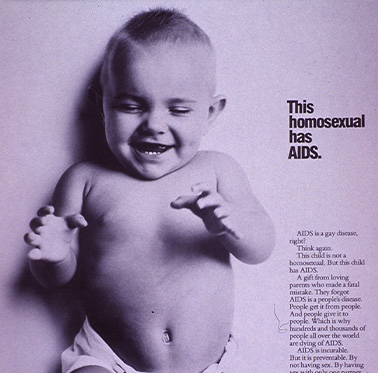

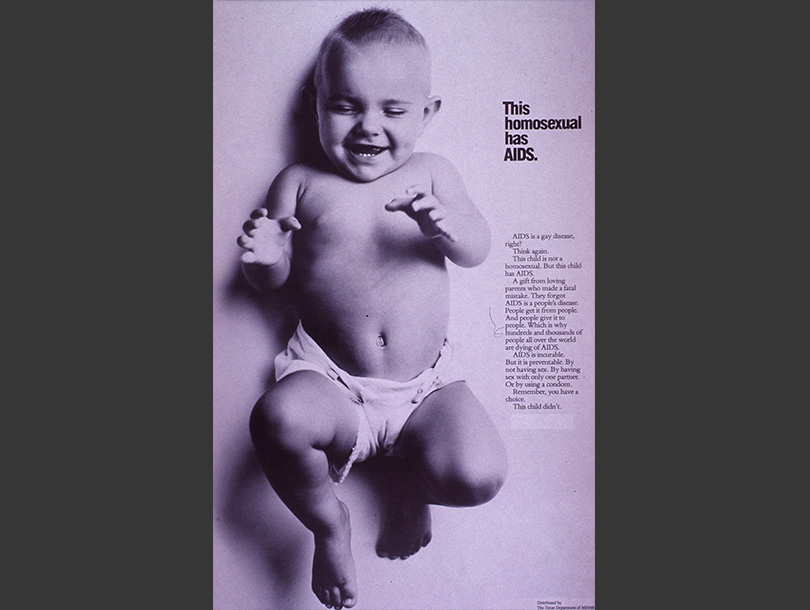

As AIDS became a more widespread concern, public health officials and government agencies felt an increasingly urgent need to encourage people to protect themselves and their partners. Many state and local AIDS organizations tried to exert pressure on audiences using fear to prompt behavioral change, particularly among White heterosexuals who did not consider themselves at risk. Designed as an alternative to safer-sex campaigns, which highlighted pleasure and encouraged readers to rethink sexual practices in the age of AIDS, these advertisements shared a common visual and verbal language of gruesome death without providing information about how to prevent it. While a few emphasized the necessity of condom use or warned against sharing needles, most simply told readers to “get the facts” without providing substantive information. Often the fear came in an anti-sex form, such as, “Every time you sleep with someone, you’re risking your life.” In all cases, the campaigns harnessed fear to force people to acknowledge AIDS, but often omitted the helpful public health information about strategies citizens could use to protect themselves.

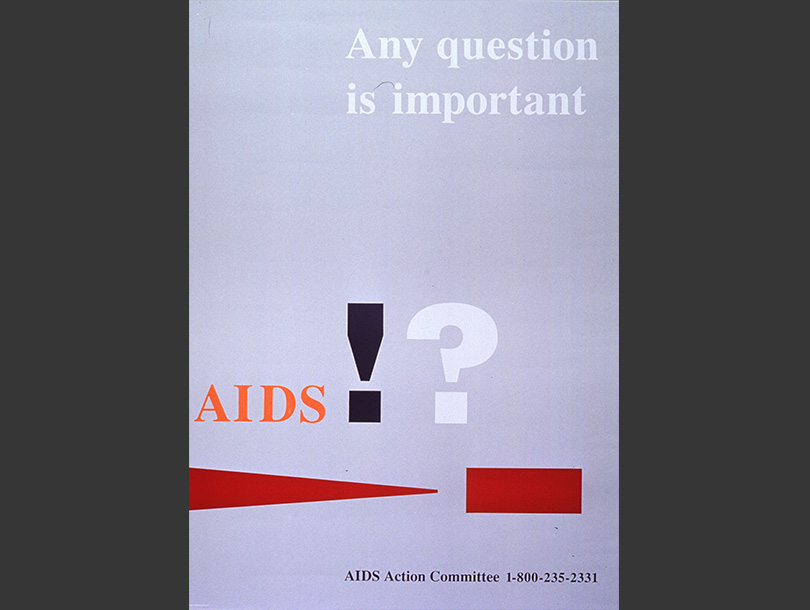

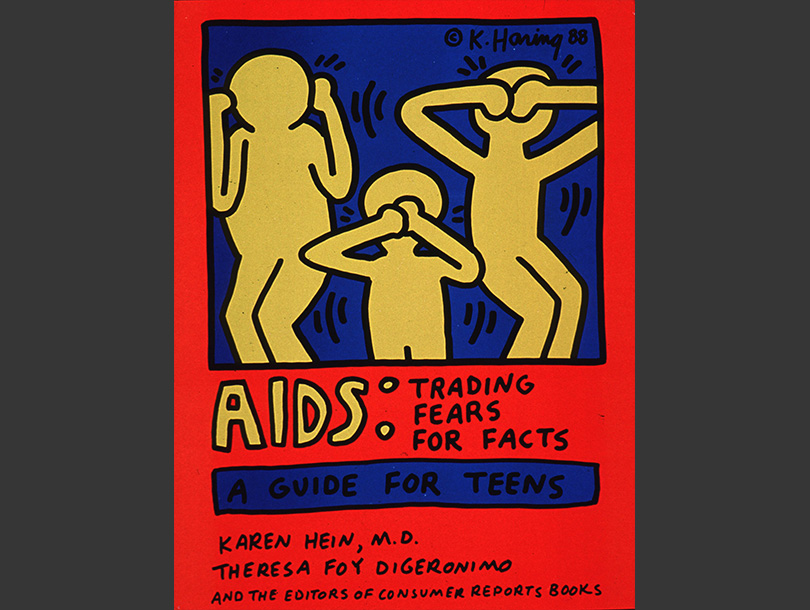

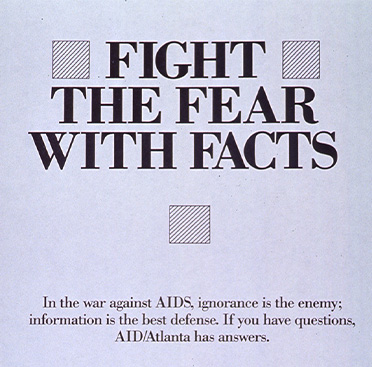

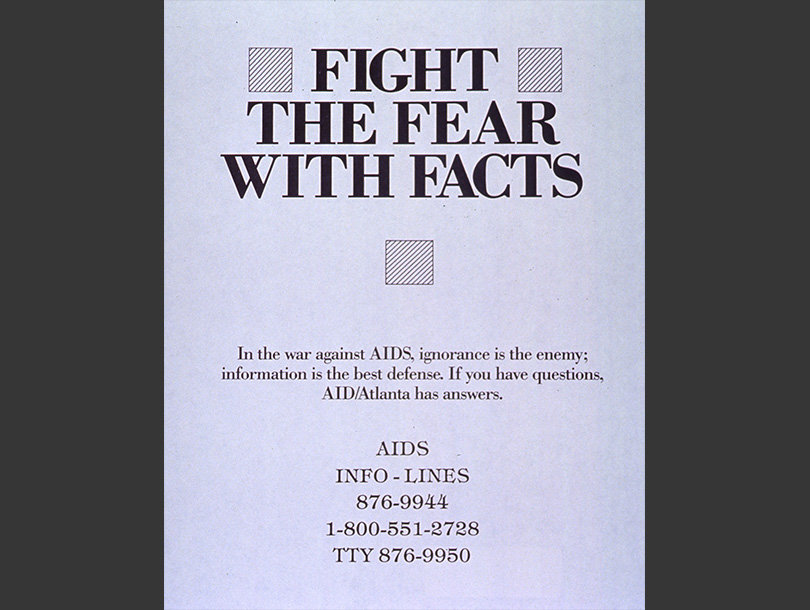

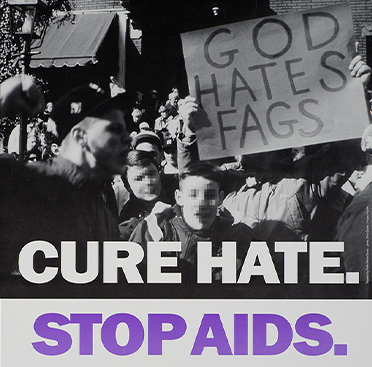

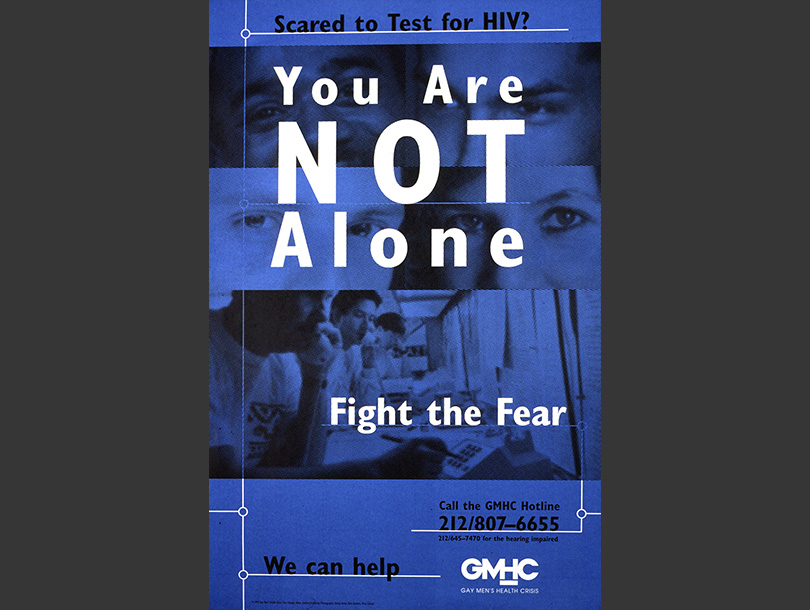

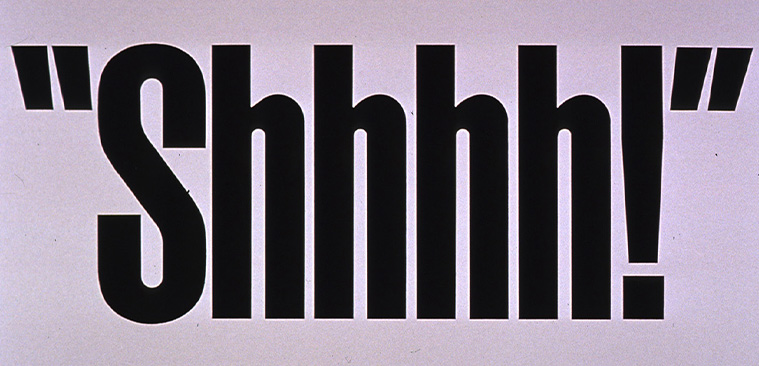

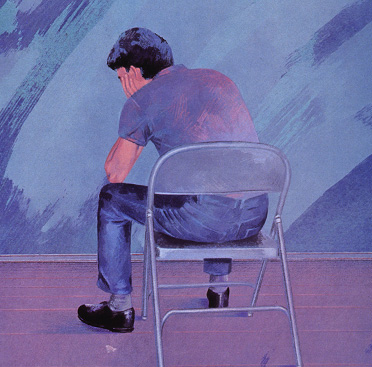

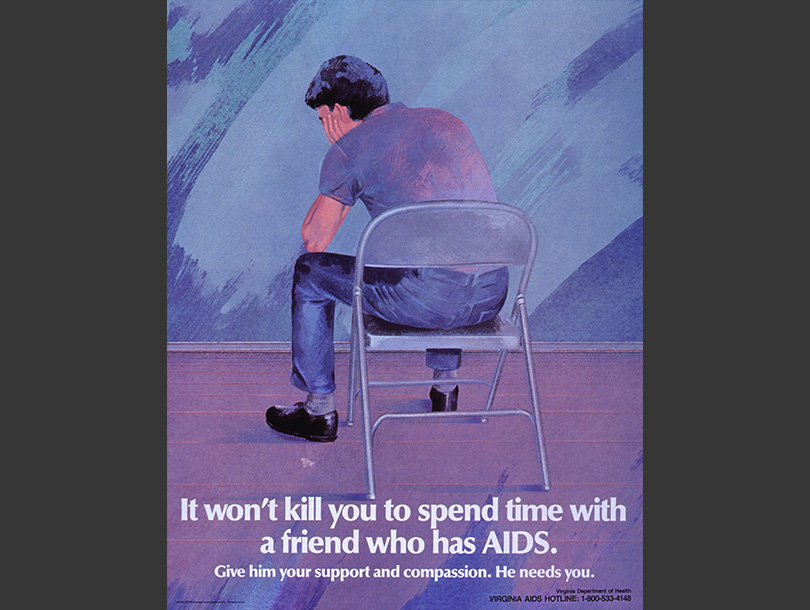

View images in this themeFight the Fear

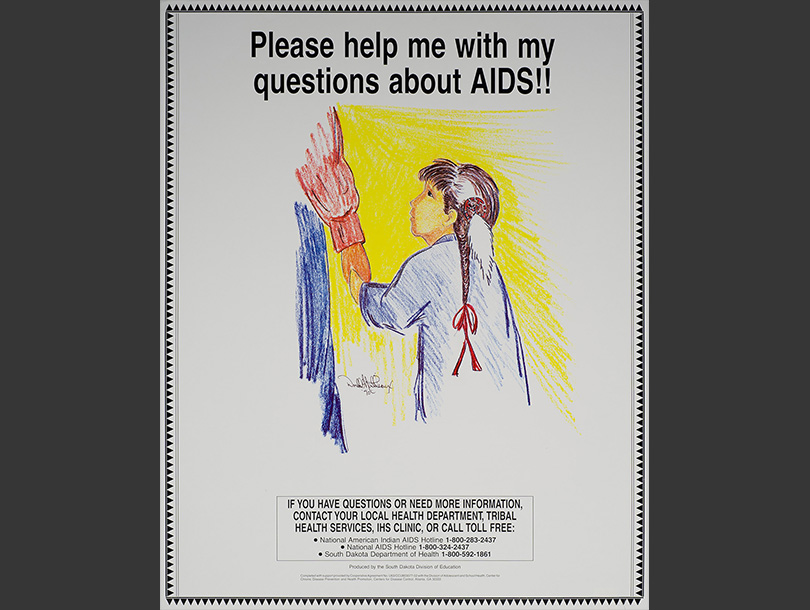

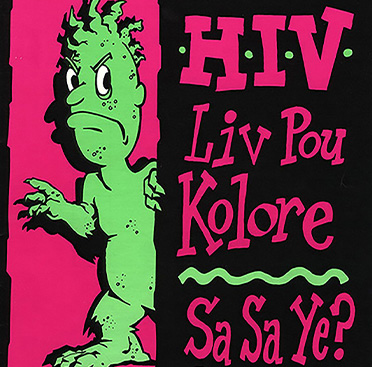

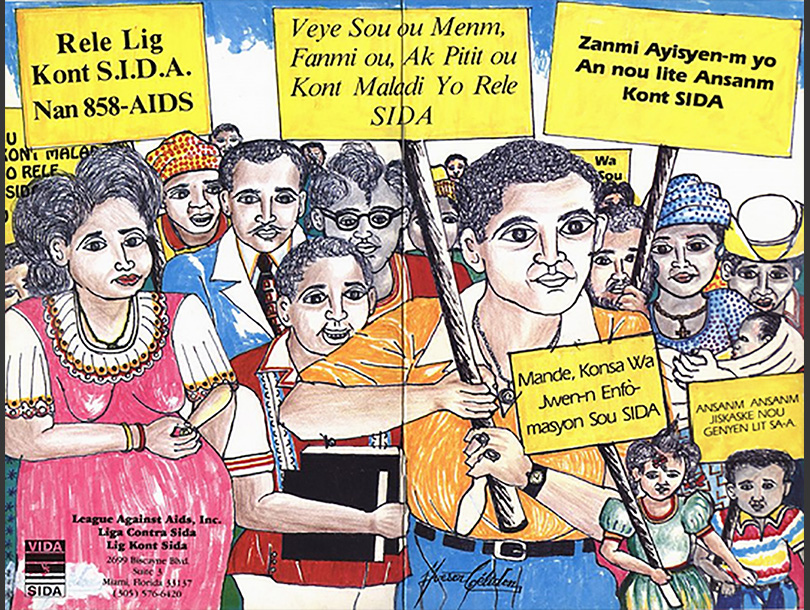

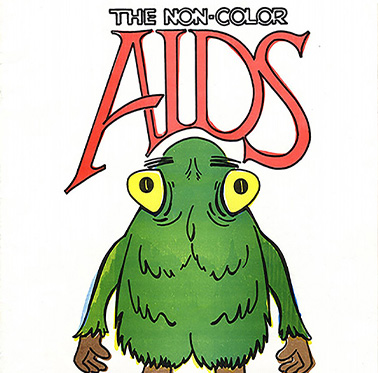

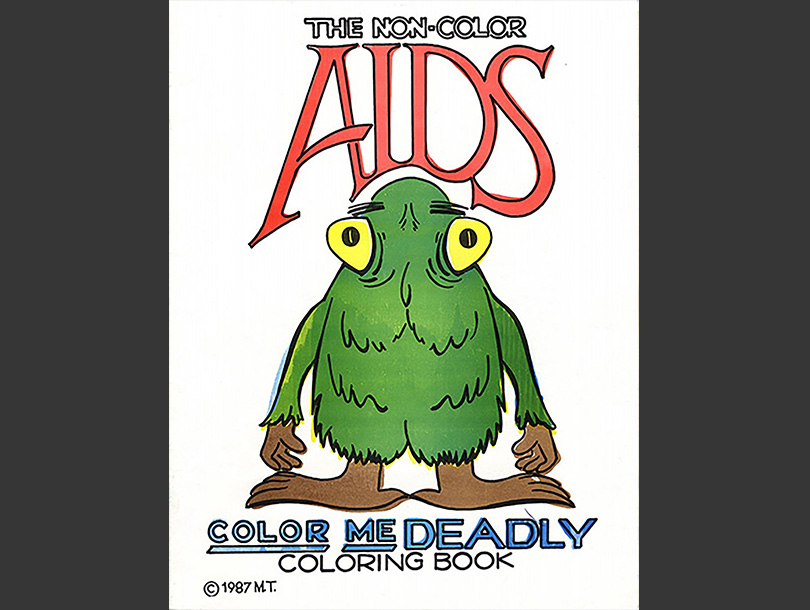

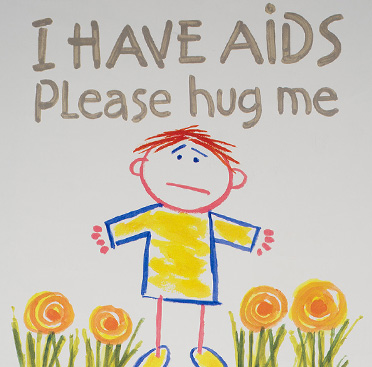

The fear of AIDS and resulting stigma for those facing the disease made getting accurate information to diverse audiences more difficult. Many people were afraid even to ask questions, lest they be marked with the societal shame then associated with AIDS. These posters and booklets, all designed for general audiences by various AIDS service organizations, reflected a variety of strategies to promote the spread of facts about the disease instead of rumors. They reminded people that everyone needed to have accurate information about AIDS and places where that information existed.

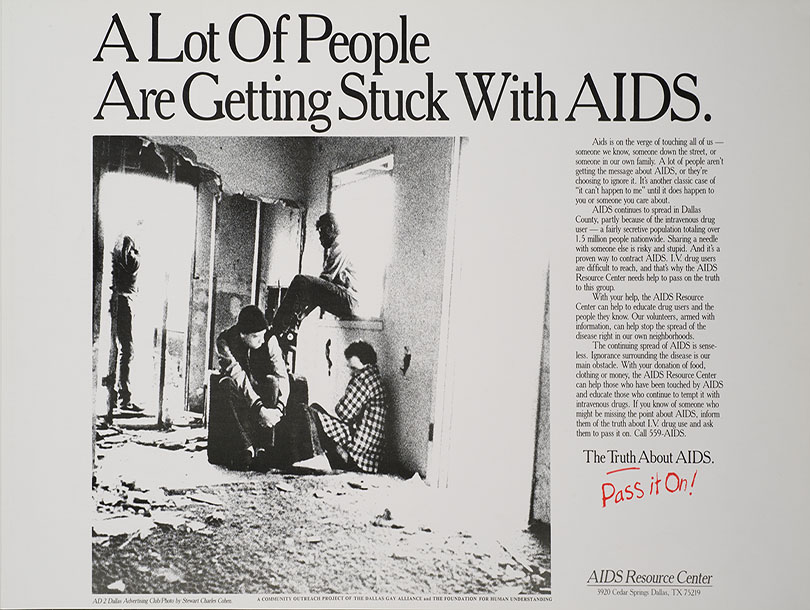

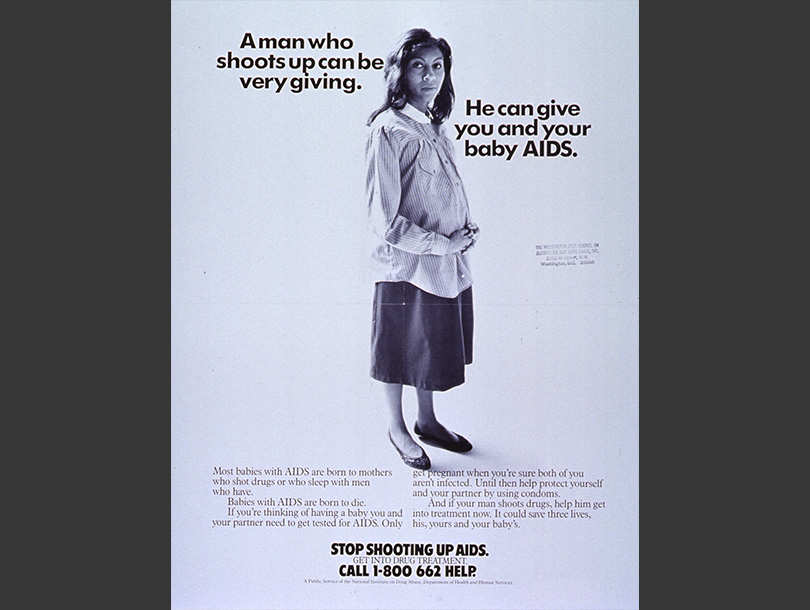

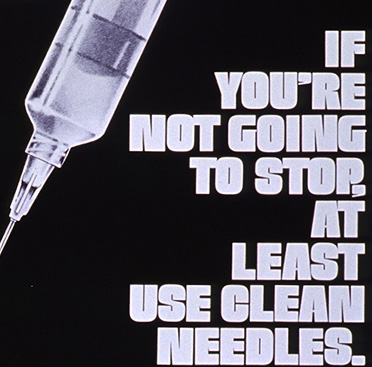

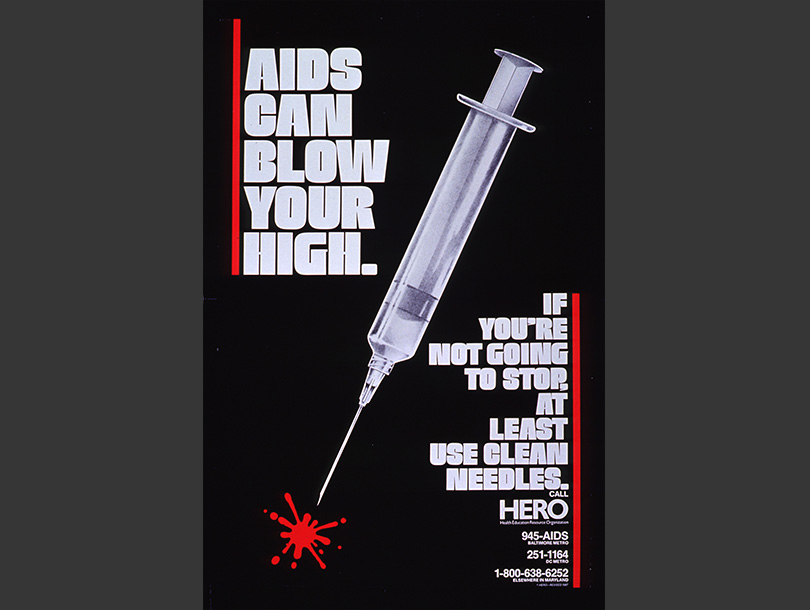

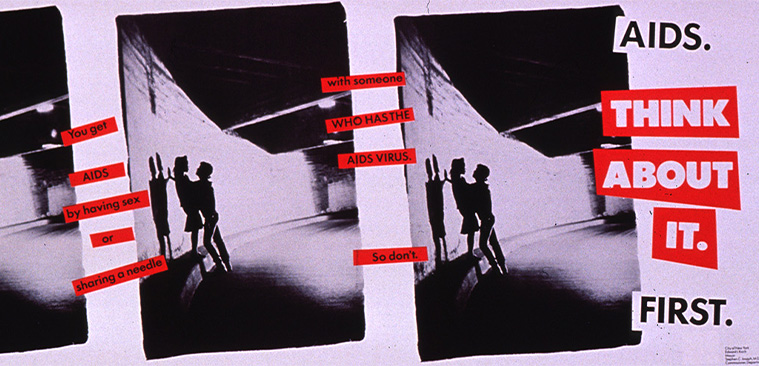

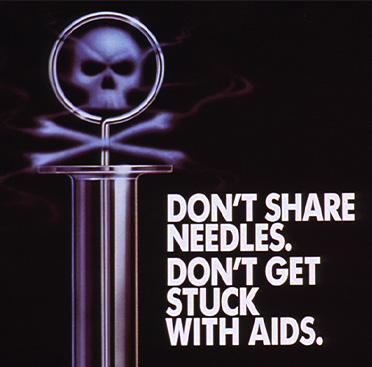

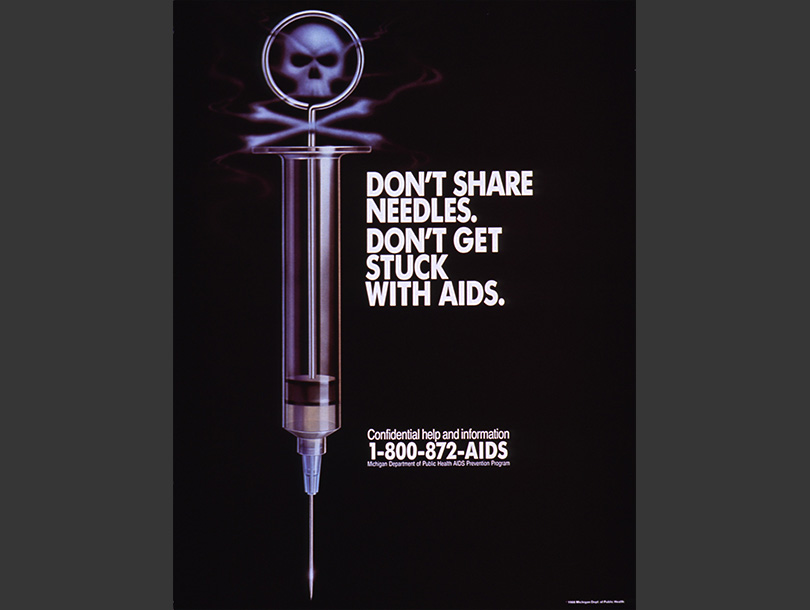

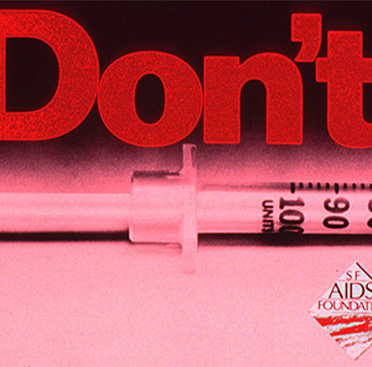

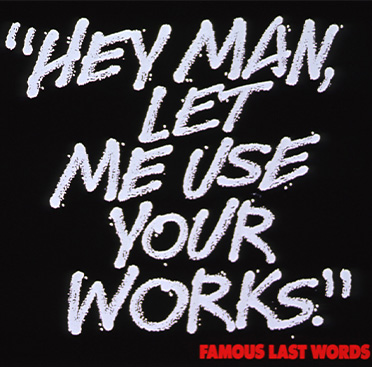

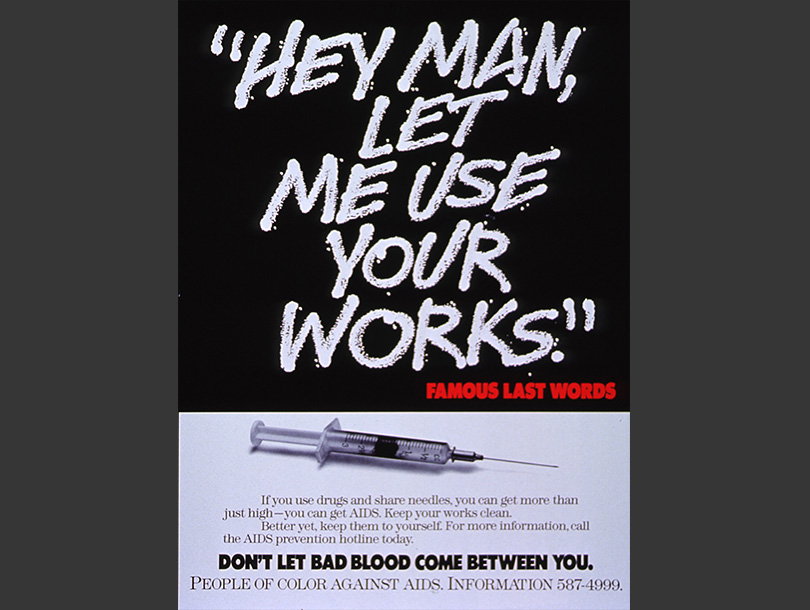

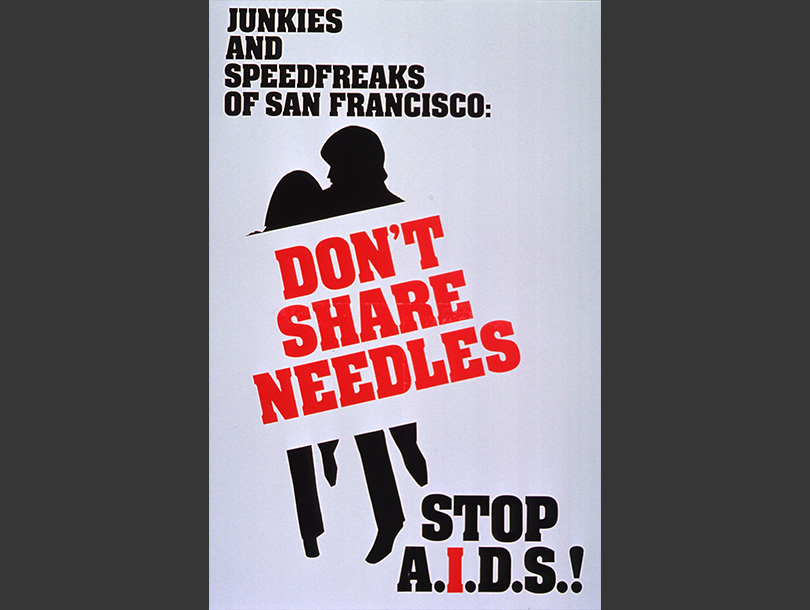

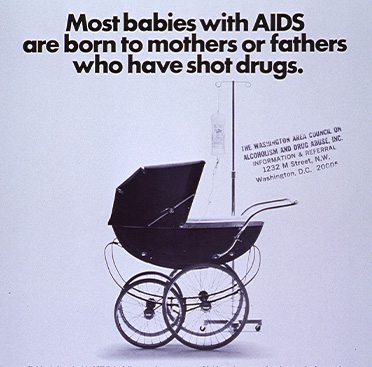

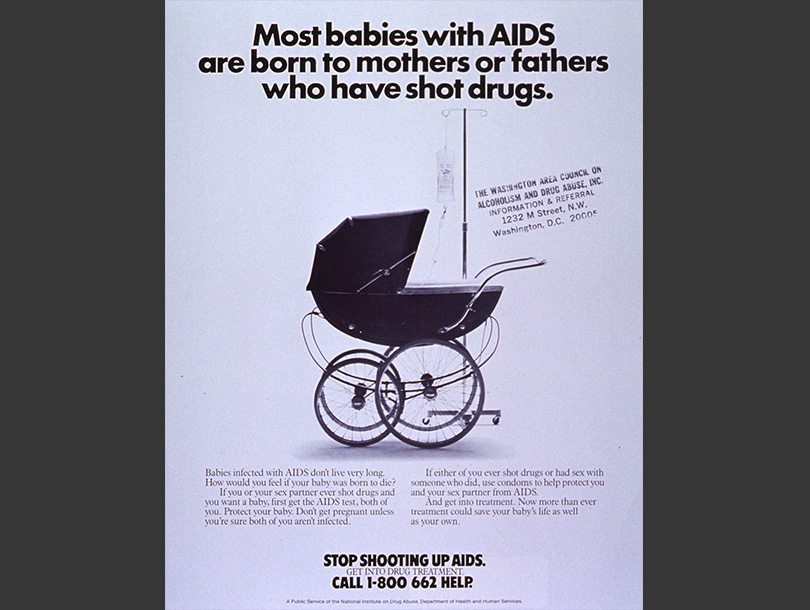

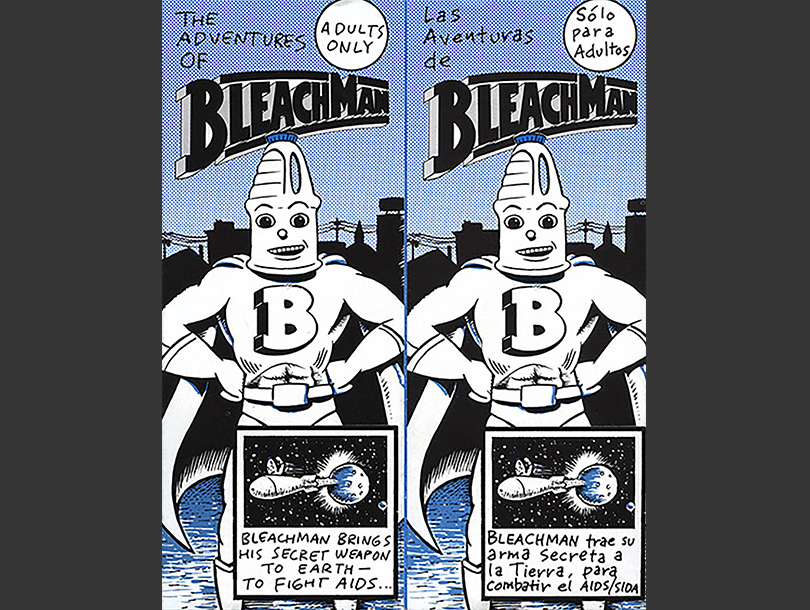

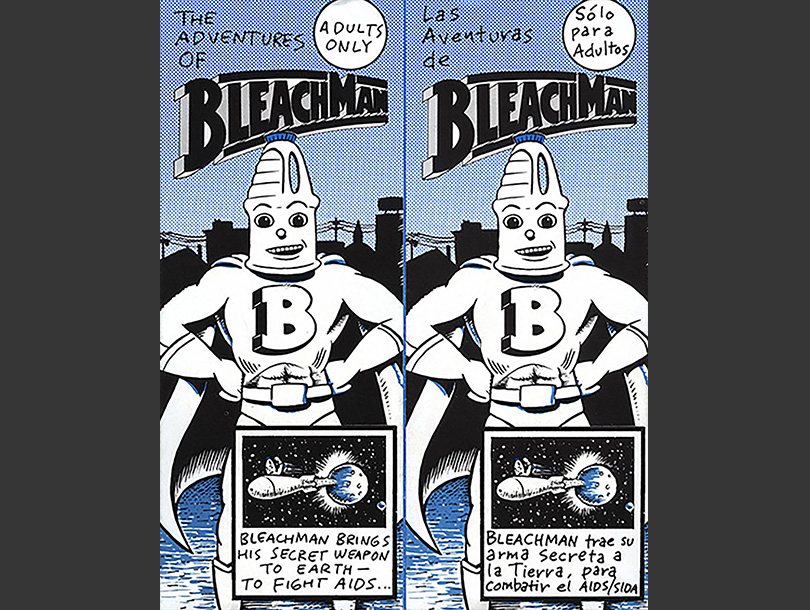

View images in this themeHarm Reduction/Clean Needles

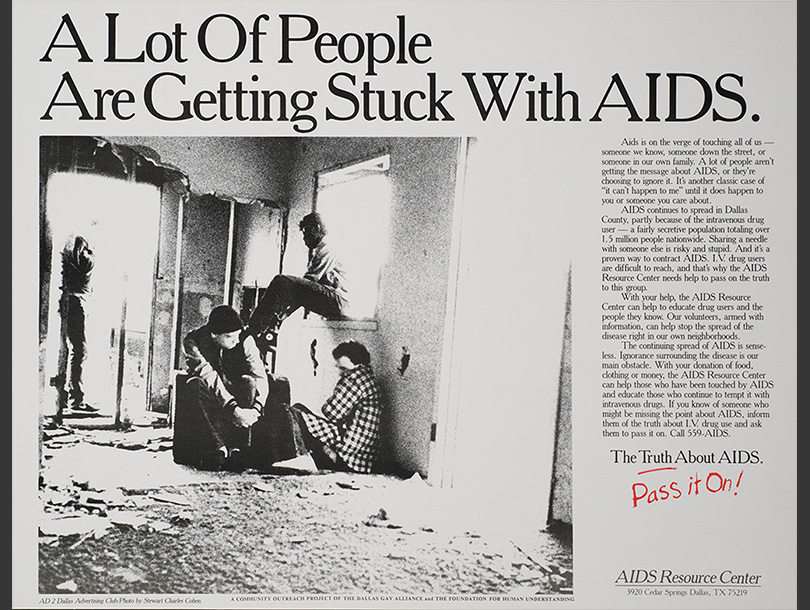

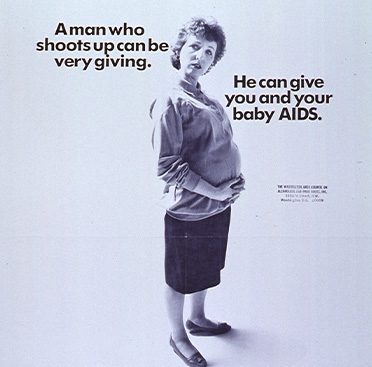

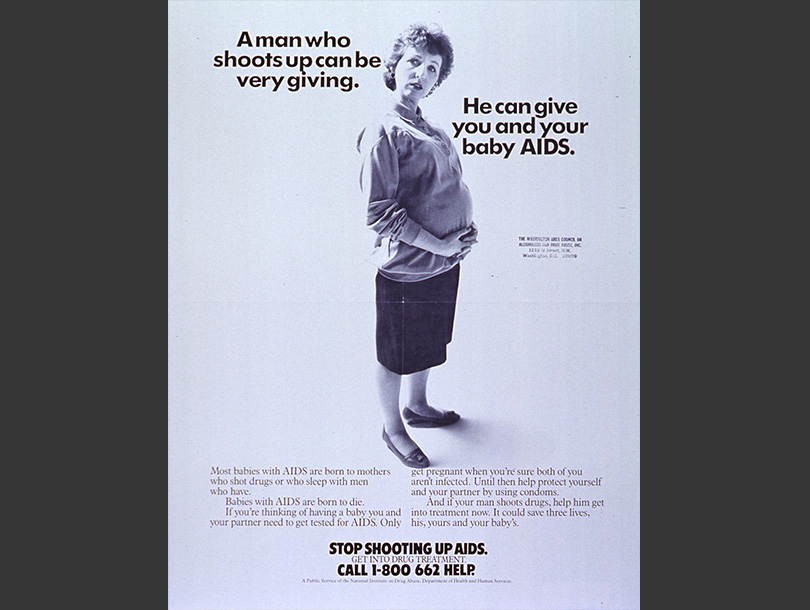

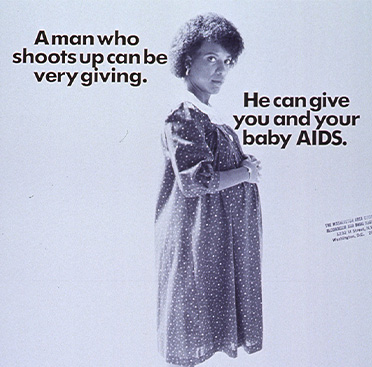

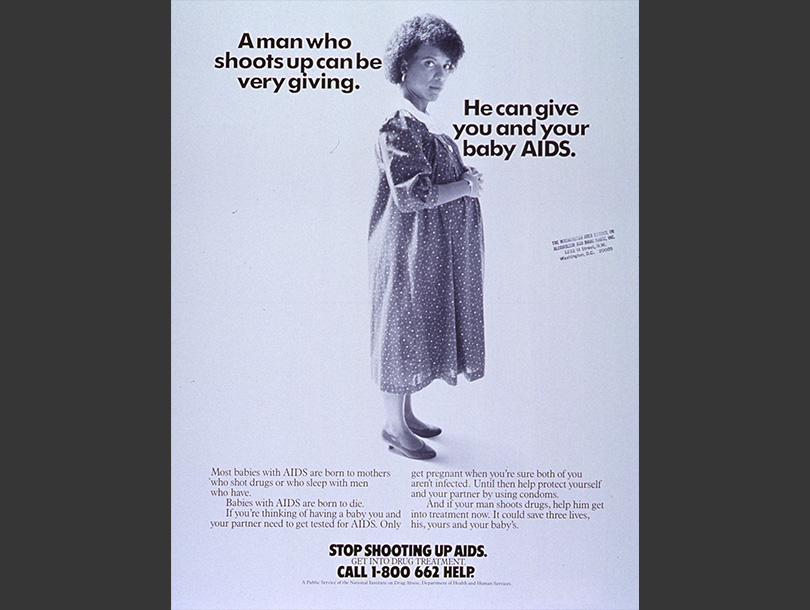

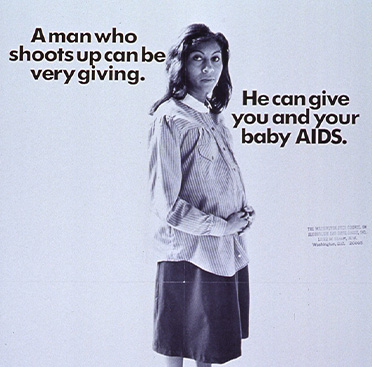

In the early 1980s, many believed that identity not behavior put people at risk for contracting AIDS. Known collectively as the 4 H’s: homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin users (representing all intravenous drug users), and Haitians, the four groups were considered vulnerable and blamed for spreading the disease. Intravenous drug users brought with them an all-too-familiar public health challenge. How do you inform, protect, and support a group that engages in behaviors deemed illegal and potentially considered wrong or sinful?

One answer, as illustrated in these public health campaigns, was harm reduction—the idea that if you could not stop people from using intravenous drugs, you could, at least, get them information about how to protect themselves while doing so. Using blunt, straightforward language, these campaigns spoke to needle users and the people who had sex with them. For general audiences, those who might see the materials in passing, harm-reduction campaigns underscored the idea that disliking or disapproving of a risky behavior was inconsequential: value judgments did nothing to prevent the spread of AIDS.

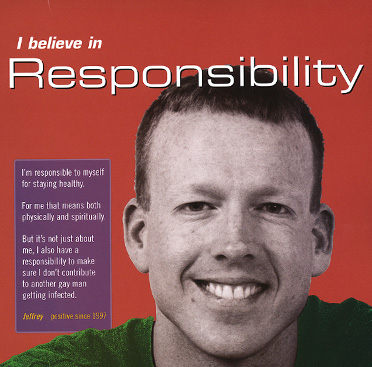

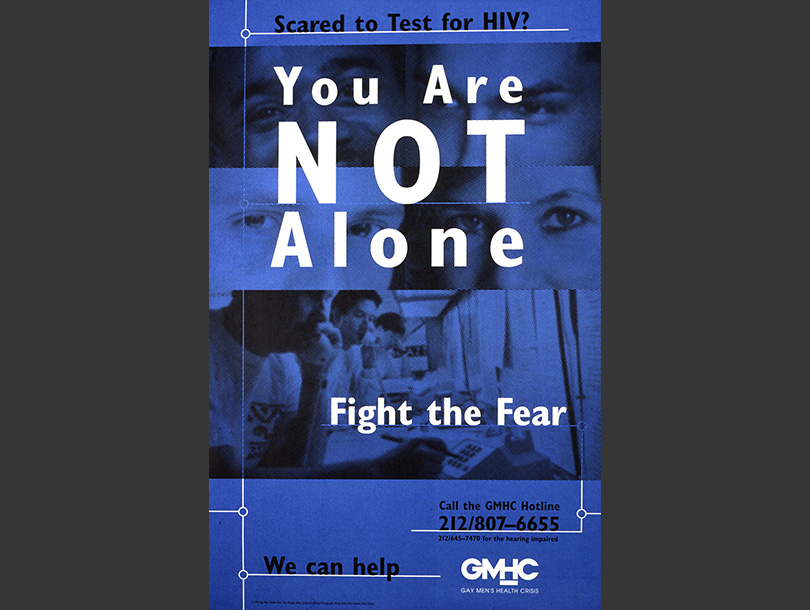

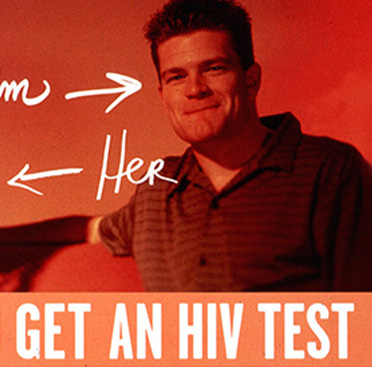

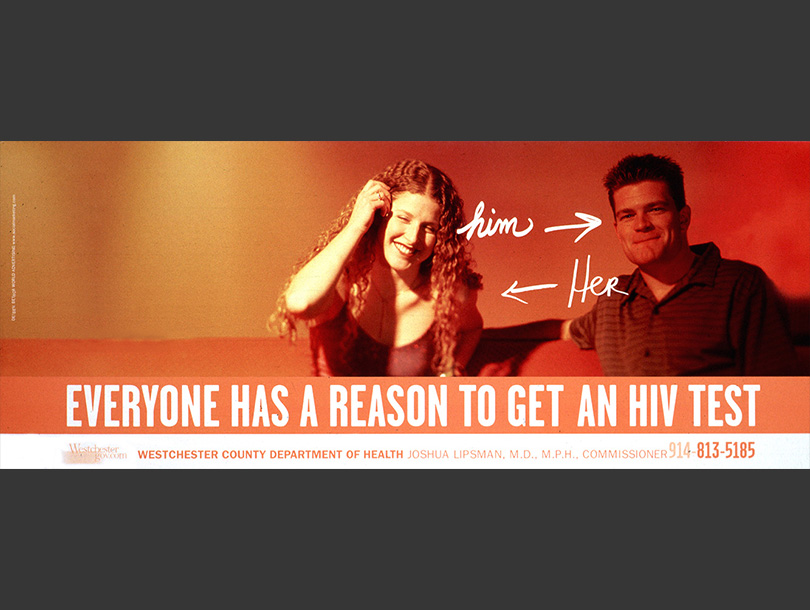

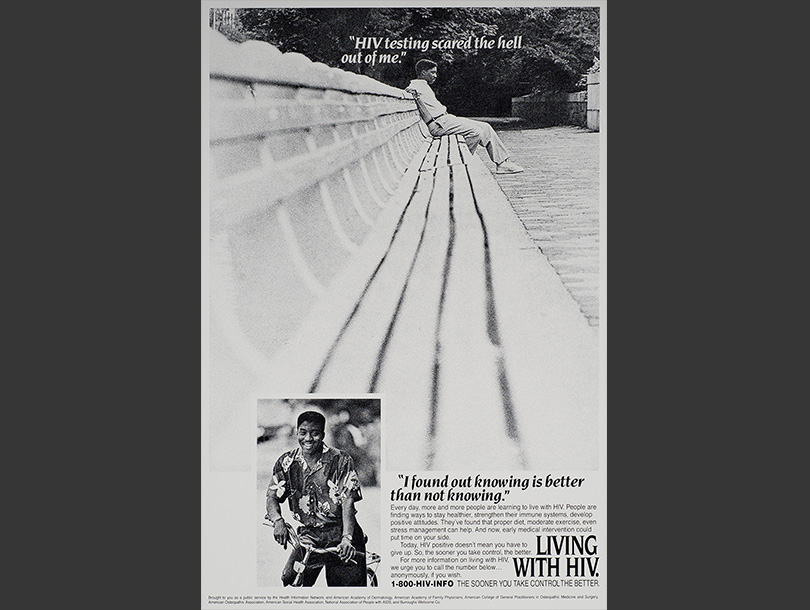

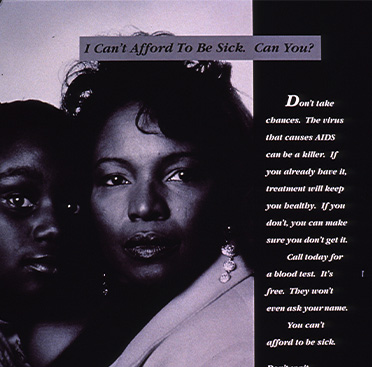

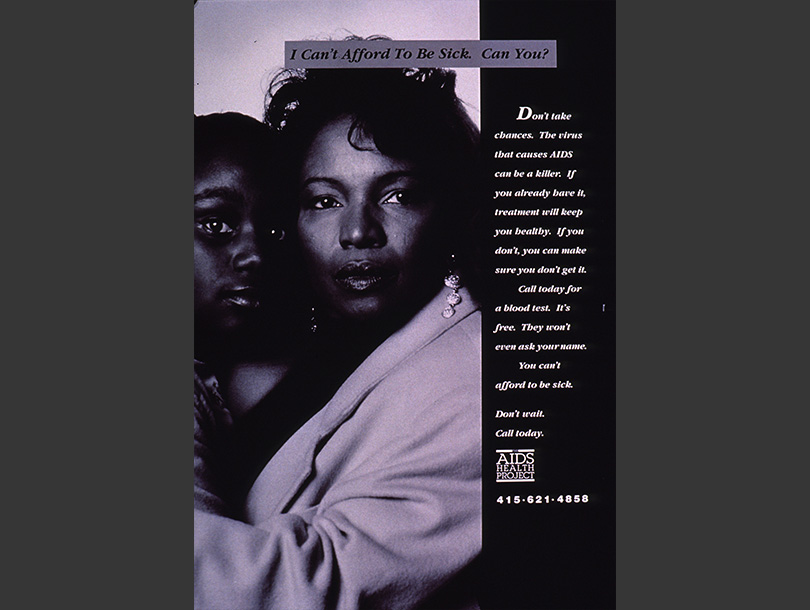

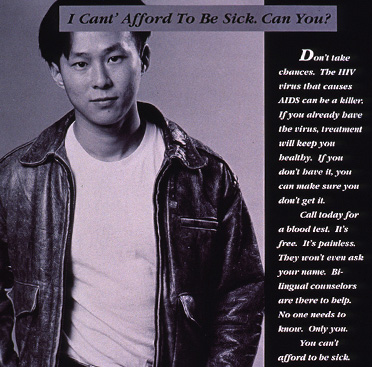

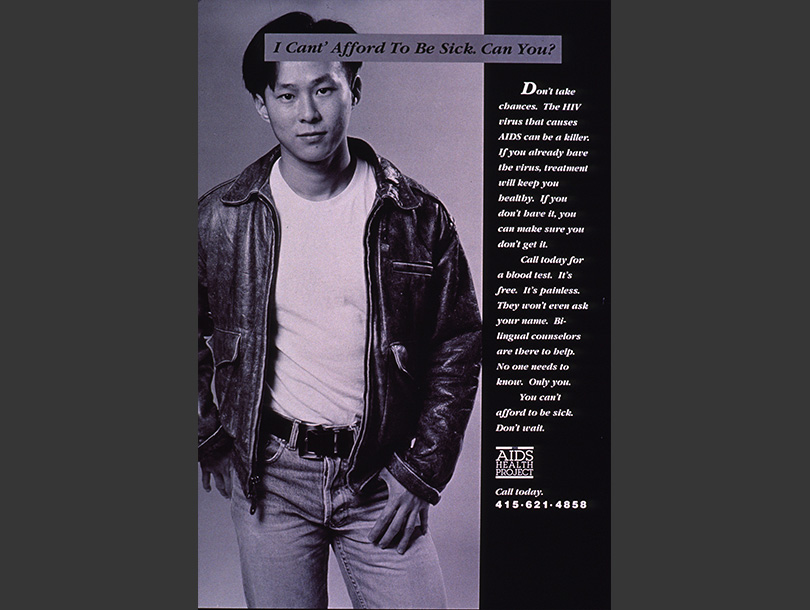

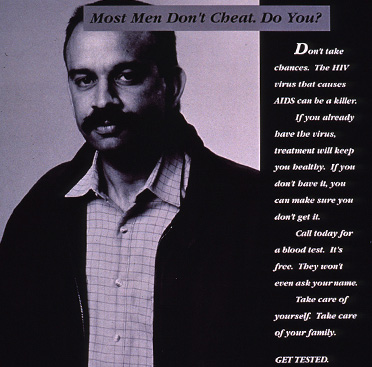

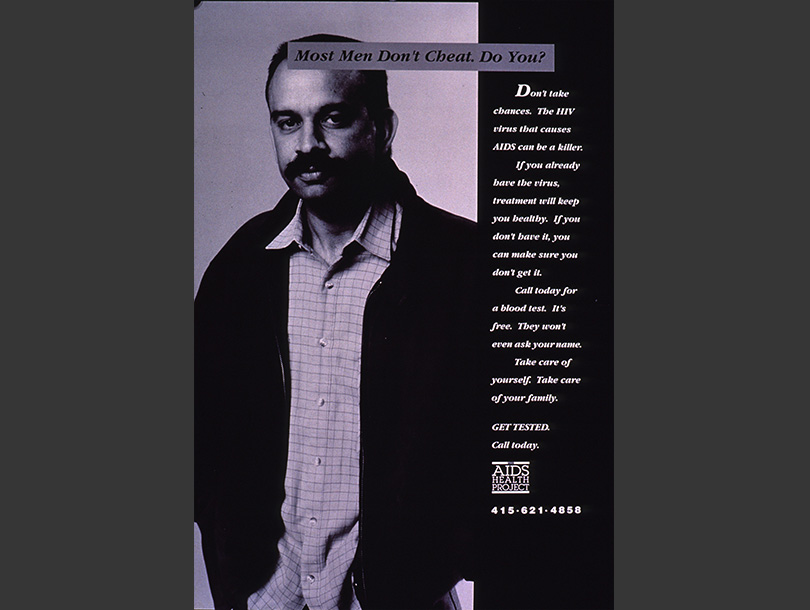

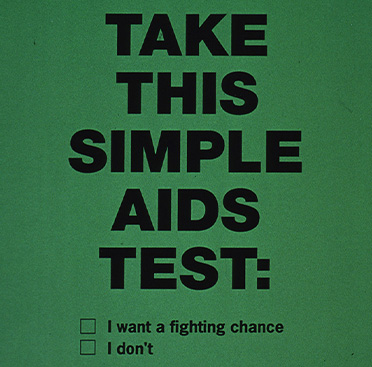

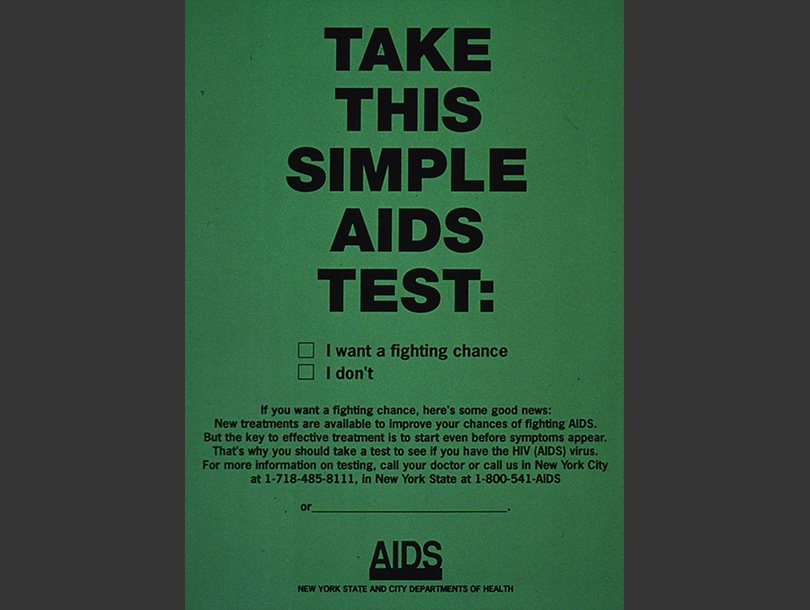

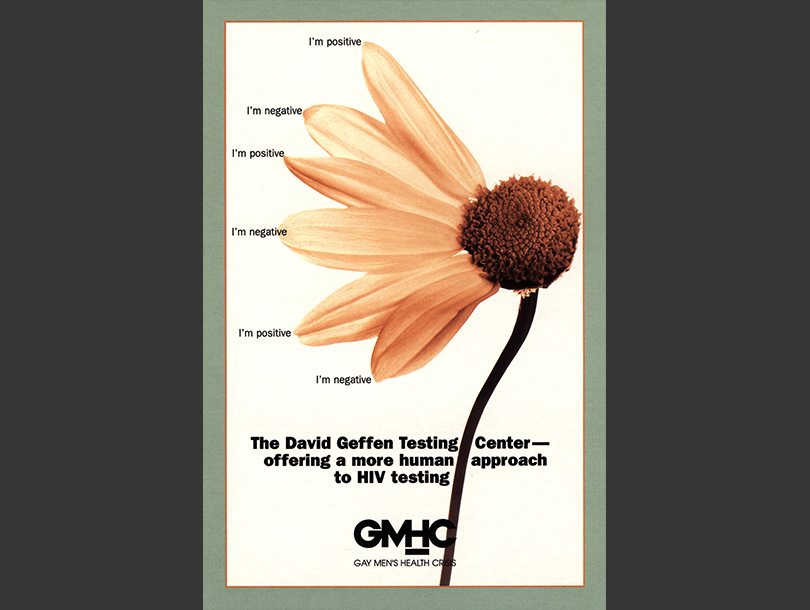

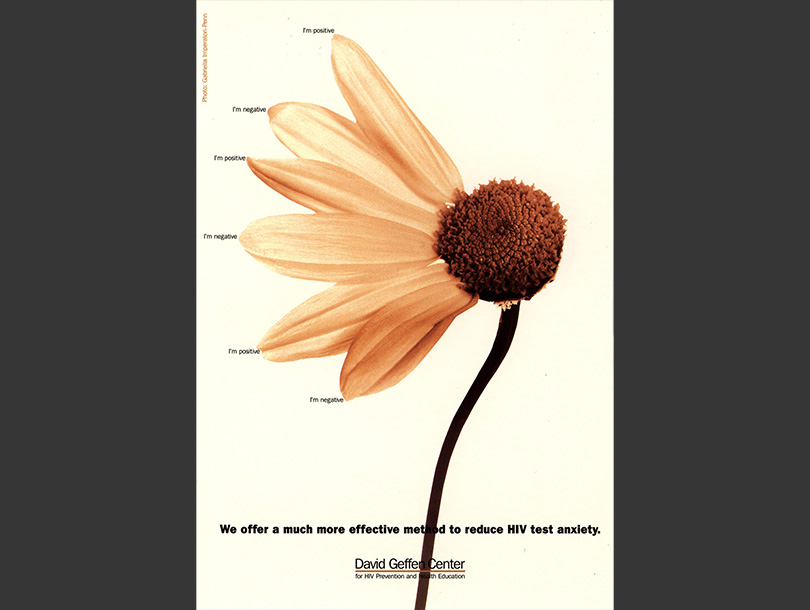

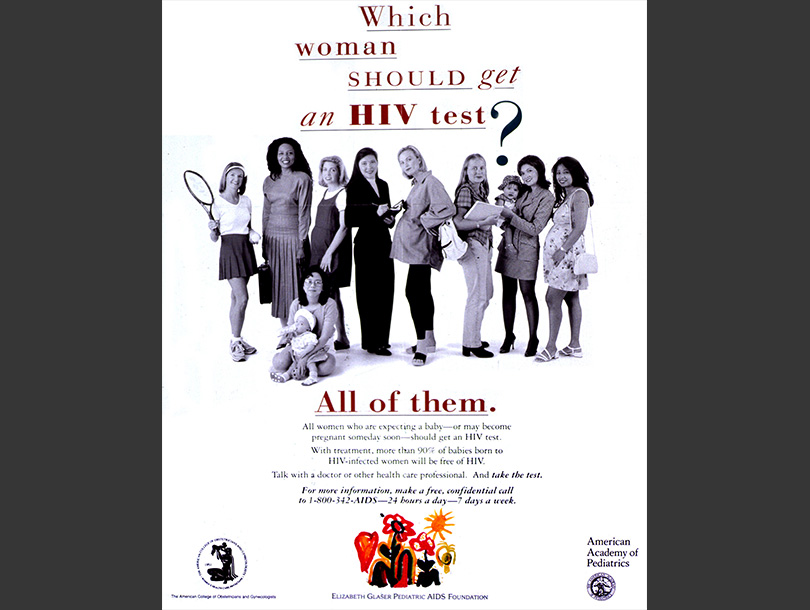

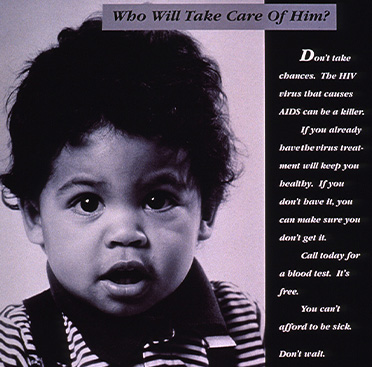

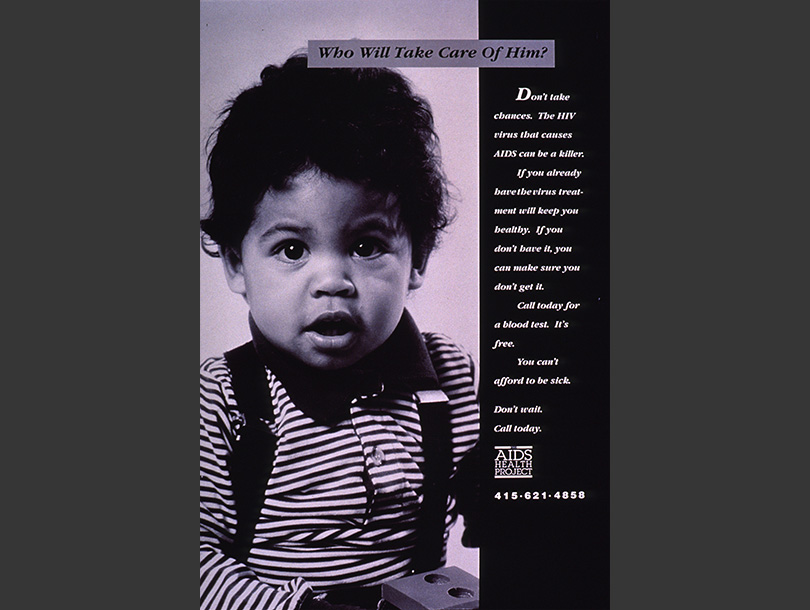

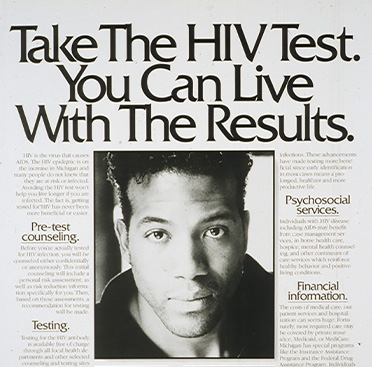

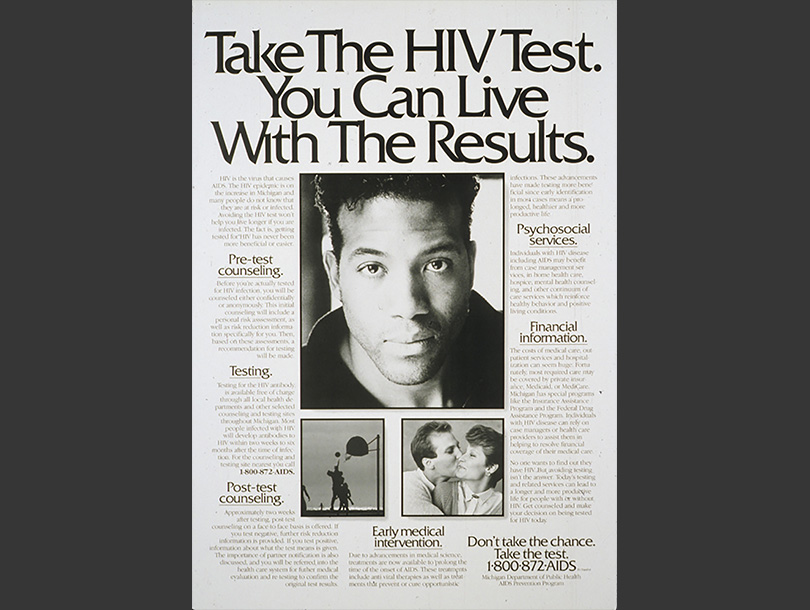

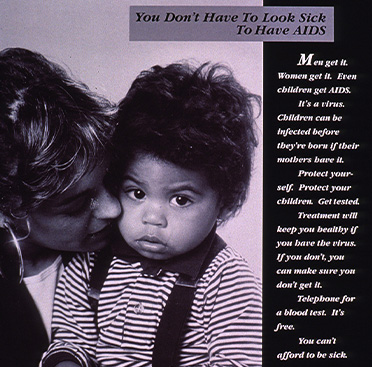

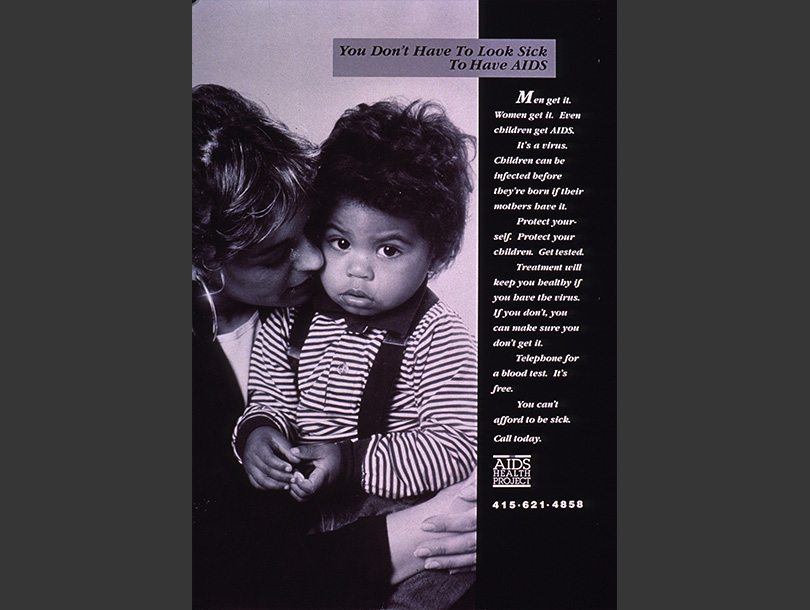

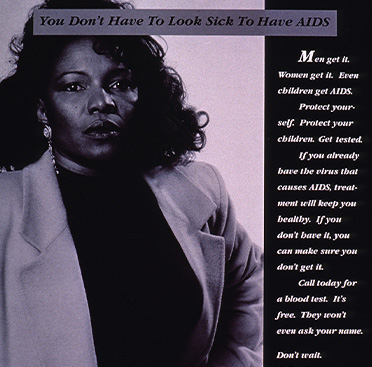

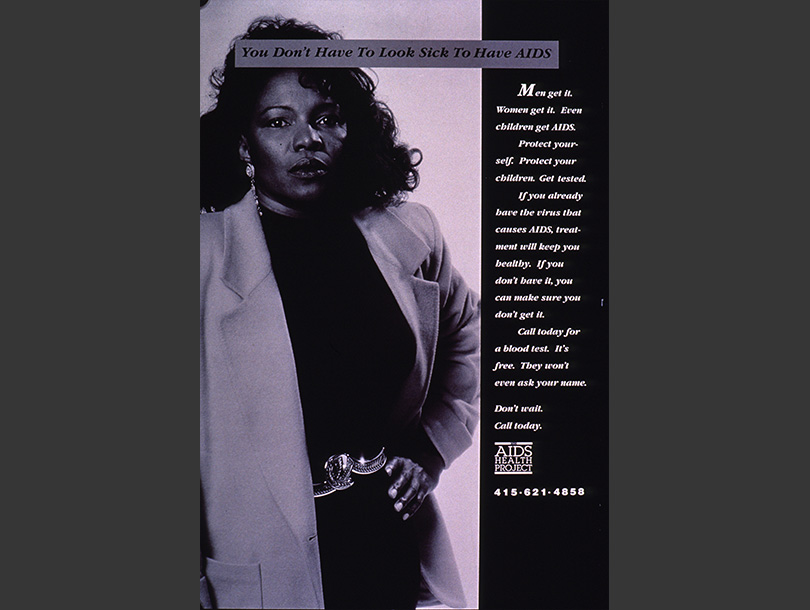

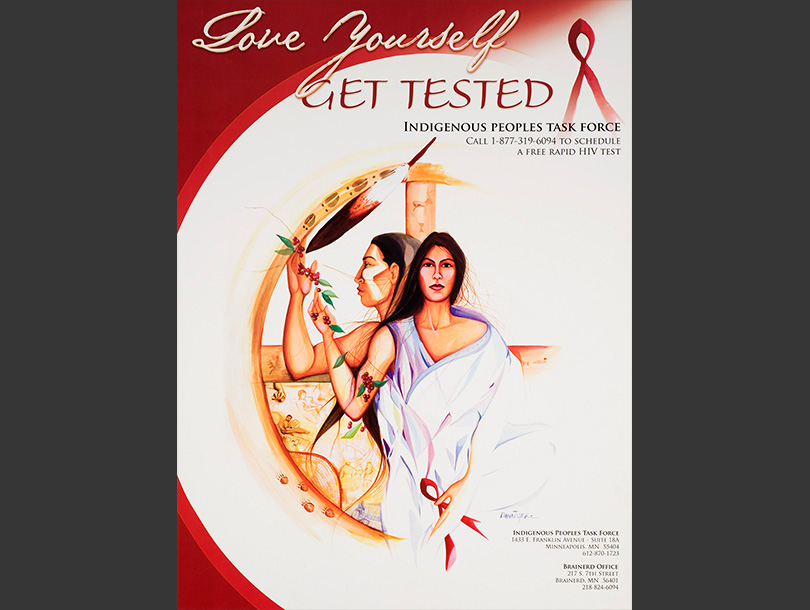

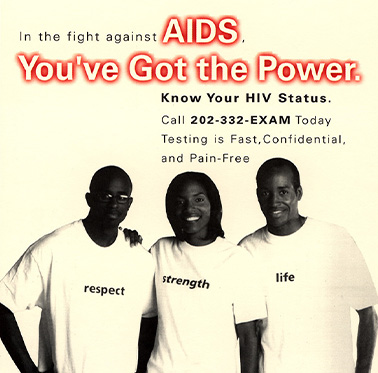

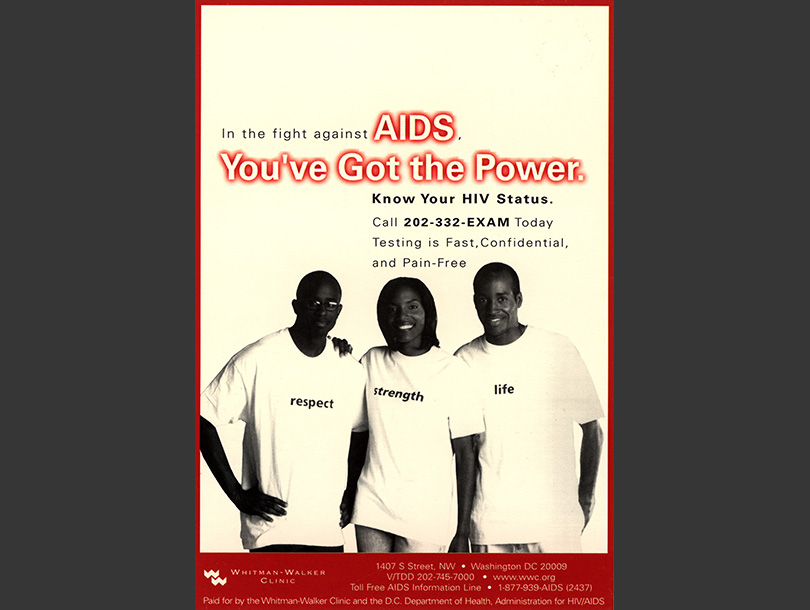

View images in this themeHIV Testing

Blood tests to detect the presence of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) first became available in 1985, after scientists and public health officials confirmed that the virus caused AIDS. Testing made it possible to diagnose HIV before symptoms surfaced and quickly became one of the most widely practiced responses to AIDS. While many public health officials and citizens considered testing a way to take control of one’s own health, this sentiment was not always widely held.

Until 1987, when the medical establishment introduced AZT (azidothymidine), the first widely available, yet exorbitantly expensive, drug to slow HIV infection, many service providers, particularly ones who worked with communities of gay men, argued against testing. They feared that violations of privacy would outpace positive support and treatment options for people who tested positive. With testing, the prospect of a sudden, painful, seemingly random AIDS-related death was replaced with a similarly terrible future of stigma, isolation, and misdirected hatred resulting from a positive HIV test.

These campaigns encouraged people to overcome their fear of the disease and the stigma it produced by stressing personal and social responsibility as well as the availability of information, support, and, later, treatment if infected with HIV.

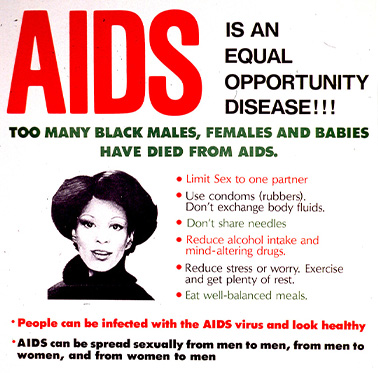

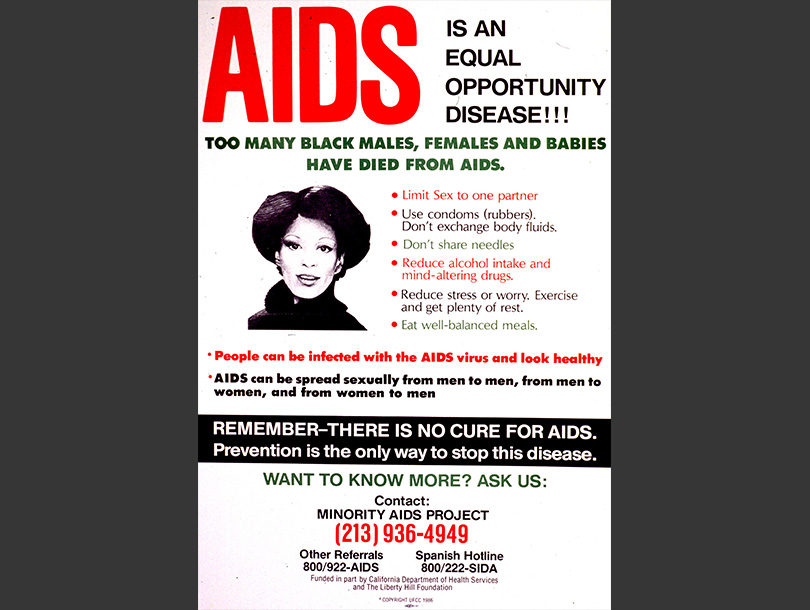

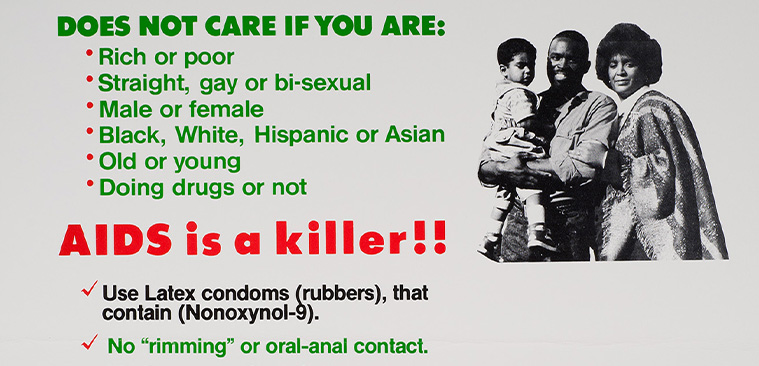

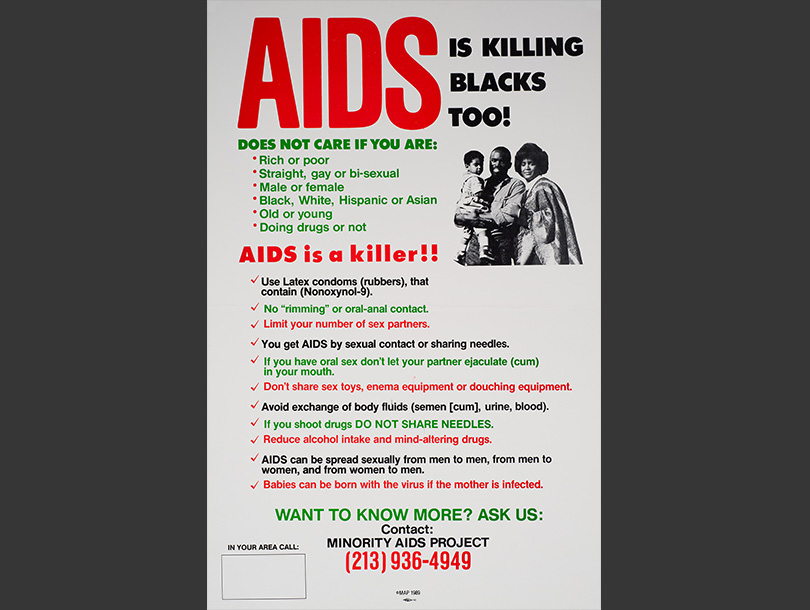

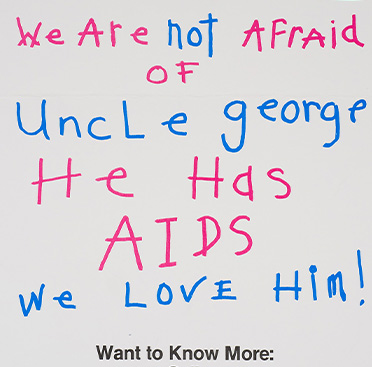

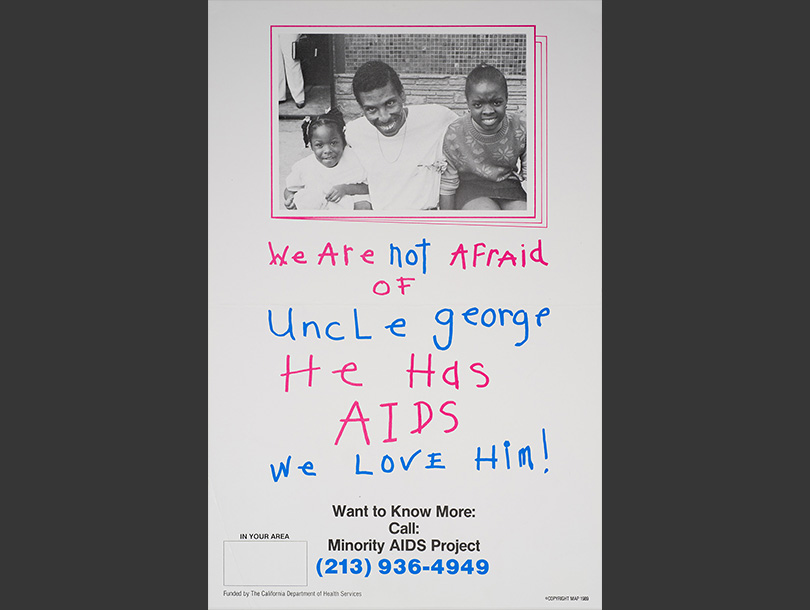

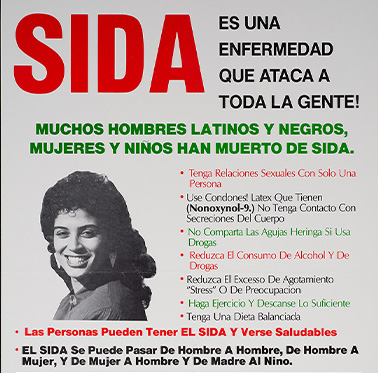

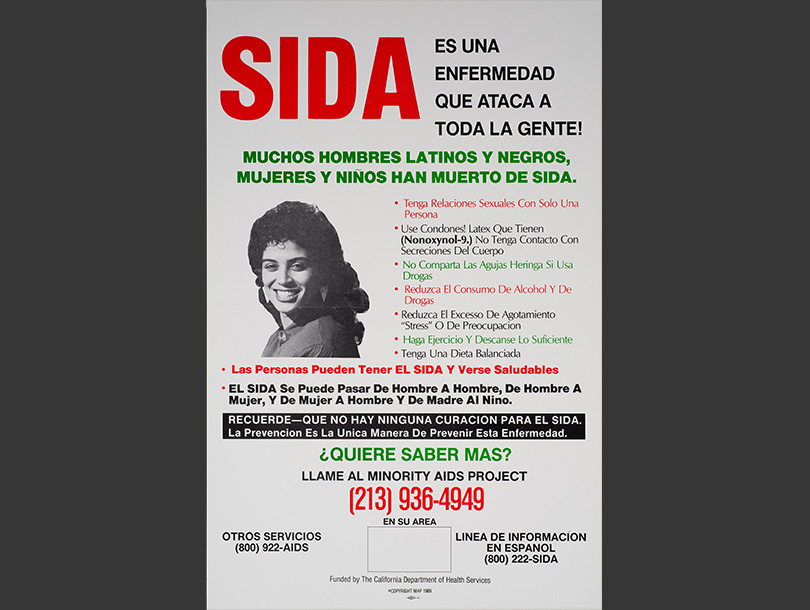

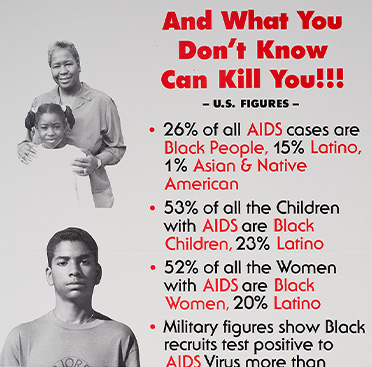

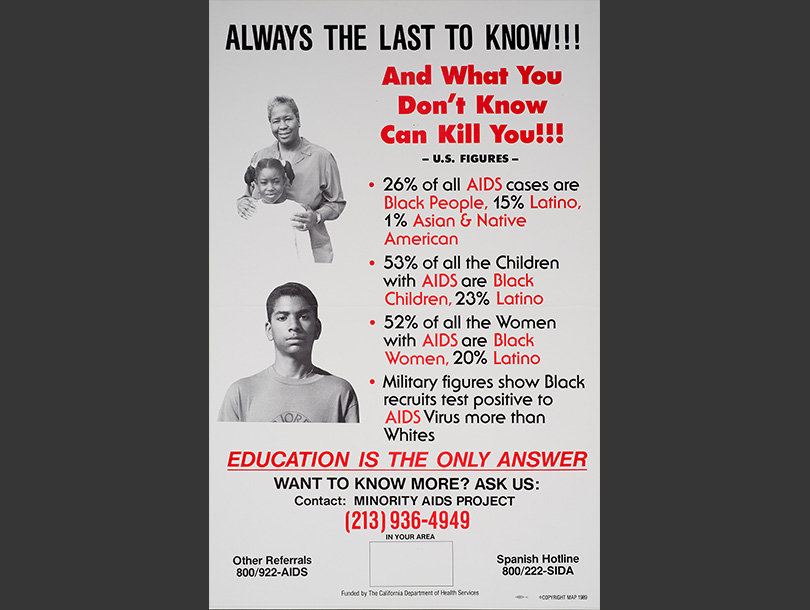

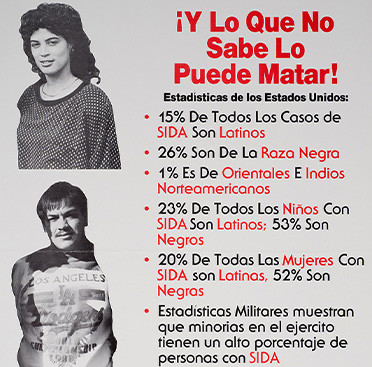

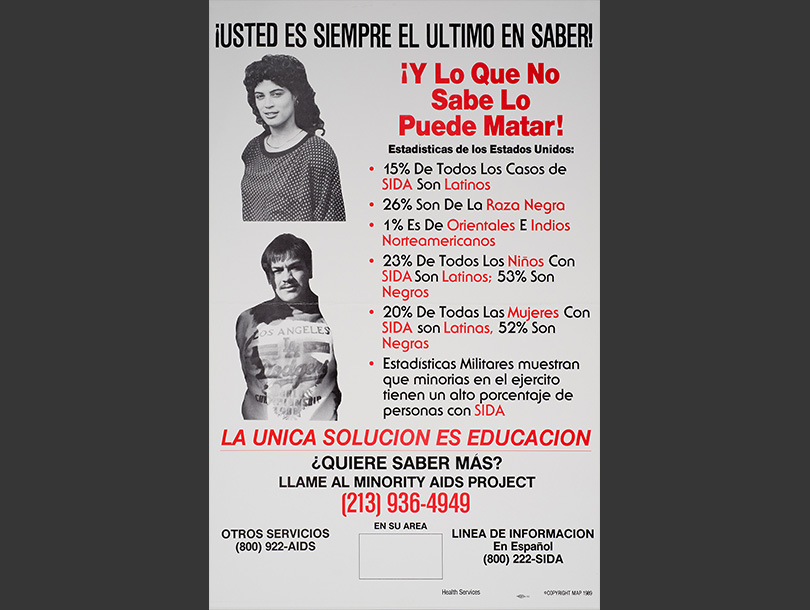

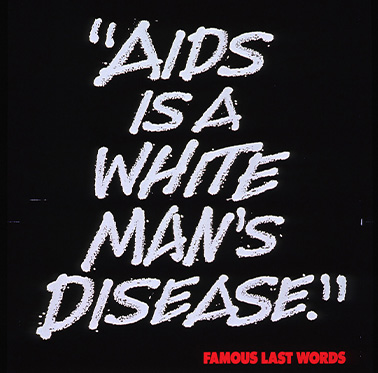

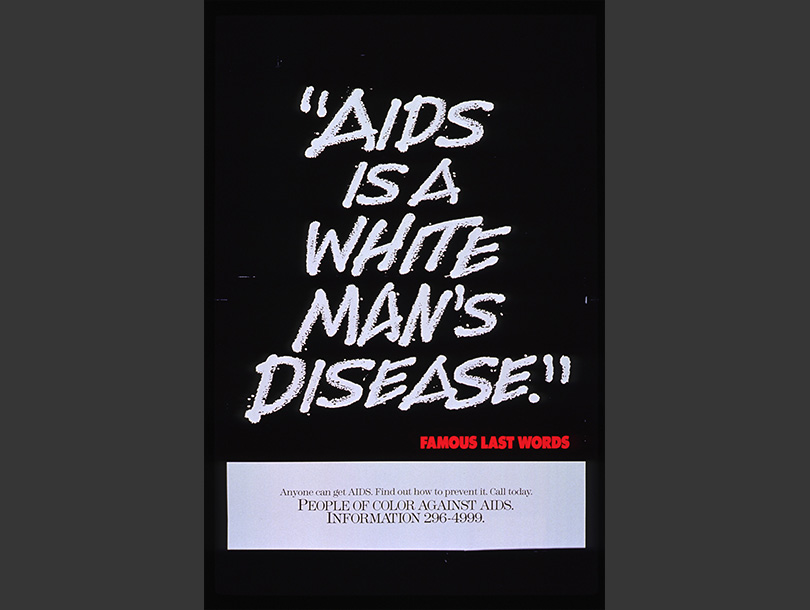

View images in this themeThe Minority AIDS Project

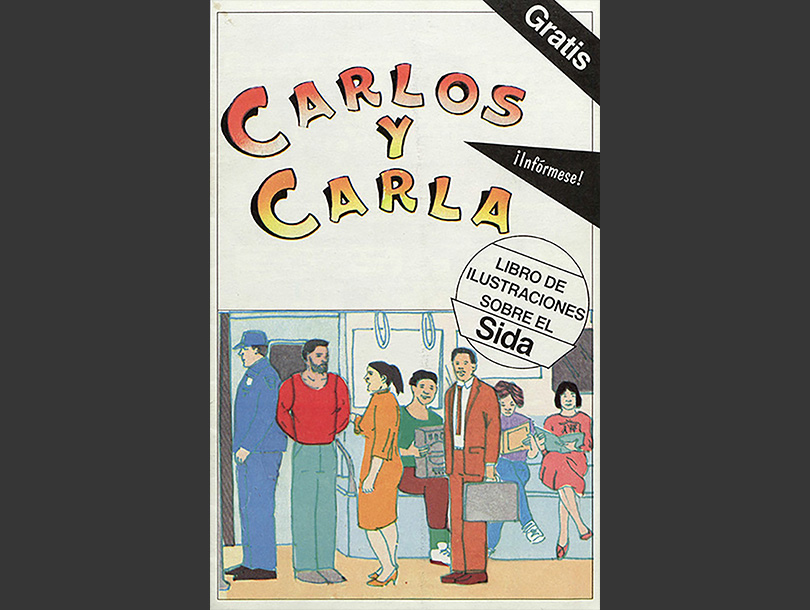

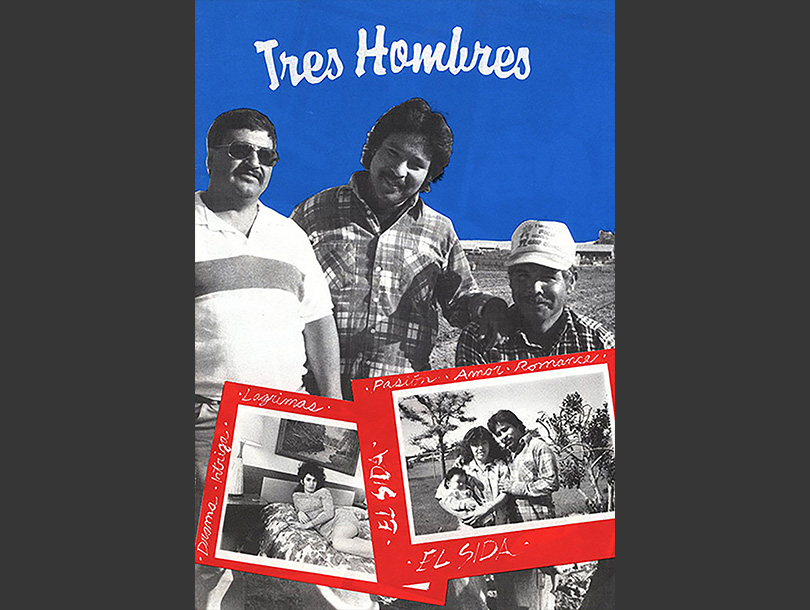

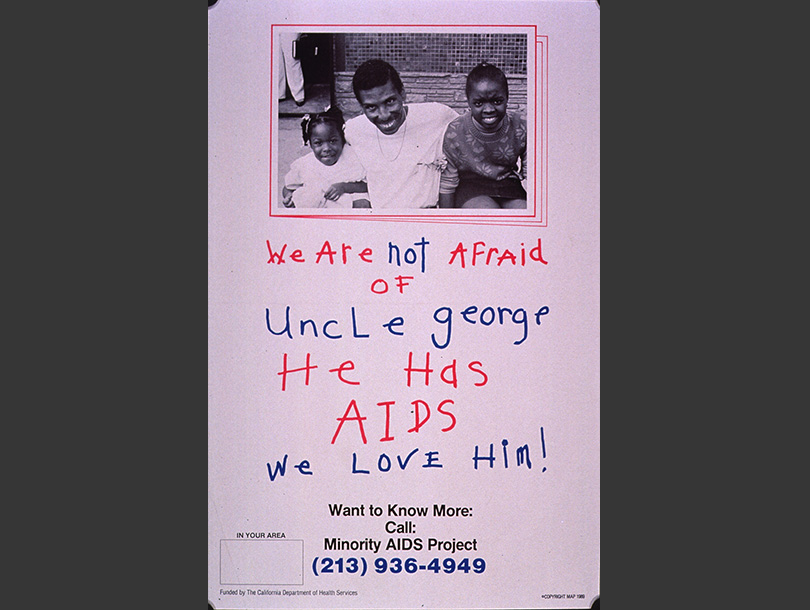

In 1985, four years into the national health crisis, African Americans and Latinos accounted for three times as many cases of AIDS as whites. To address the growing disparate epidemic and counter the myth that AIDS was a “gay white disease,” Archbishop Carl Bean and members of the Unity Fellowship Church founded the Minority AIDS Project (MAP) to support communities in southern Los Angeles. Their bold, bilingual campaigns stressed AIDS as a very serious, rapidly growing problem in communities of color and provided information on prevention and care for those with AIDS. MAP, working along side two other community-based organizations—Blacks Educating Blacks About Sexual Health Issues (BEBASHI) and Black and White Men Together—became examples for future organizations focused on assisting African Americans and Latinos affected by HIV/AIDS.

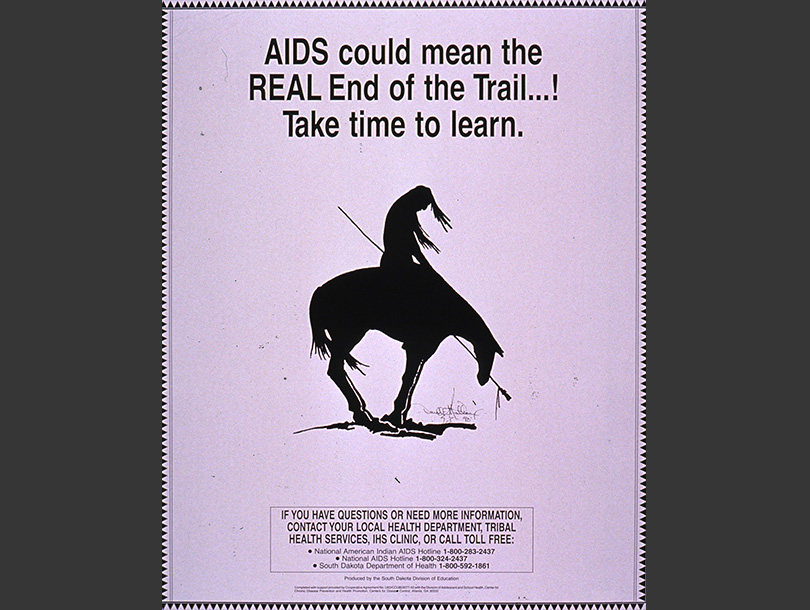

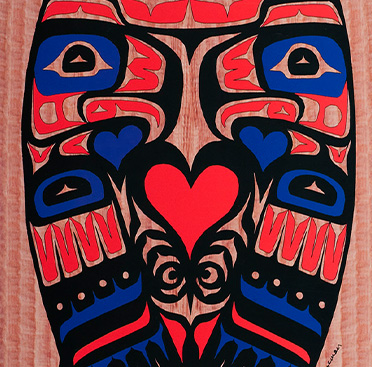

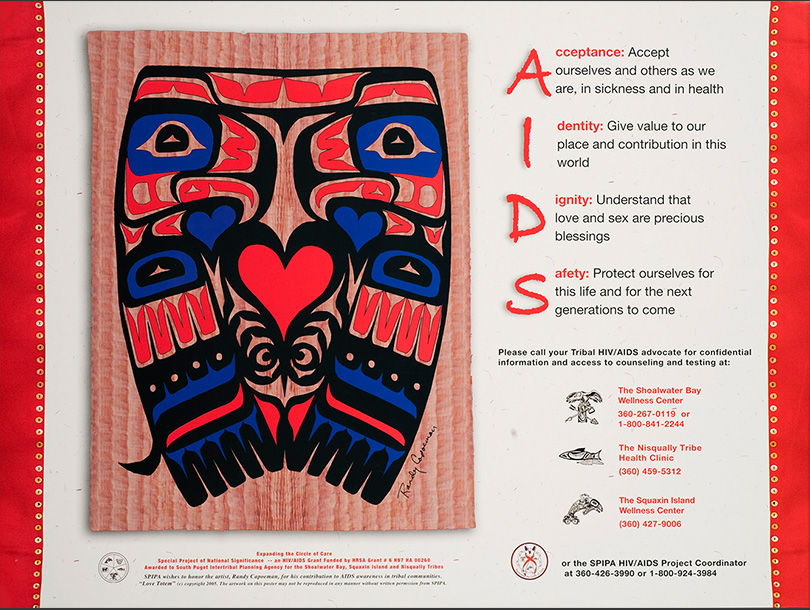

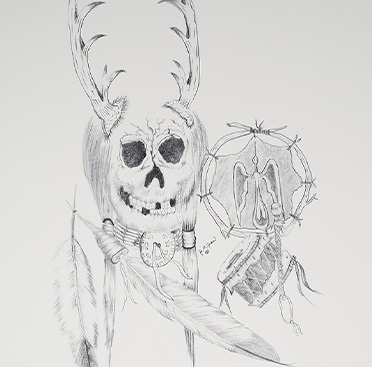

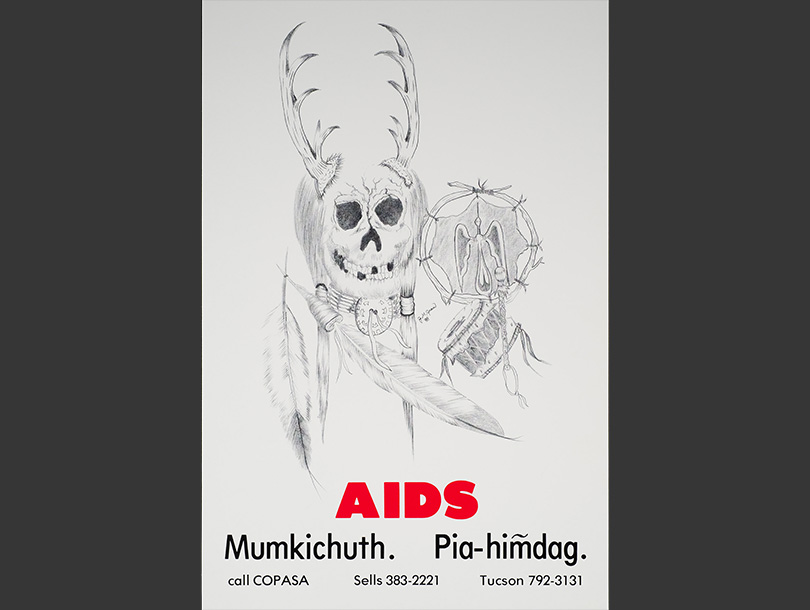

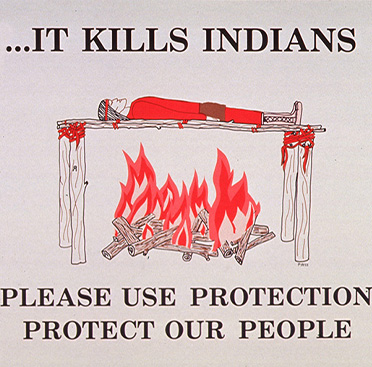

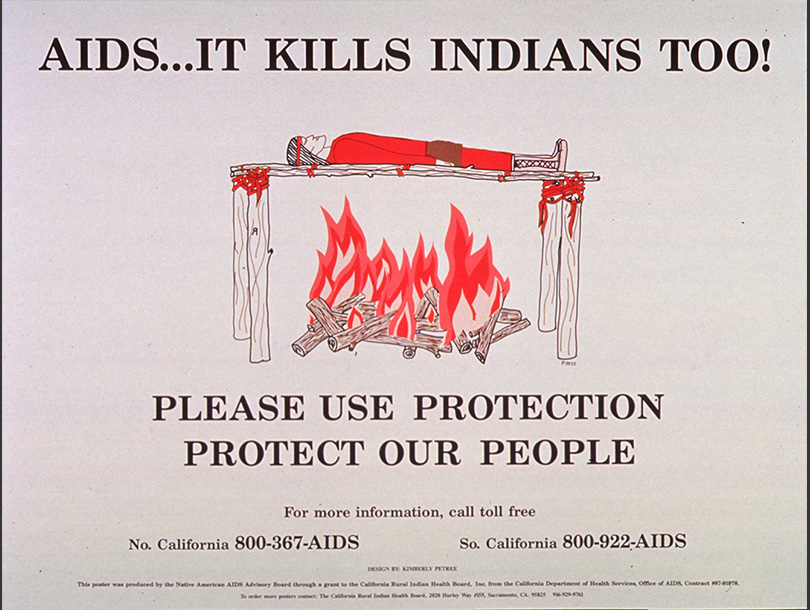

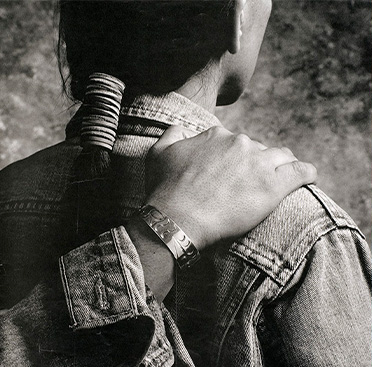

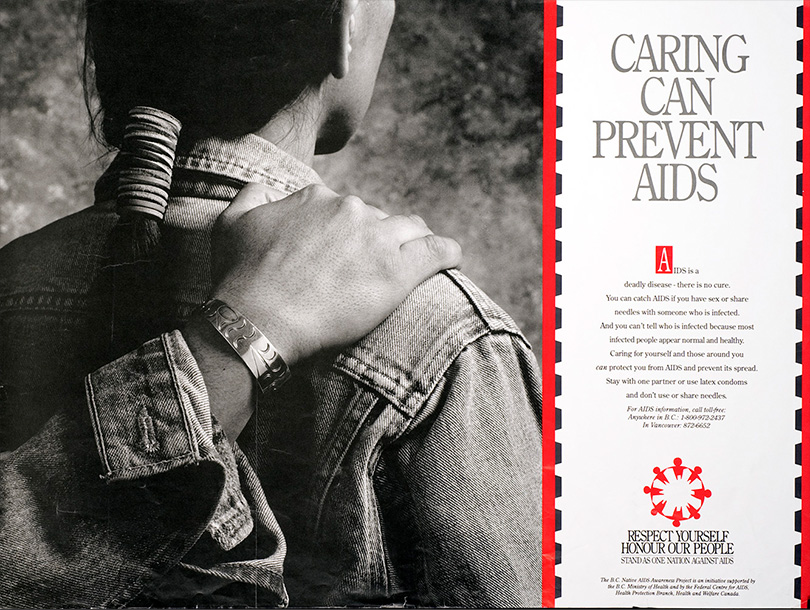

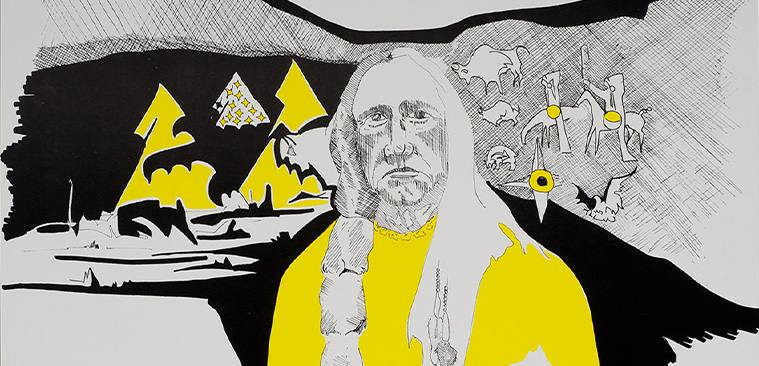

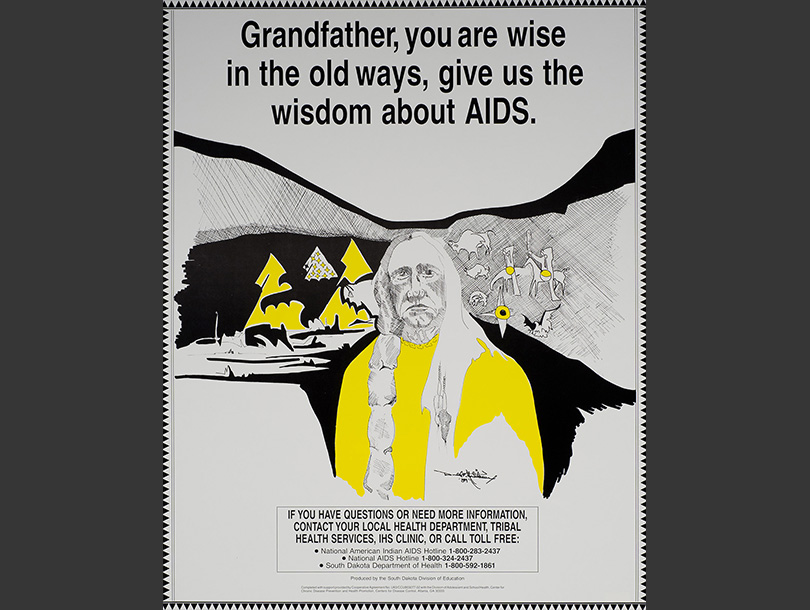

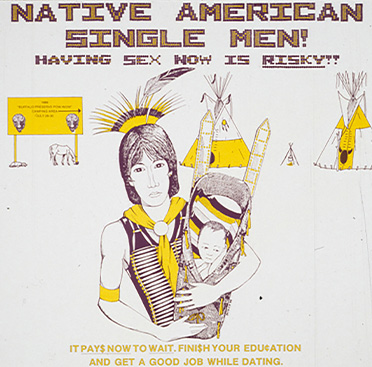

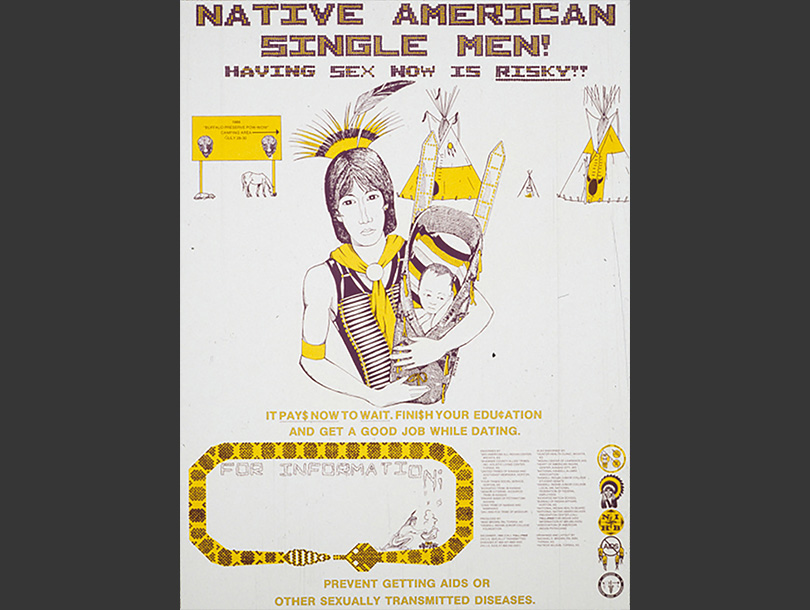

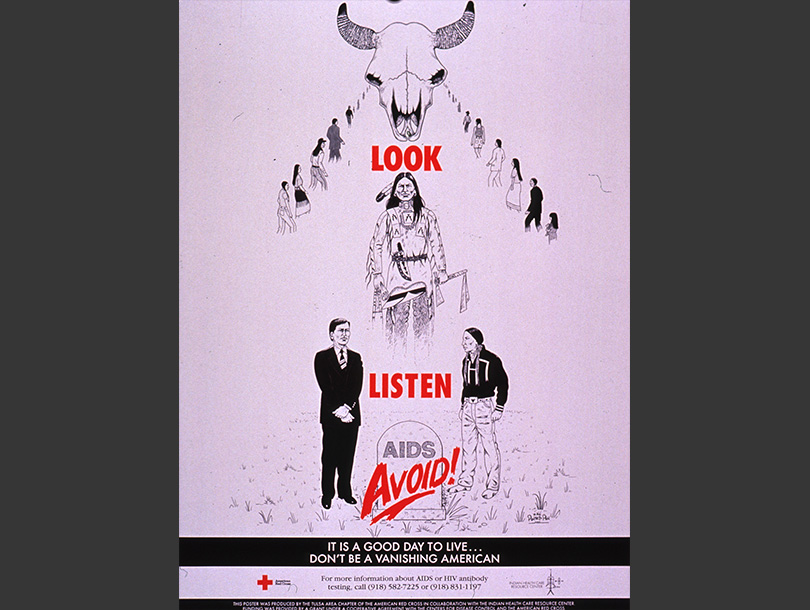

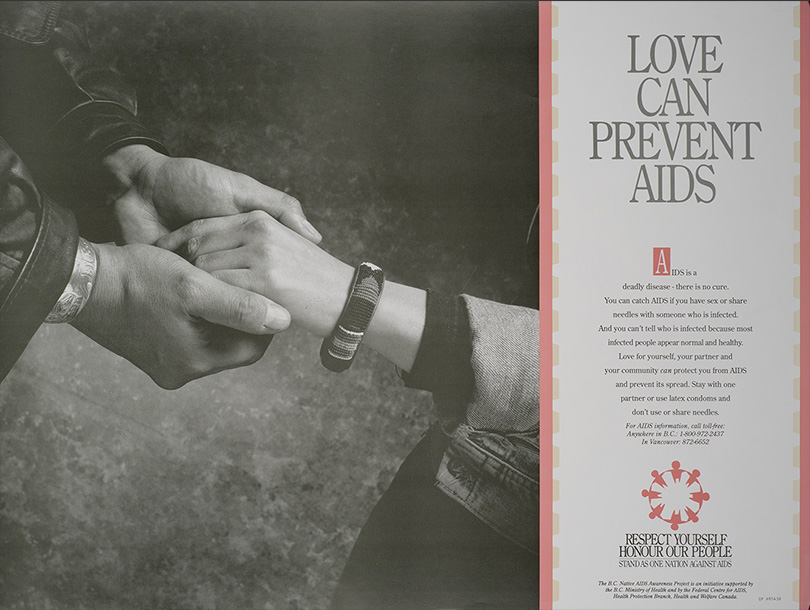

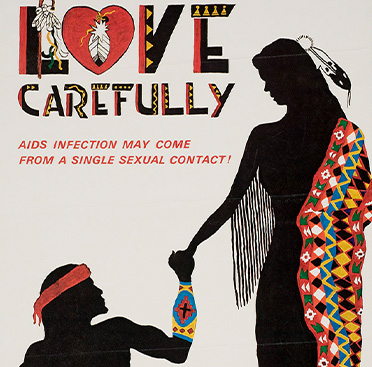

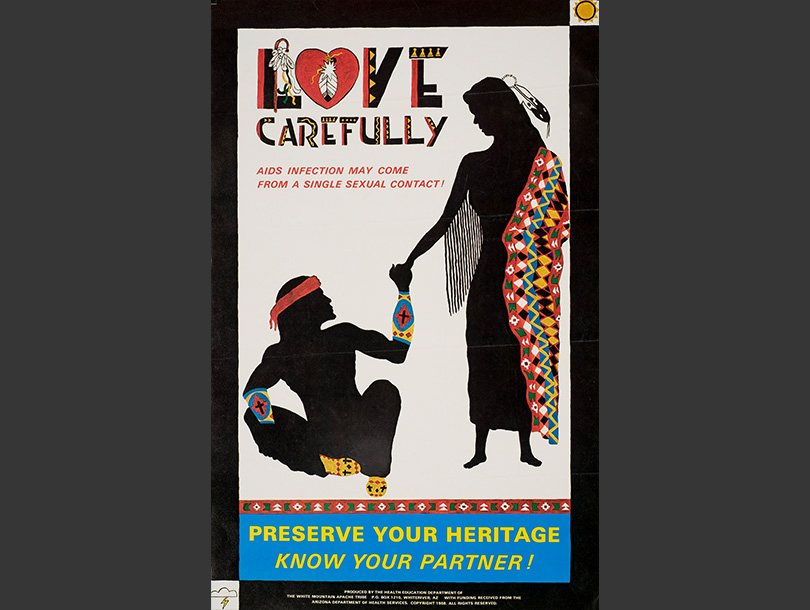

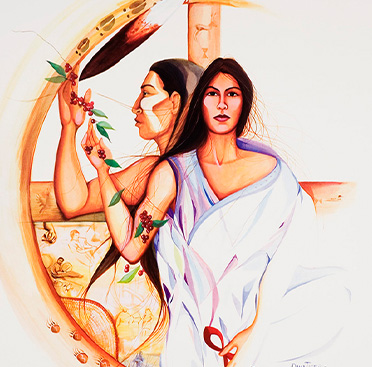

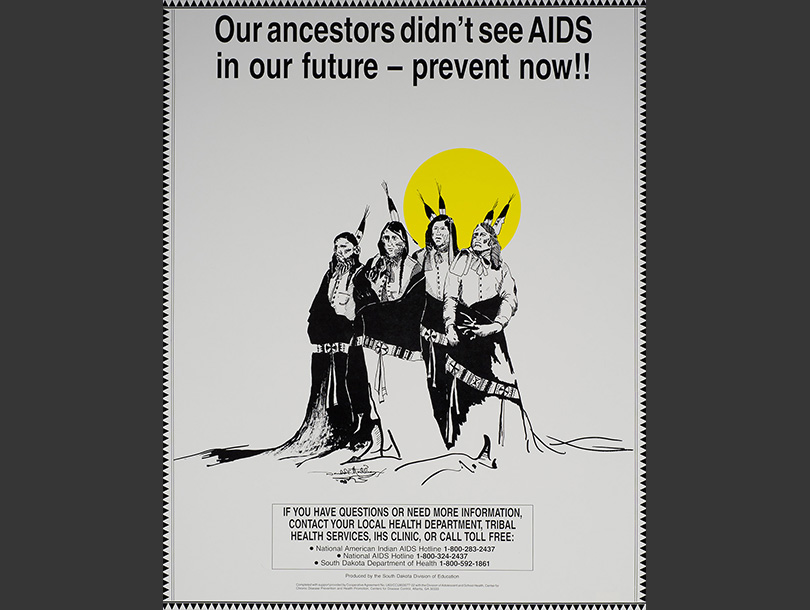

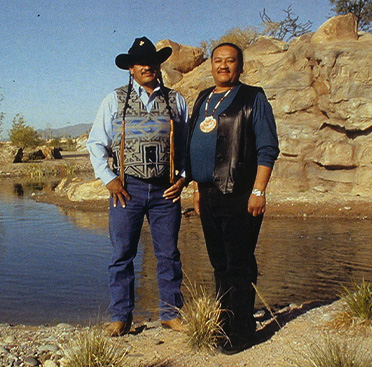

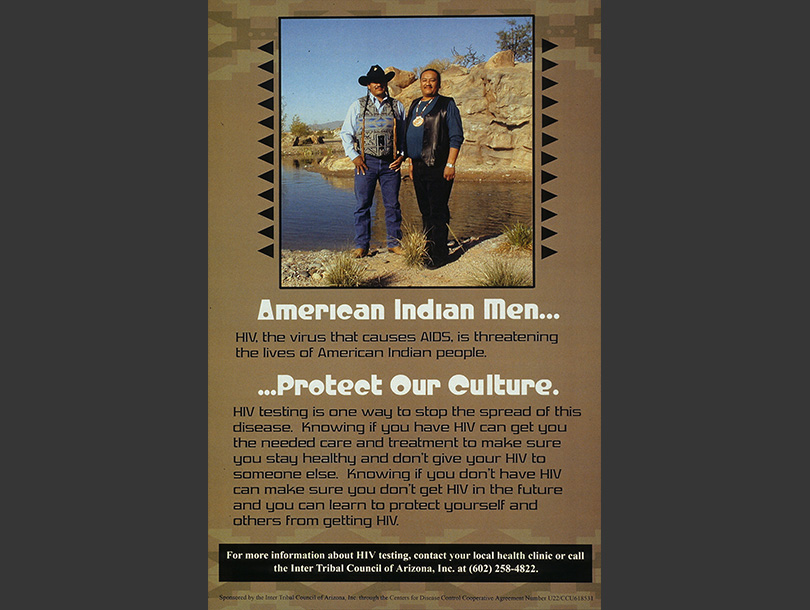

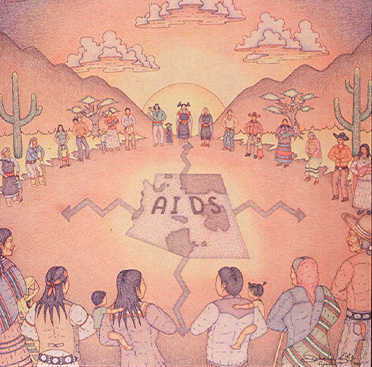

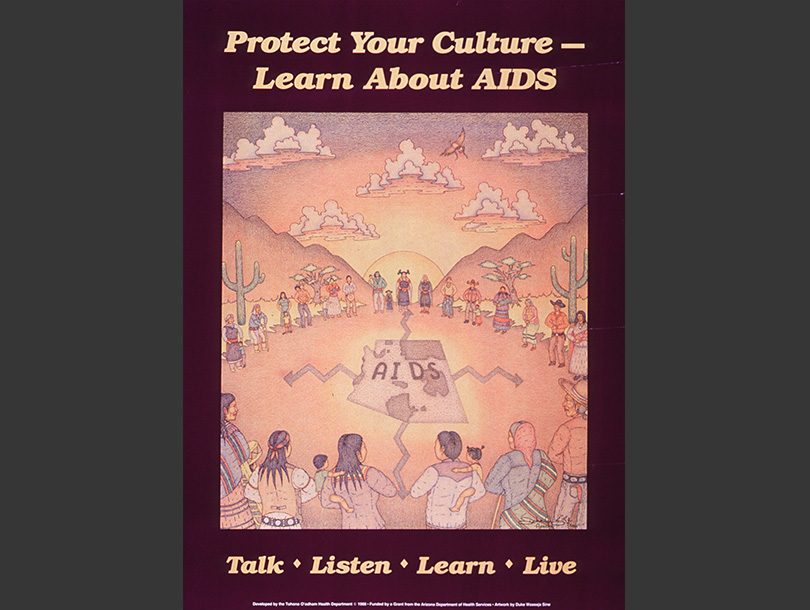

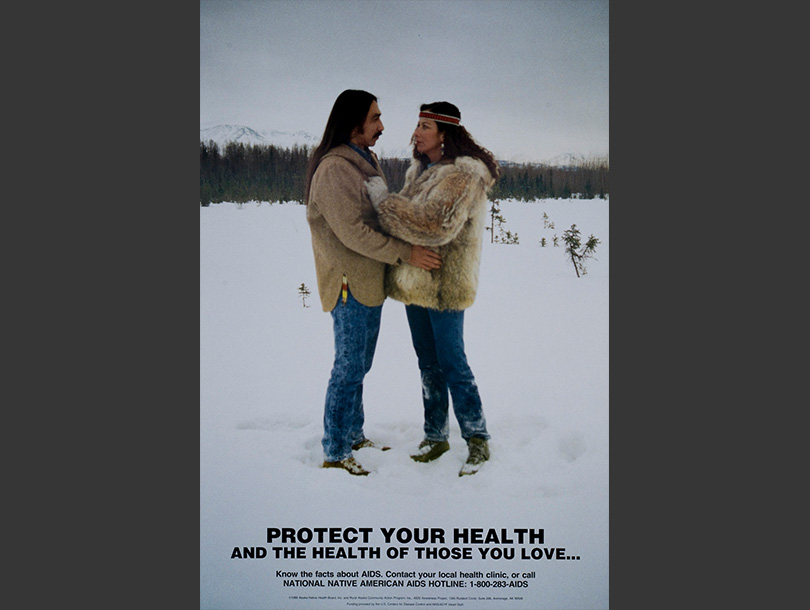

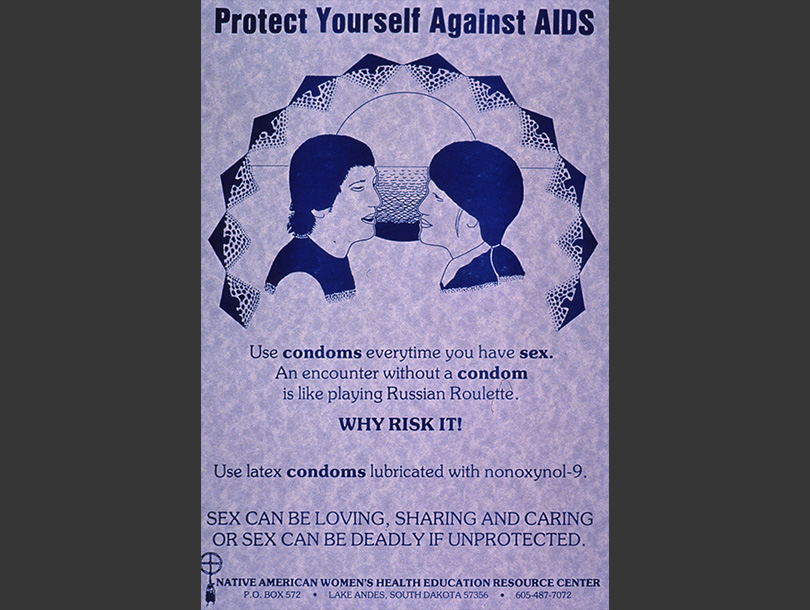

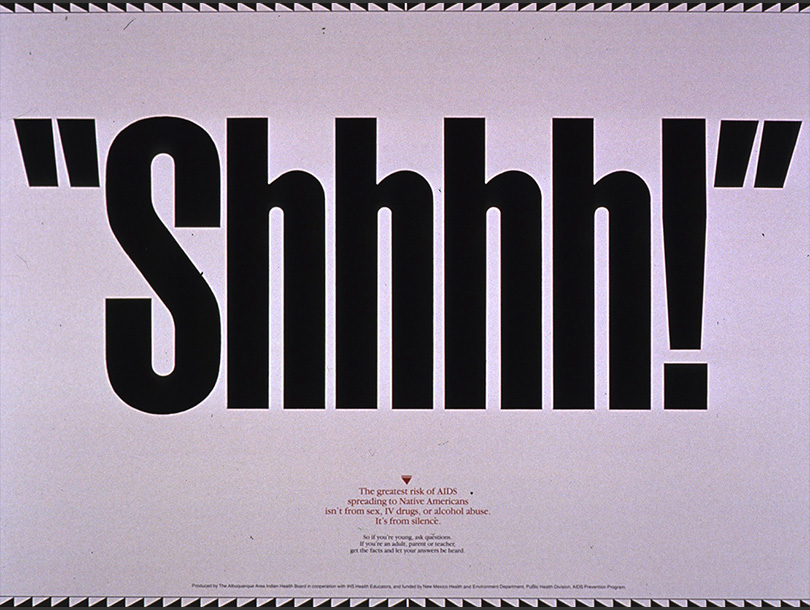

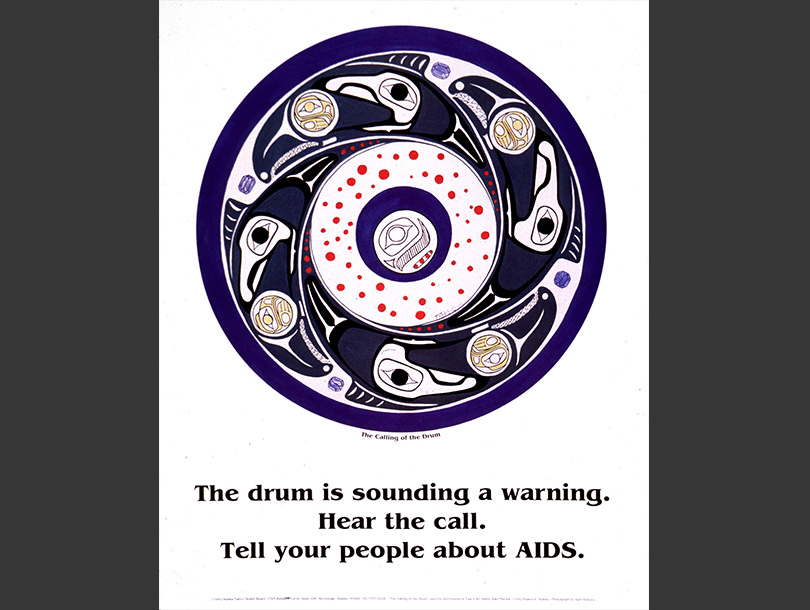

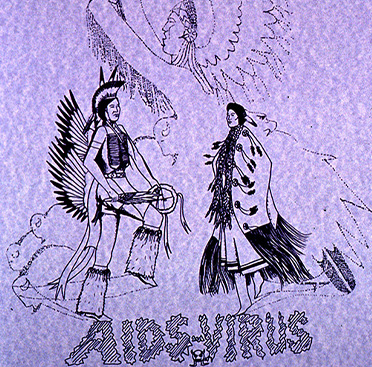

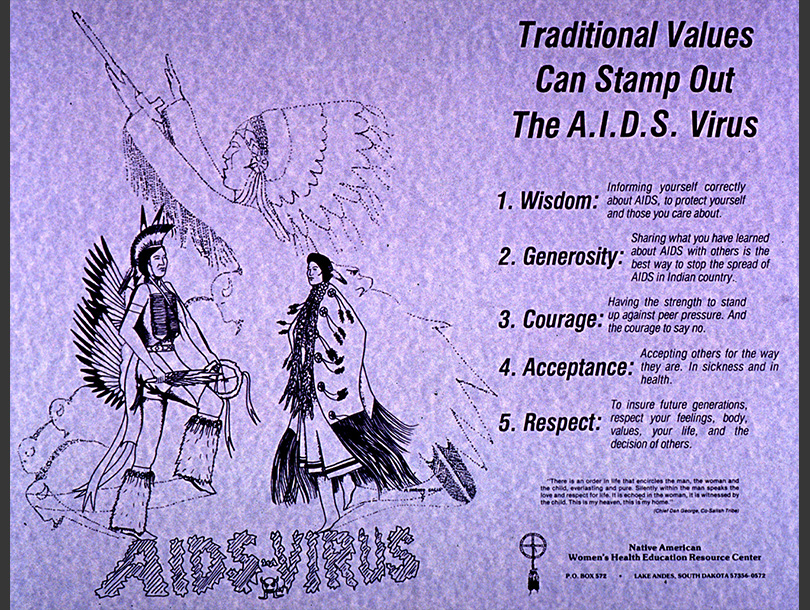

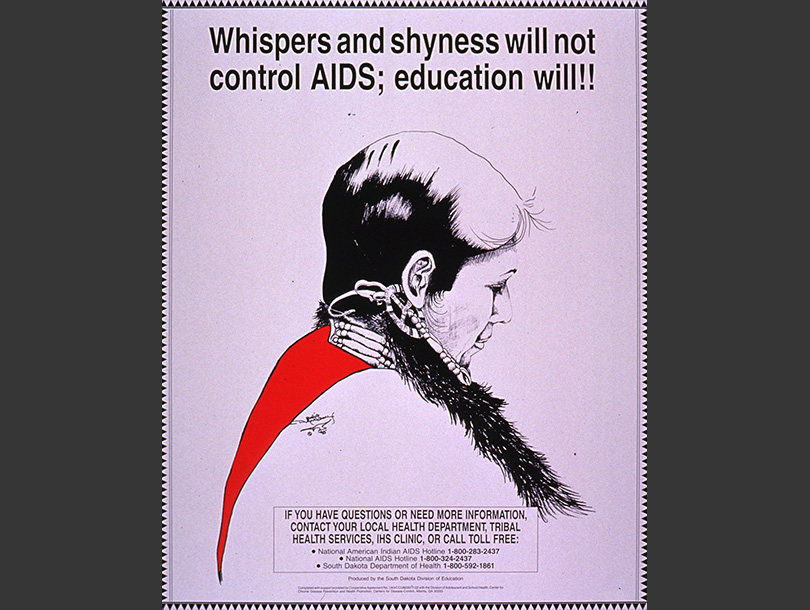

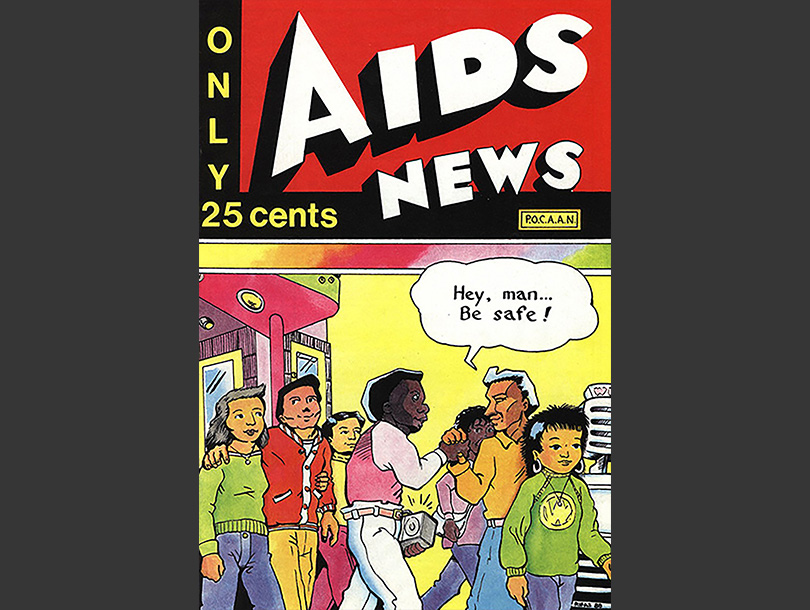

View images in this themeNative Peoples Respond to HIV/AIDS

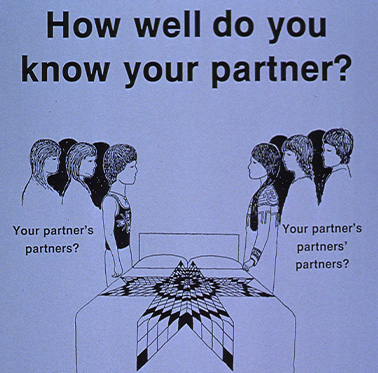

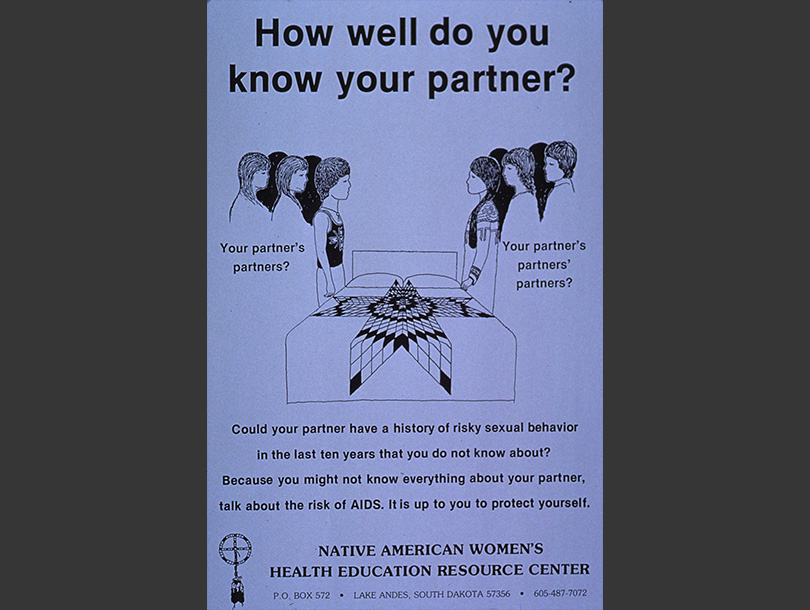

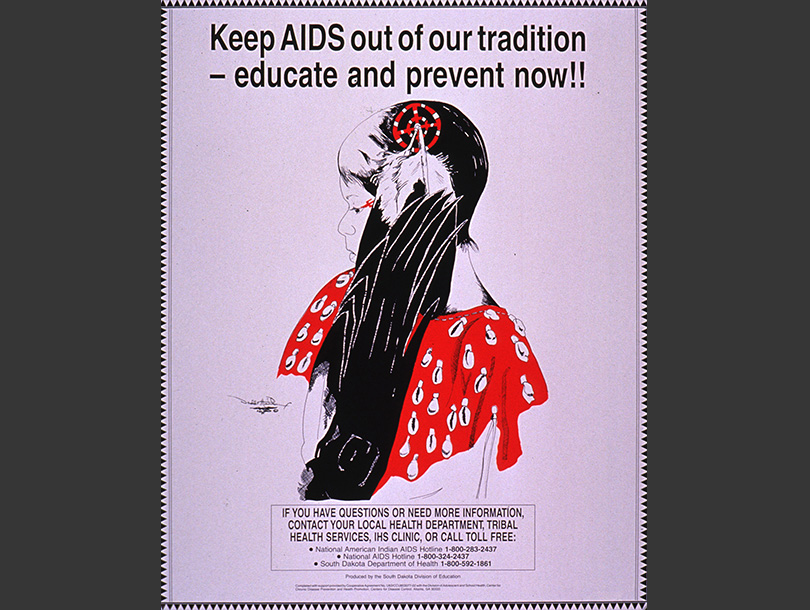

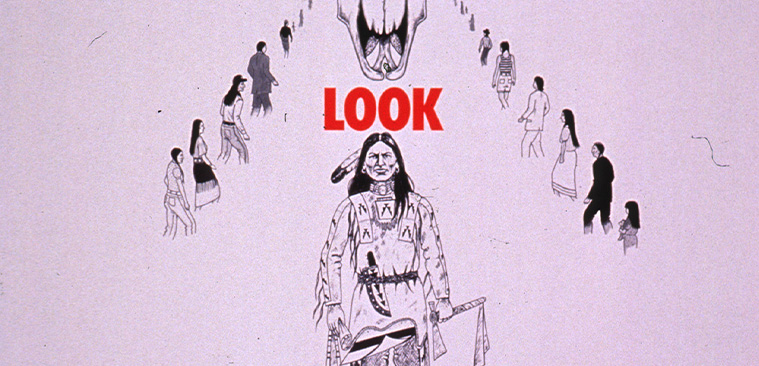

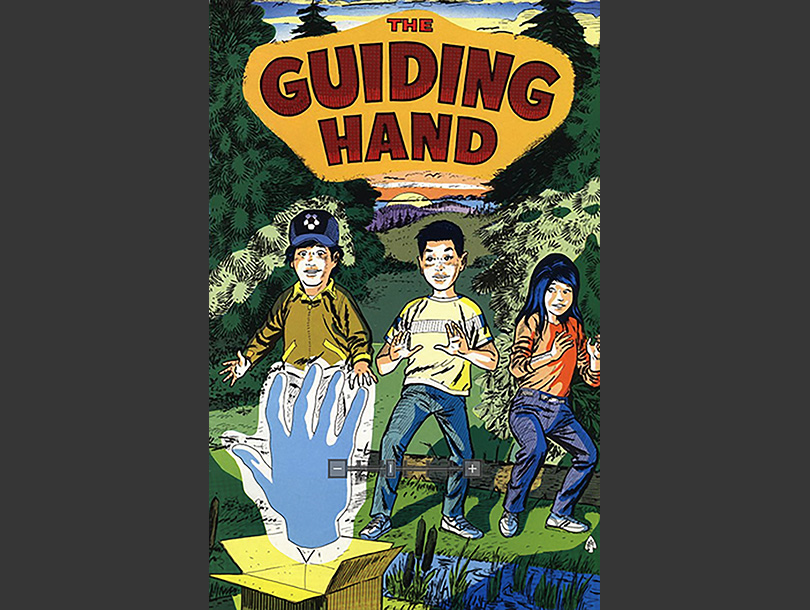

Native peoples continue to be particularly vulnerable to the AIDS crisis due to several factors, including a lack of funding for culturally relevant information, myths and misperceptions about the disease and its causes, and community stigma. Native peoples represent a small percentage of both the United States population and the total number of reported cases of HIV/AIDS, but as a group, they have the third highest rate of diagnosis after African Americans and Latinos. The responses to this disparity have varied.

Since 1987, the National Native American AIDS Prevention Center (NNAAPC) has offered programs and outreach to Native communities. The NNAAPC’s Social Marketing Clearinghouse includes a variety of educational resources, including posters, which have been tailored to individual Native nations in many parts of the country. Many of the posters displayed here reflect the work of tribal governments and local community organizations as they strive to educate their citizens and non-Native neighbors about AIDS. Although not originally focused on HIV/AIDS prevention or awareness, staff at health clinics and support organizations frequently counseled individuals on pursuing safer, healthier behaviors and, in the process, became key participants in fighting the epidemic in Indian Country. The images here reflect an array of culturally— and oftentimes tribally-specific messages aimed at a broad, new audience that required help and information.

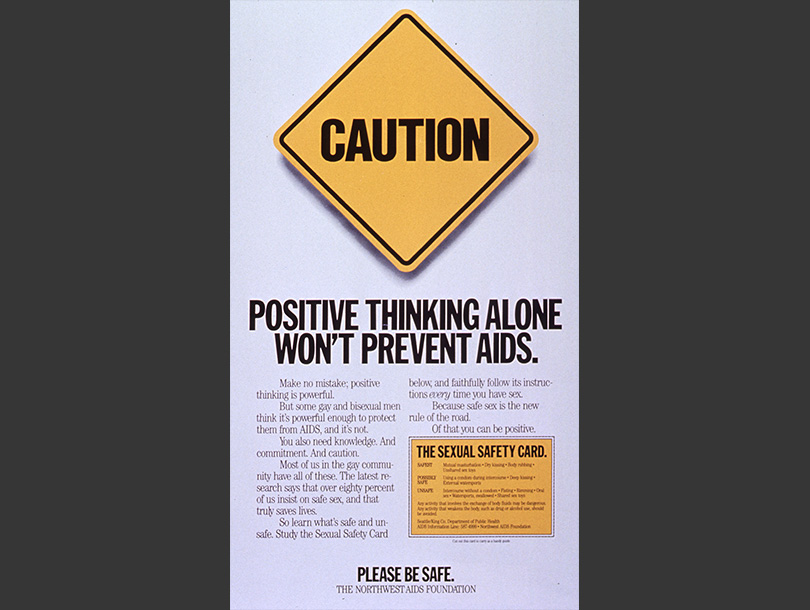

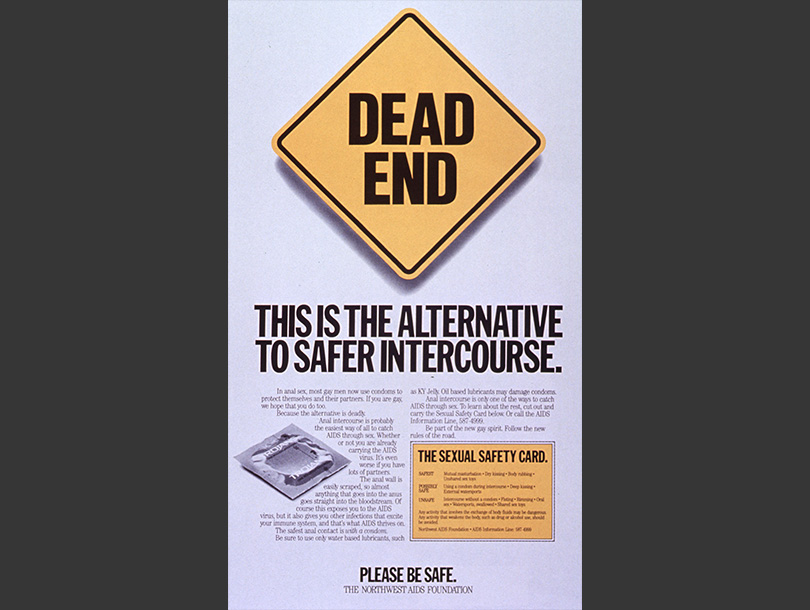

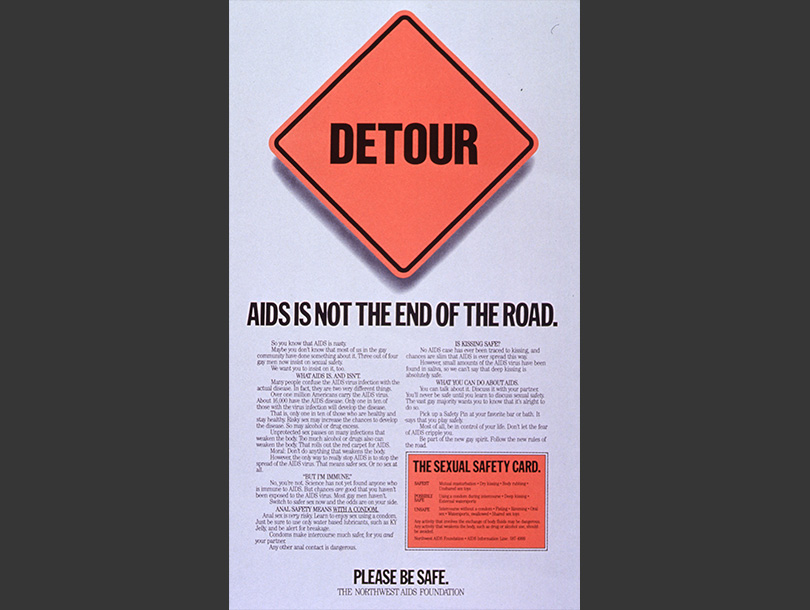

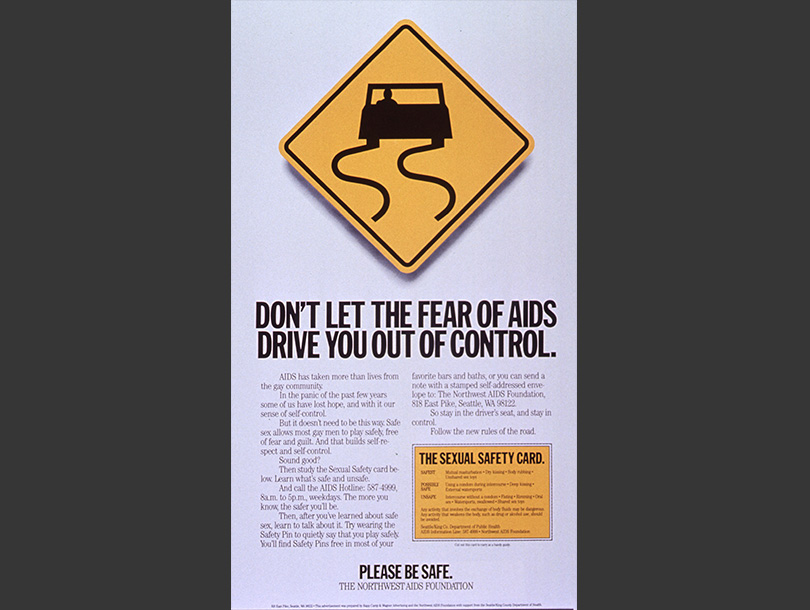

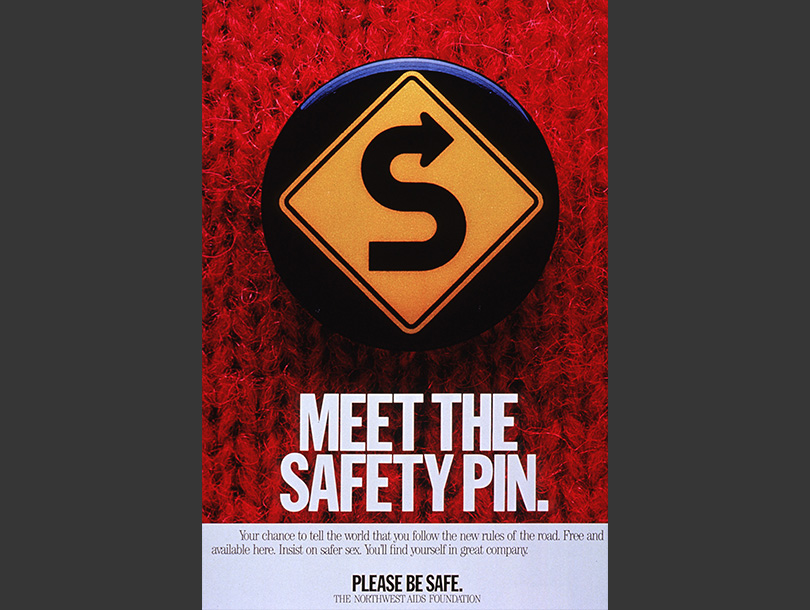

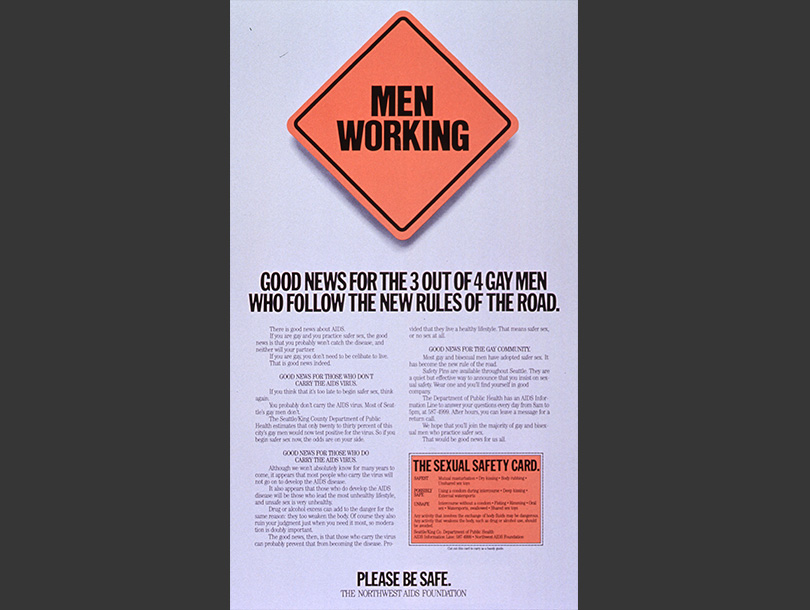

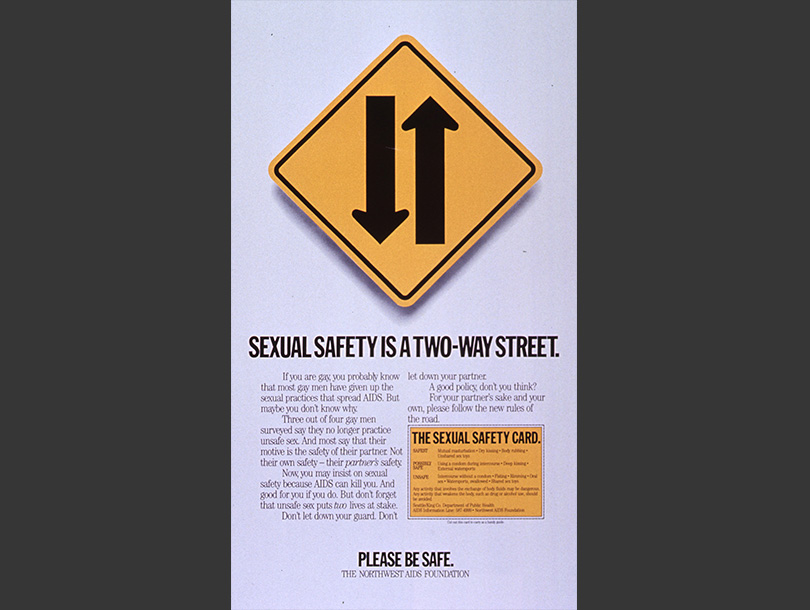

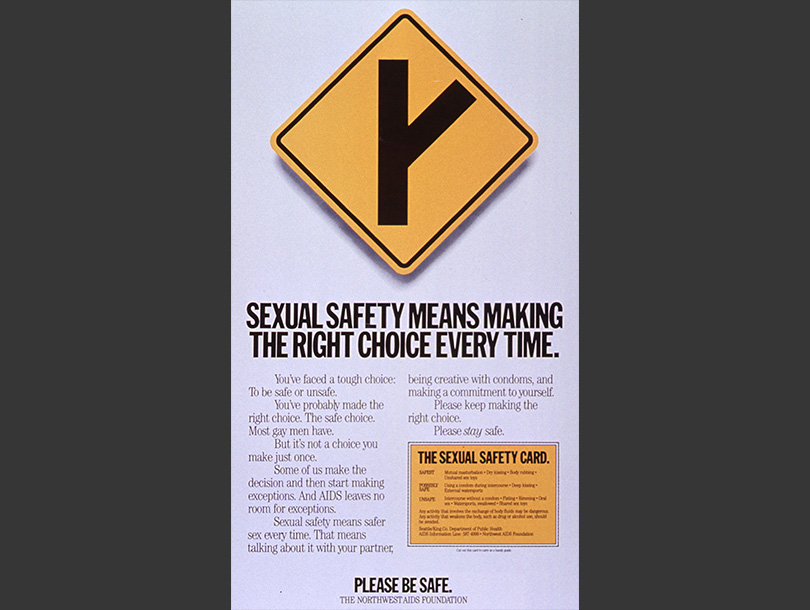

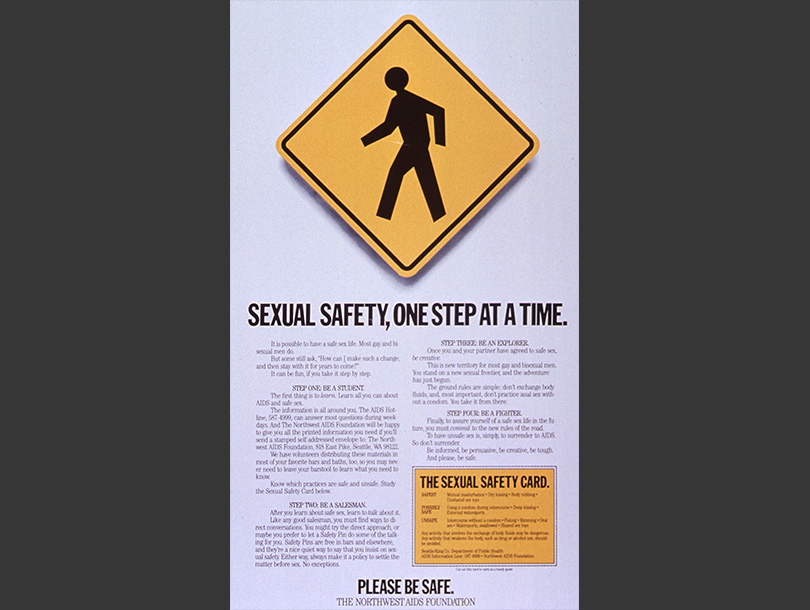

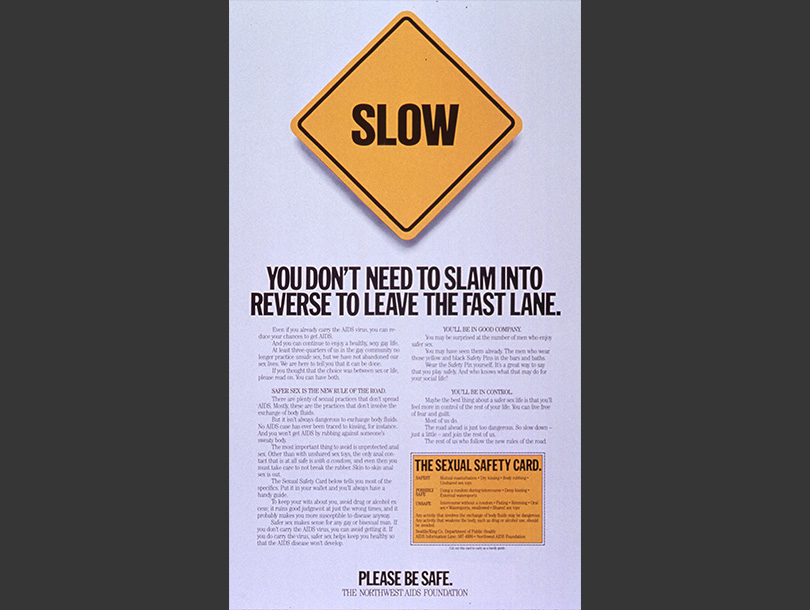

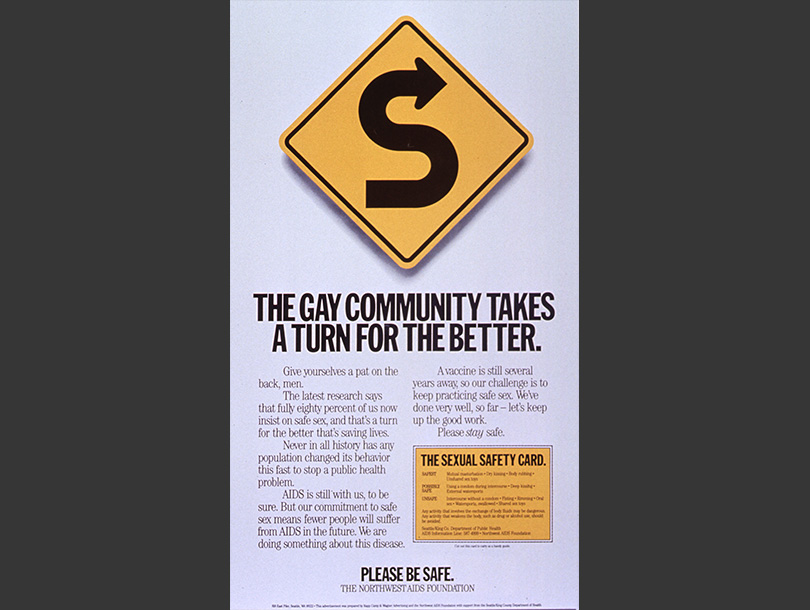

View images in this themePlease Be Safe” by the Northwest AIDS Foundation

In 1987, with funding from the U.S. Conference of Mayors, the Seattle-based Northwest AIDS Foundation launched the “Please Be Safe” campaign to help gay and bisexual men reimagine their sexual behaviors. Using a different creative visual strategy than the sexually charged imagery of some contemporaneous public health efforts, this campaign used road signs—a straightforward, familiar set of symbols—to discuss and advertise sexual safety. The “Please be Safe” or “Rules of the Road” campaign used road signs and compelling, straightforward, community-specific language to help gay men engage in safer sex. The campaign sought to establish these practices as the new norm for all. The “Sexual Safety Card” featured on many of the posters provided quick and accessible information on activities at every level of safety.

The Northwest AIDS Foundation, in addition to producing public health posters, hosted open discussions of risk, testing processes, sexual health, and provided support for people with AIDS and their loved ones. In 2001, the organization merged with the Chicken Soup Brigade to form the Lifelong AIDS Alliance.

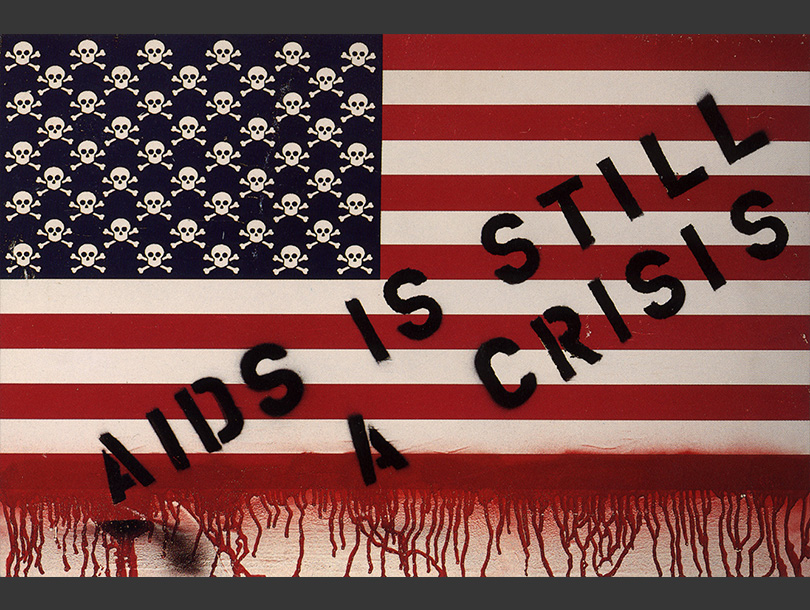

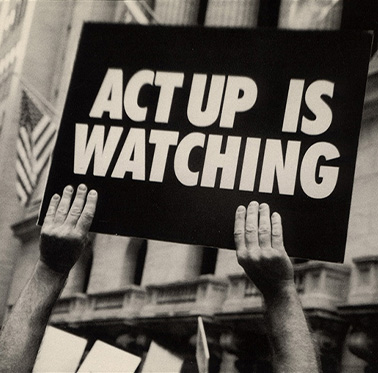

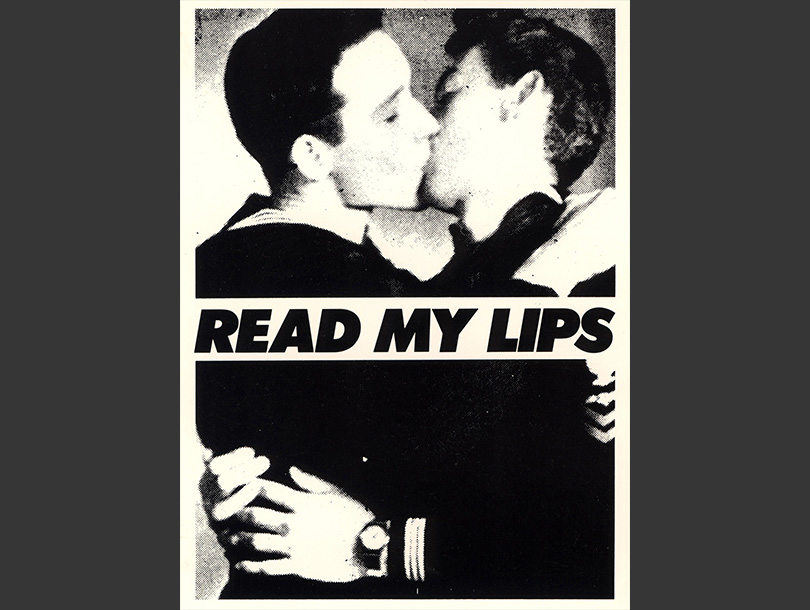

View images in this themePostcard Politics

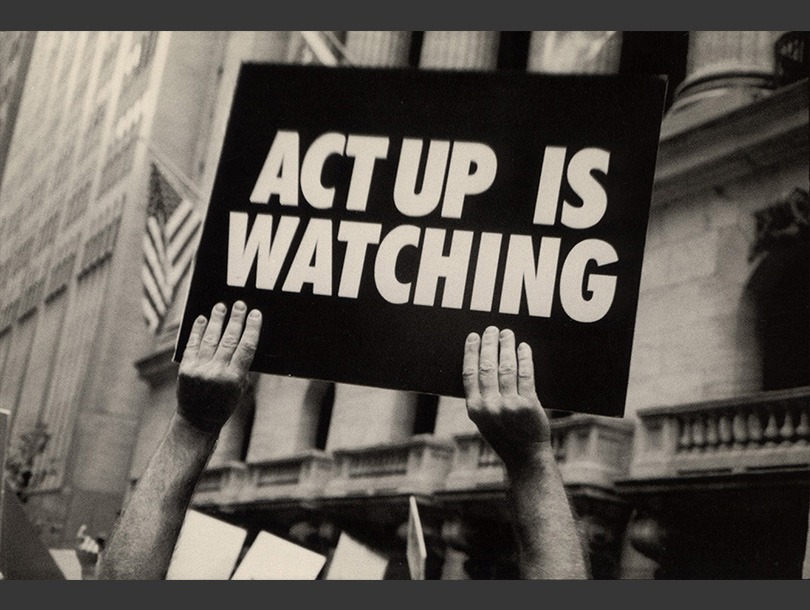

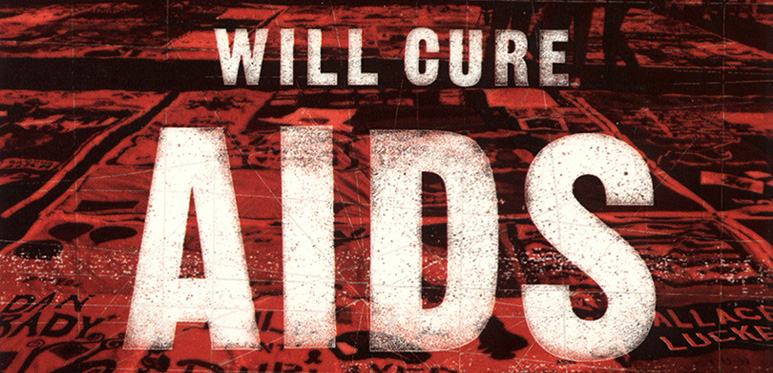

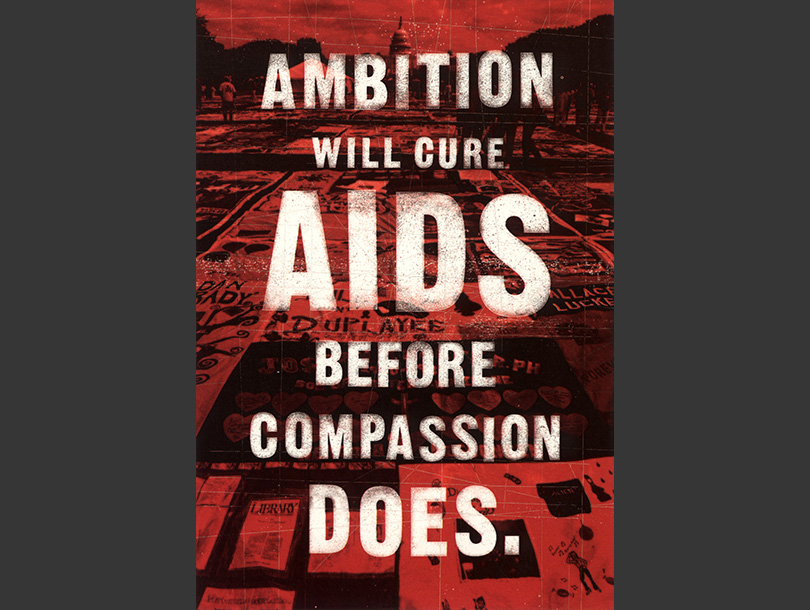

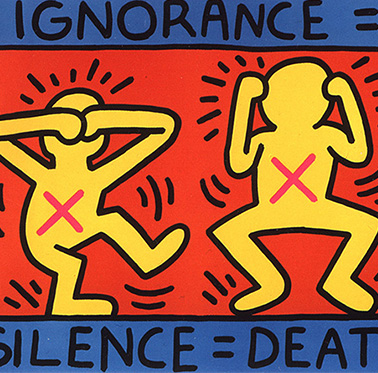

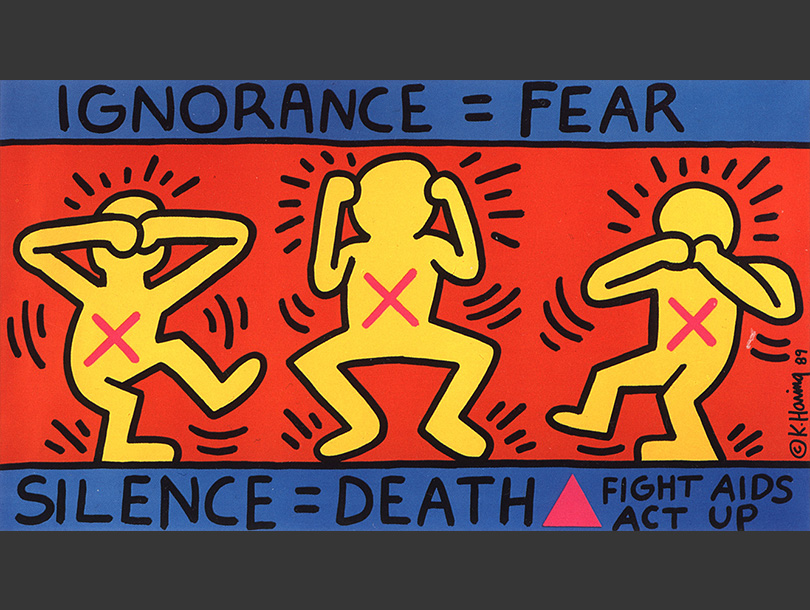

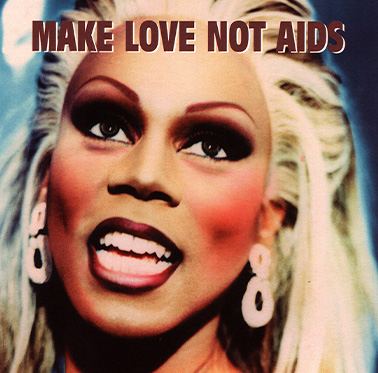

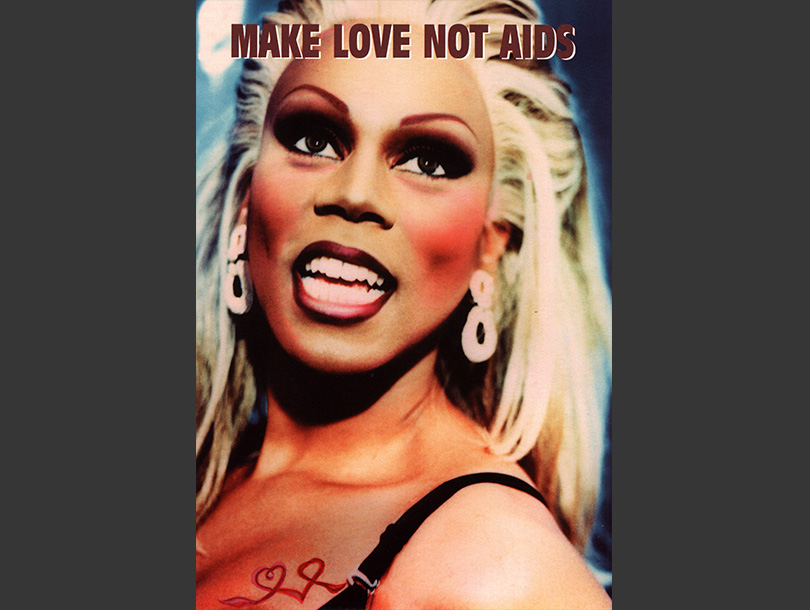

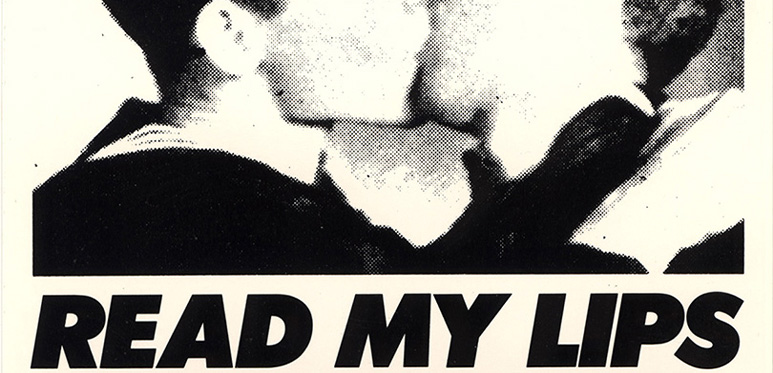

By the mid-1980s, as the AIDS epidemic became a full-on crisis, AIDS activists turned to art and graphic design to illustrate and punctuate their responses to the disease and the resulting social crises. Emerging out of ACT UP’s (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) Gran Fury, a collective of artists who used their talents to fight AIDS, artistic activism insisted that visual culture had tremendous power to affect behavioral and political change. Gran Fury plastered urban neighborhoods with posters featuring arresting and provocative images that forced some to confront their homophobia and others to reimagine what they could do to fight AIDS.

In addition to creating posters, artists reproduced those images as postcards. These small, portable, inexpensive items were visual reminders of how big the AIDS crisis had become. Displayed for the taking at bars, restaurants, neighborhood shops, and community centers, these postcards allowed activists, including those who never joined Gran Fury, to reach an even wider audience.

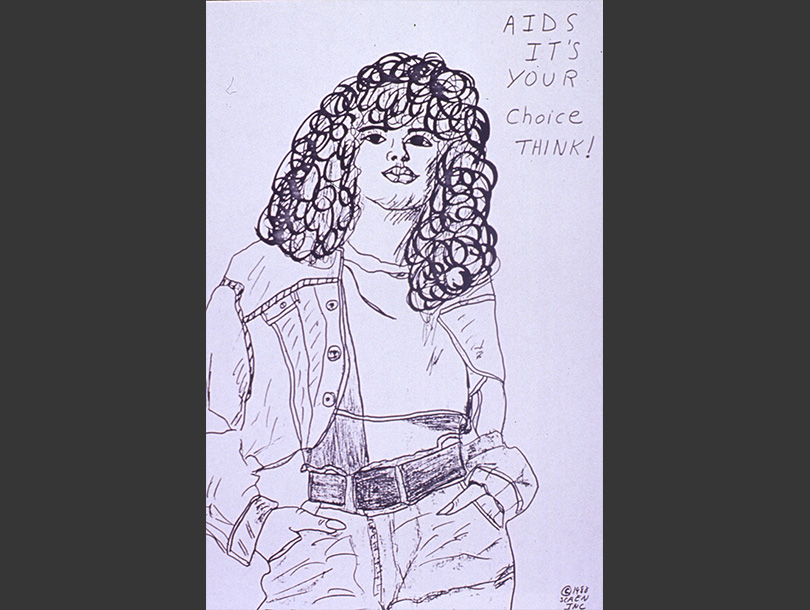

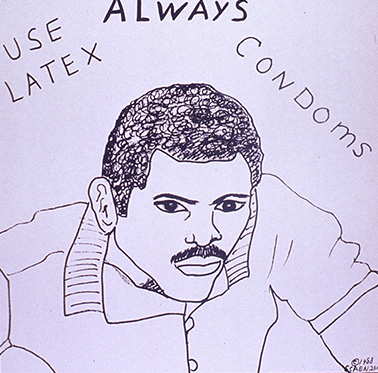

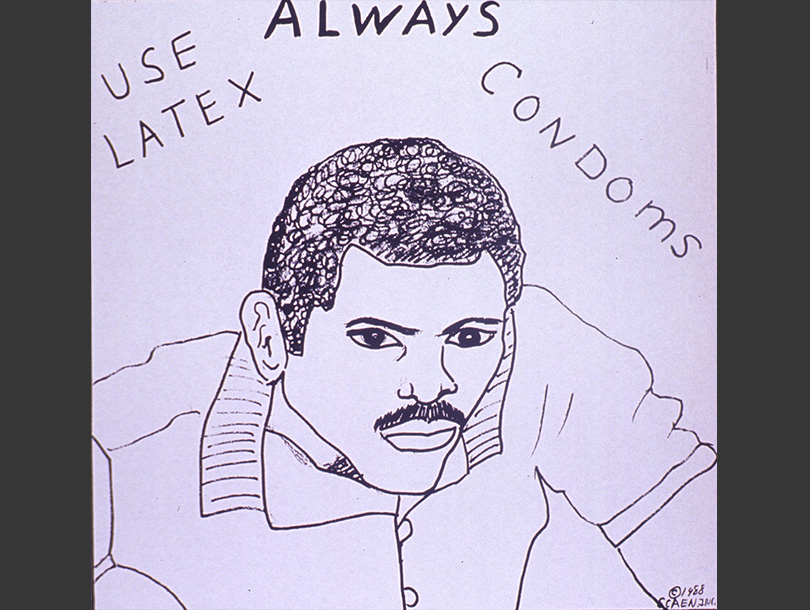

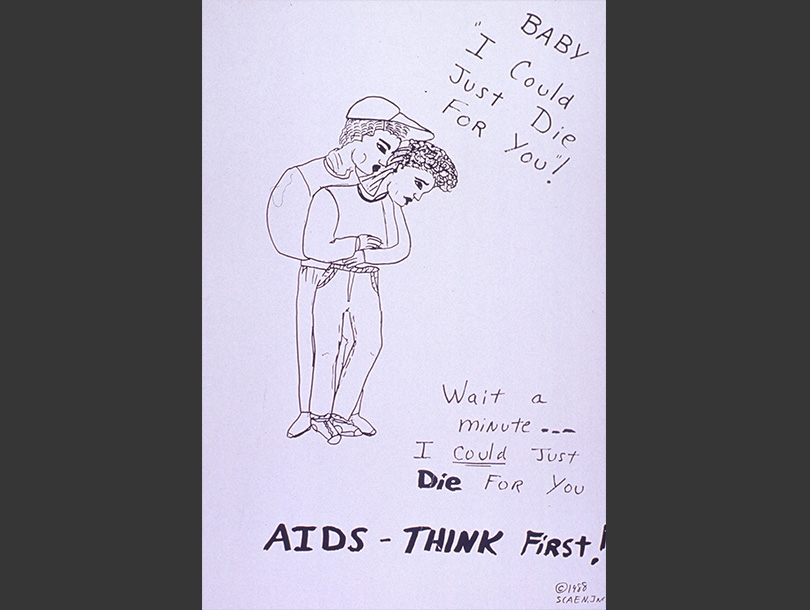

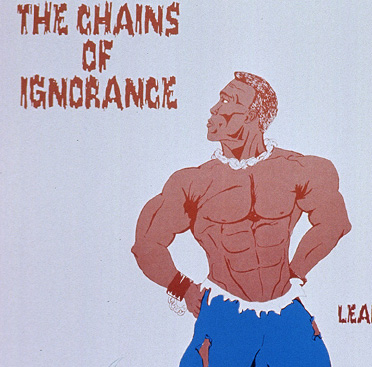

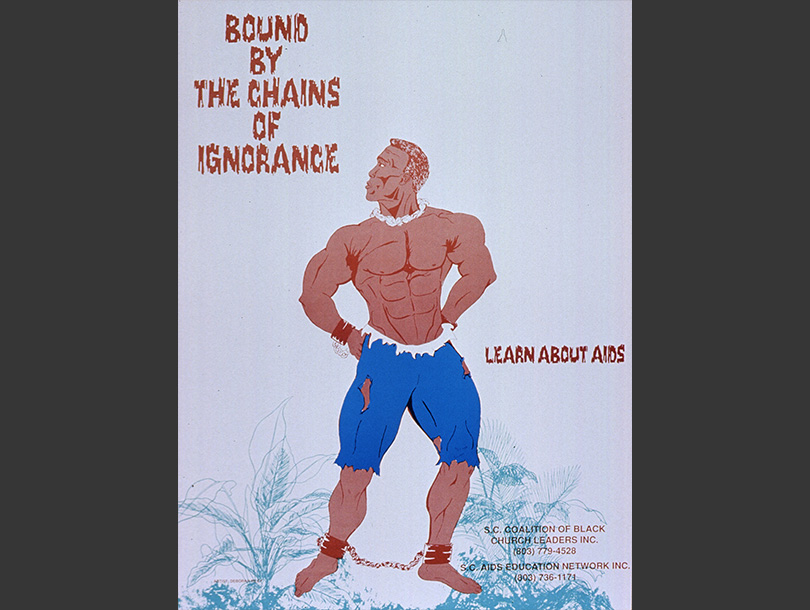

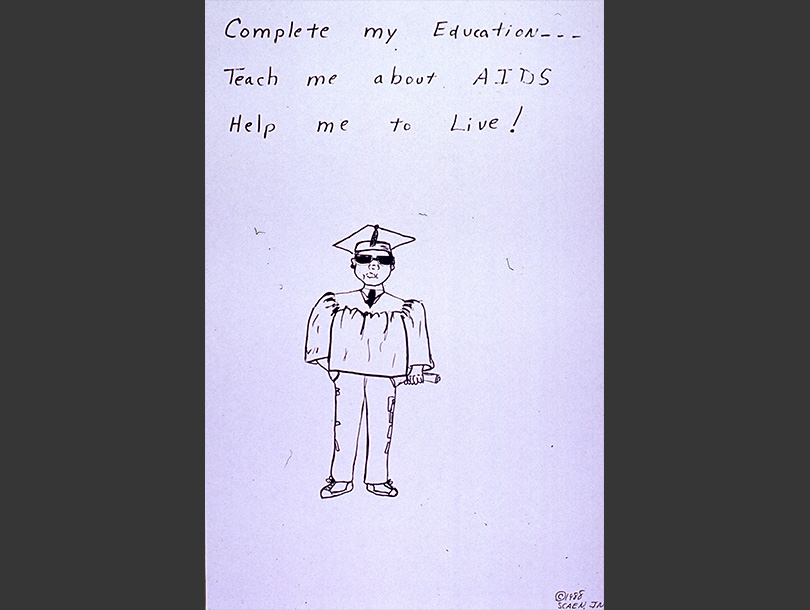

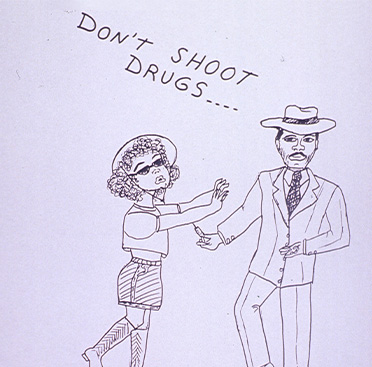

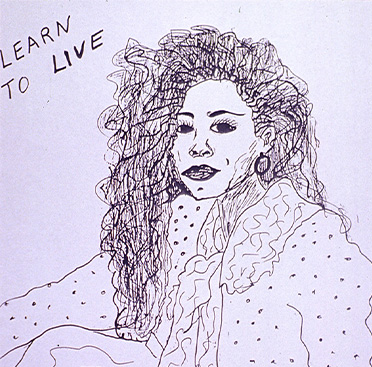

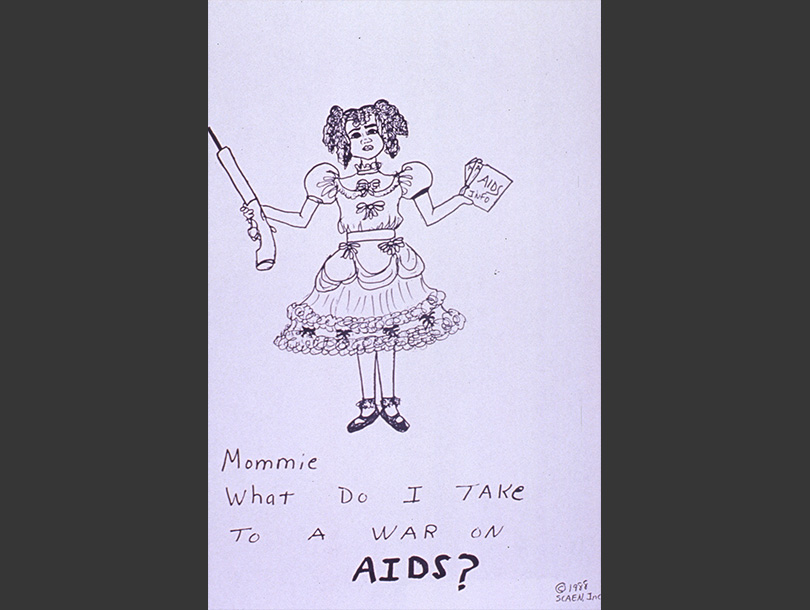

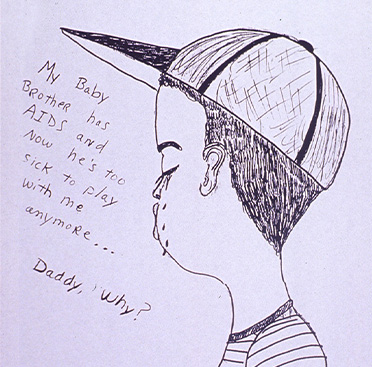

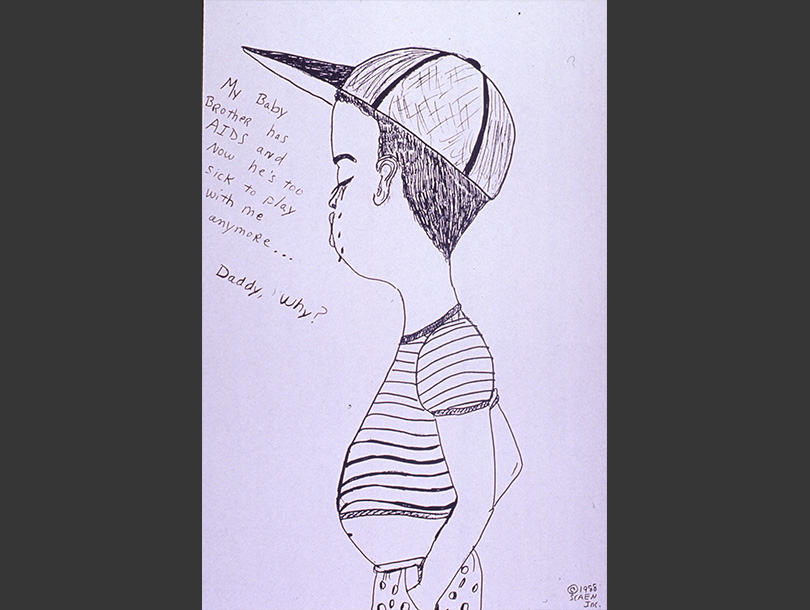

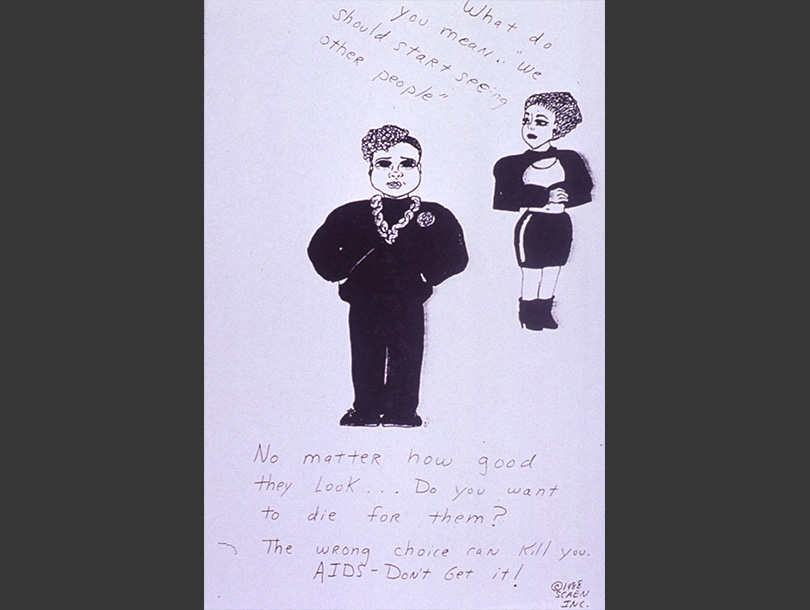

View images in this themeSouth Carolina AIDS Education Network (SCAEN)

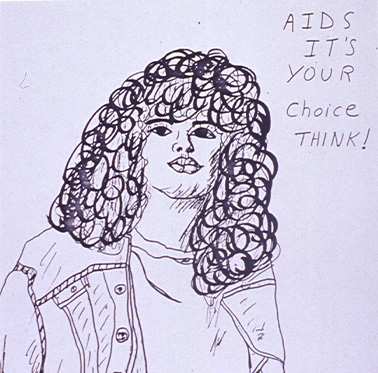

In 1986, DiAna DiAna, an African American hairdresser with a small salon in Columbia, South Carolina, felt compelled to take action when a local newspaper refused to run an advertisement for condoms. DiAna, who had no formal training in public health, began to use her shop as a space to engage customers, mostly African American women, in conversations about why they should care about and practice safer sex. She designed a distribution system to provide free protection—a basket full of gift-wrapped condoms available free to any of the shop’s customers who wanted them. While the artist who drew the posters displayed is unknown, the style typified DiAna's approach to AIDS prevention. DiAna firmly believed in the empowerment of community members so that they saw the epidemic as a problem they could take action.

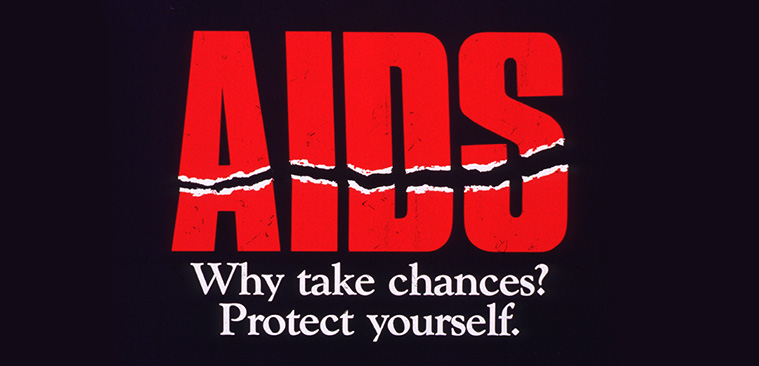

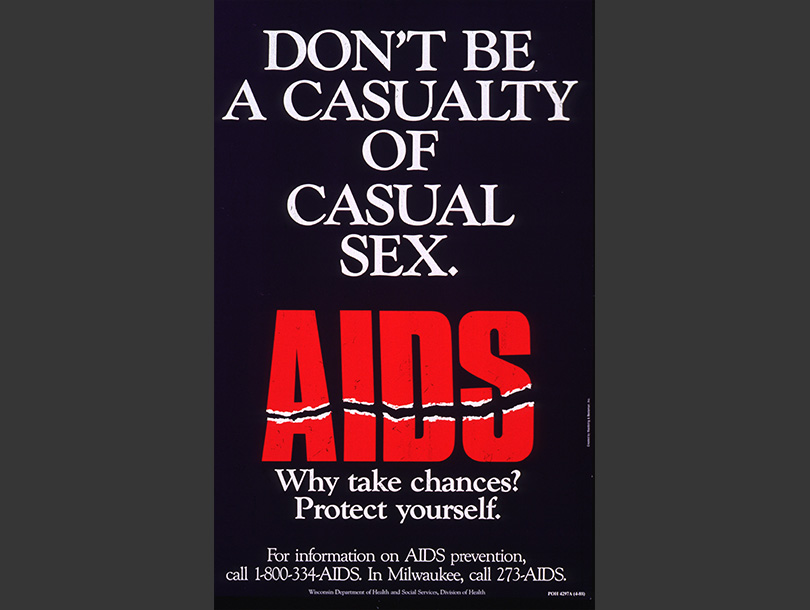

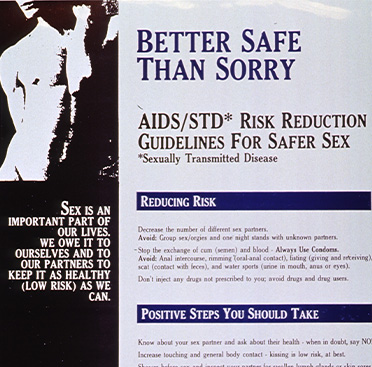

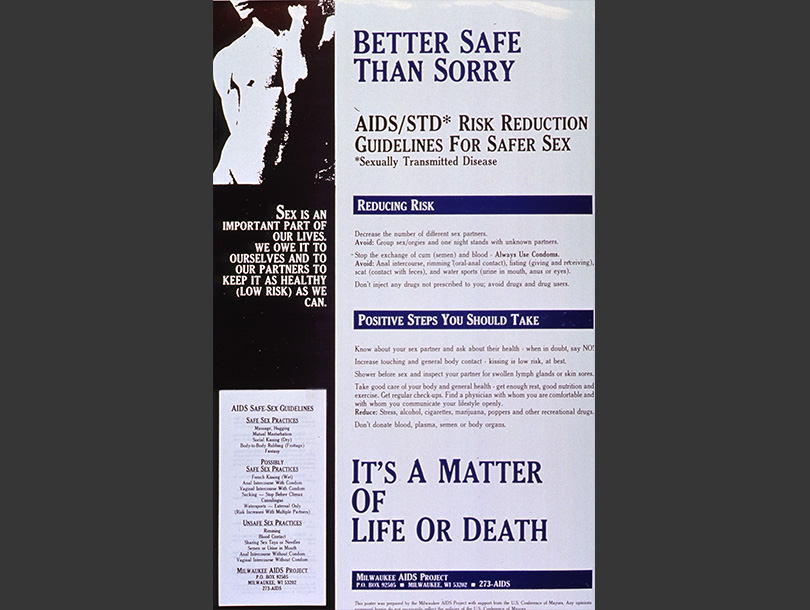

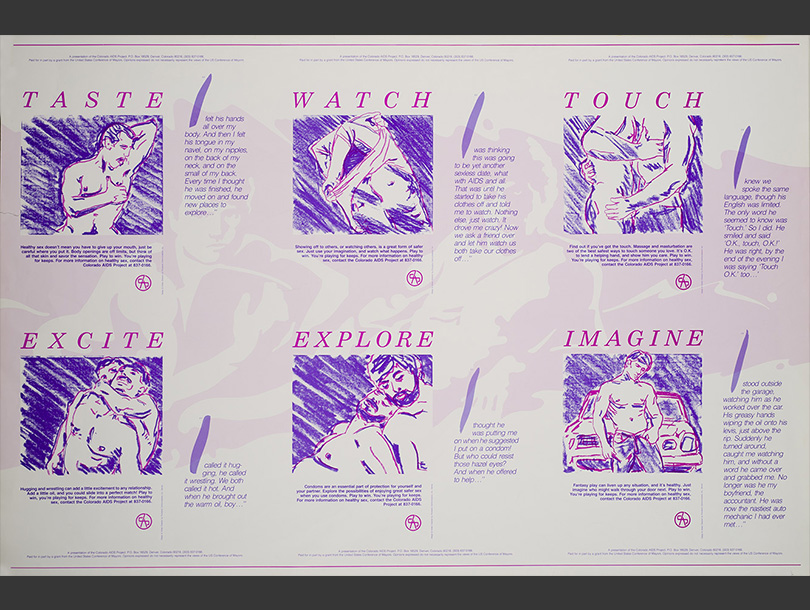

View images in this themeU.S Conference of Mayors and Municipal AIDS Projects

The U.S. Conference of Mayors established an AIDS project in 1984 at the urging of then mayor of San Francisco Dianne Feinstein, the municipal leader of one of the cities most seriously affected by AIDS. From her position at the helm of the city where gays, lesbians, and people with AIDS developed models of care, treatment, and prevention, Feinstein persuaded her fellow mayors to extend San Francisco—style efforts to cities nationwide. This brought much-needed information and support to areas not thought of as gay centers, but nonetheless had growing local AIDS epidemics. Local AIDS projects, including those in Milwaukee and Denver, used the San Francisco model of combining calls for prevention and care to focus on the needs of different populations within their cities and present explicit information about safer sex and intravenous drug use. This was particularly essential after 1987, when the United States government ceased providing federal funding to campaigns deemed supportive of homosexuality and drug use.

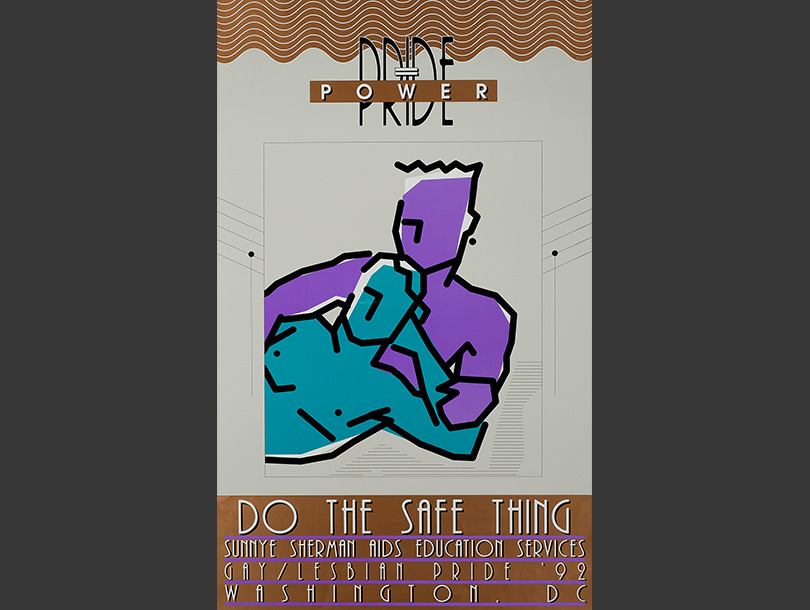

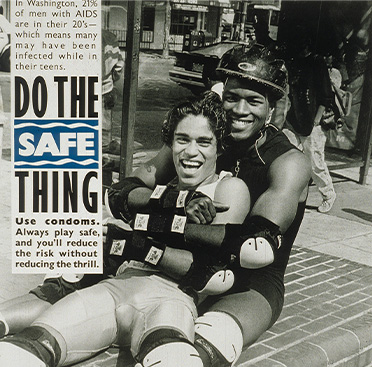

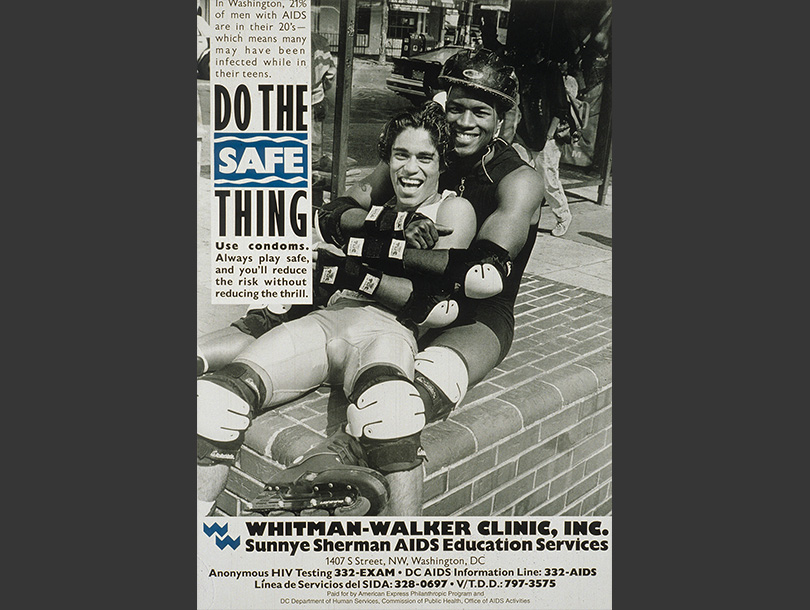

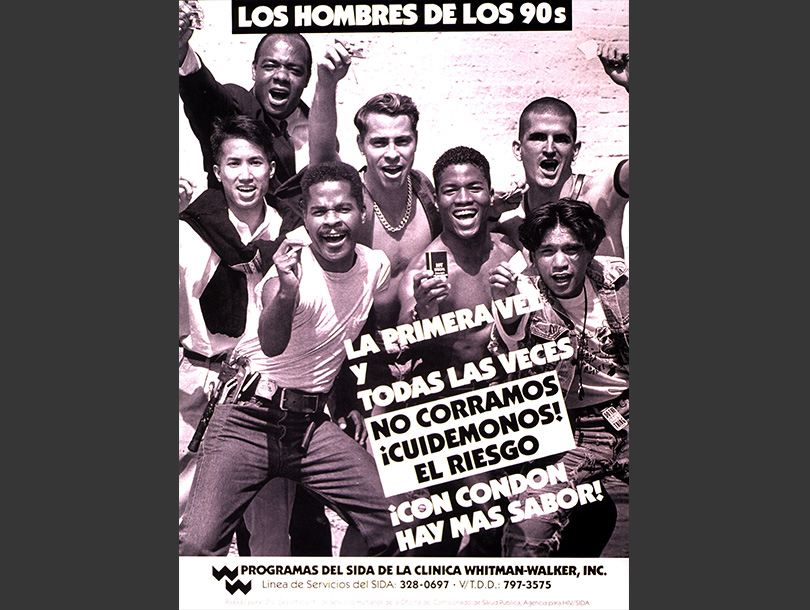

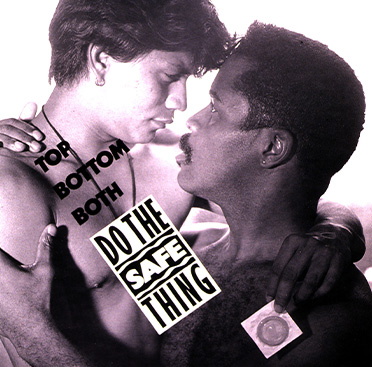

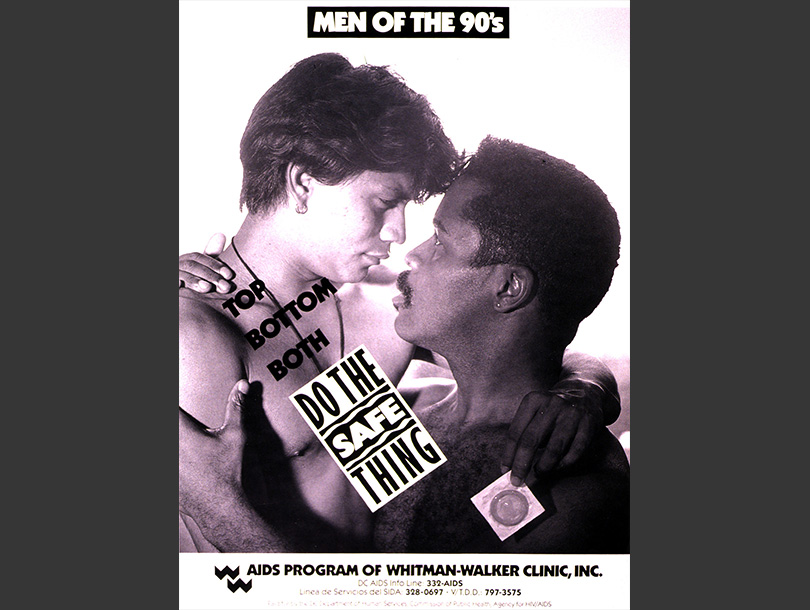

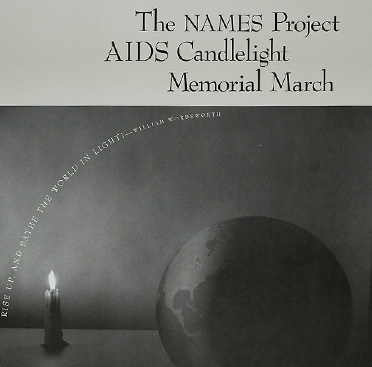

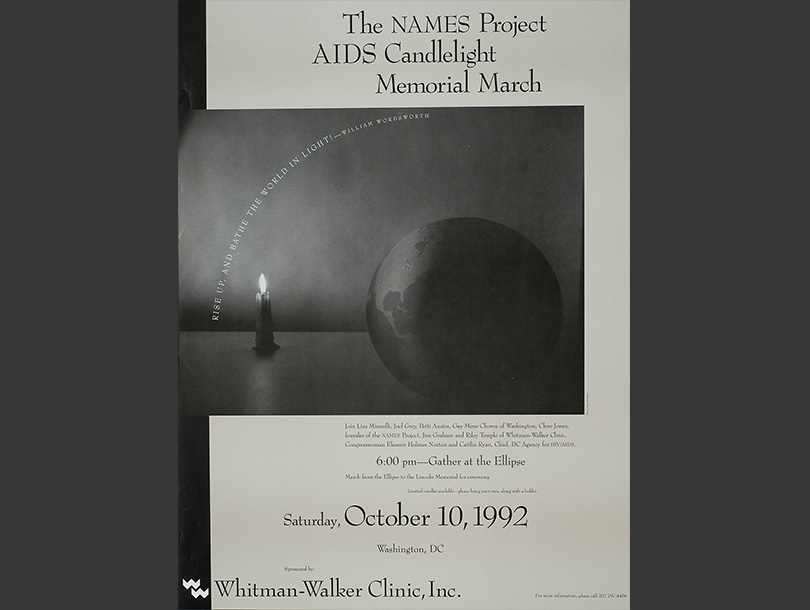

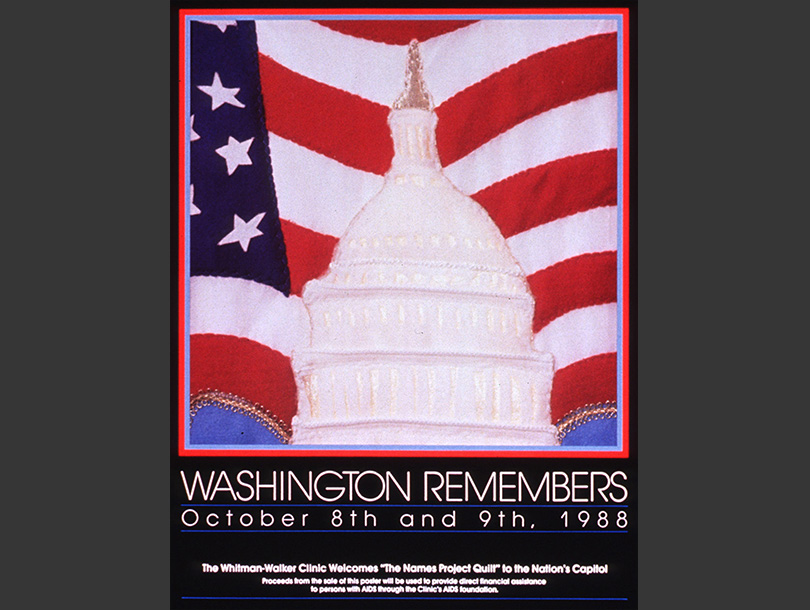

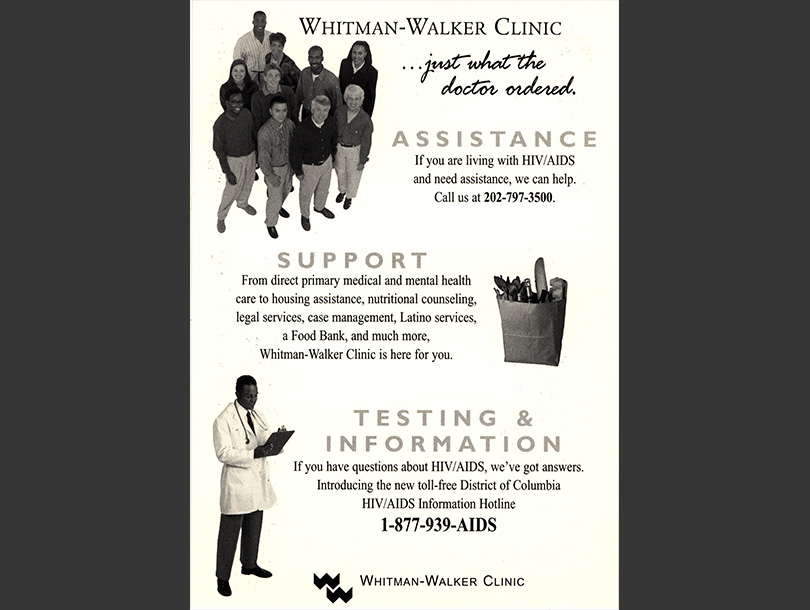

View images in this themeThe Whitman Walker Clinic

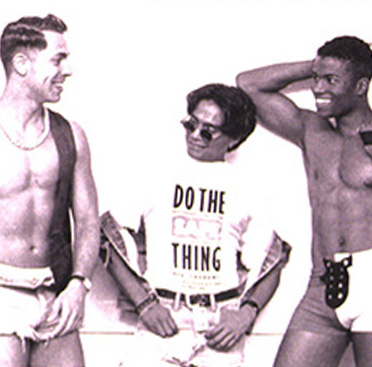

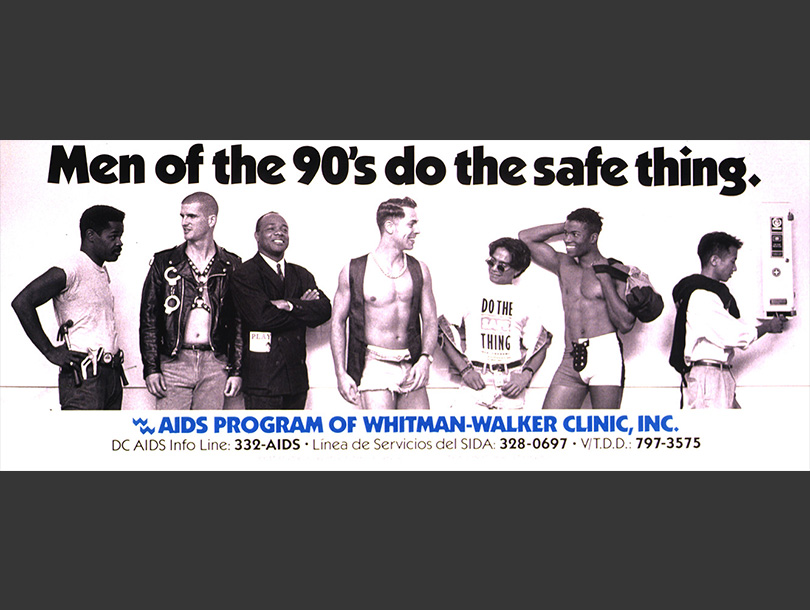

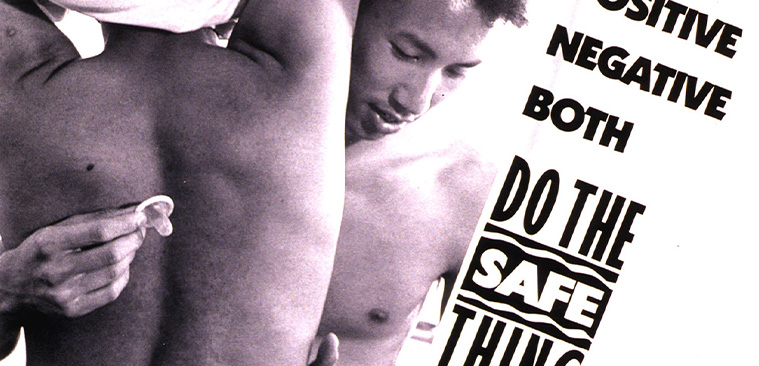

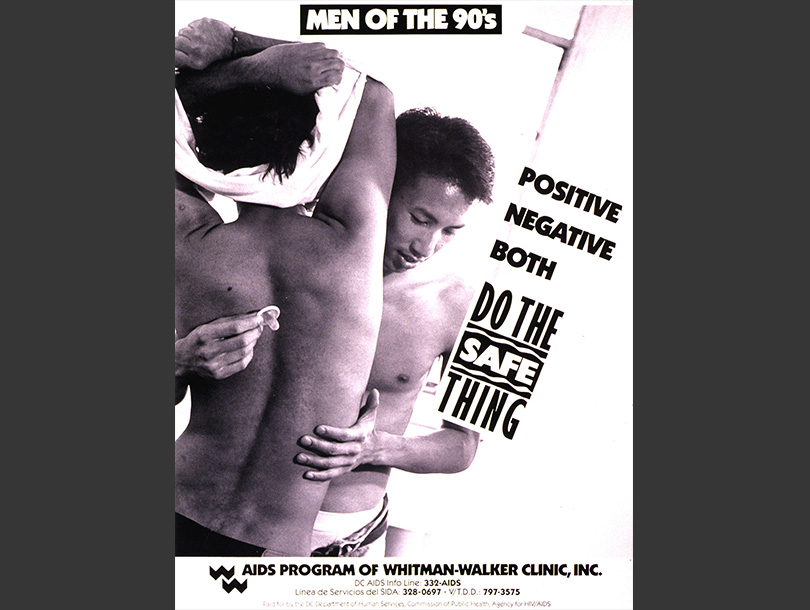

Working in gay communities almost a decade before AIDS appeared in the United States, the Whitman-Walker Clinic was at the frontline of AIDS service prevention in the nation’s capital. Established as part of the Washington Free Clinic and originally named the Gay Men’s VD Clinic, it opened in a church basement in 1973 to provide gay men with unbiased sexual health care. The founders renamed it in 1978 in honor of two people who defied gender and sexual norms of the nineteenth century: Walt Whitman, the famous American poet, who made his life with men, and Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, a feminist activist and medical doctor, who dressed exclusively in men’s clothes and was the only woman to receive the Medal of Honor for her service as a surgeon during the Civil War.

As early as 1983, the clinic staffed the first AIDS hotline in the city, and within two years, it opened multiple homes for people with AIDS who sought refuge and care from the larger gay and lesbian community. In addition to providing much-needed care for people with AIDS and access to treatment, Whitman-Walker was at the forefront of designing and distributing safer-sex materials that targeted a range of audiences. Even as the clinic created campaigns to help all kinds of people, it never forgot to attend specifically to the needs of men who had sex with men.

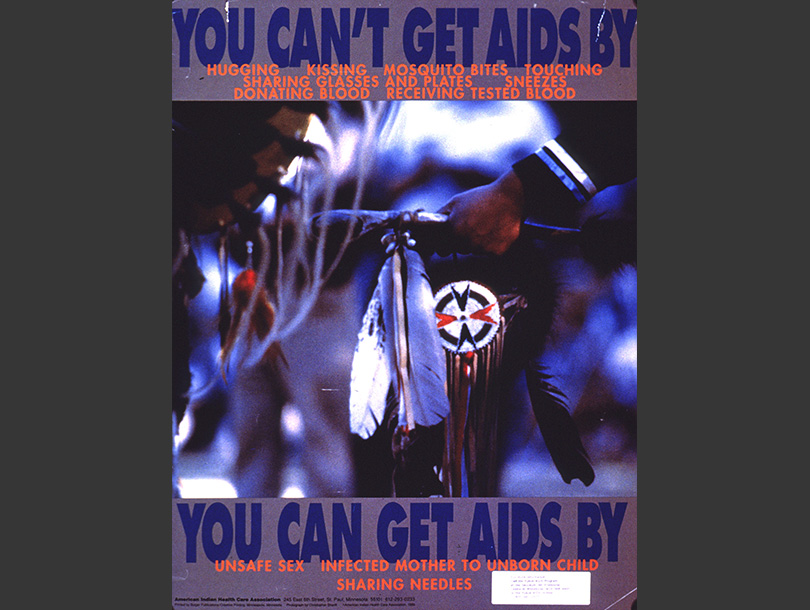

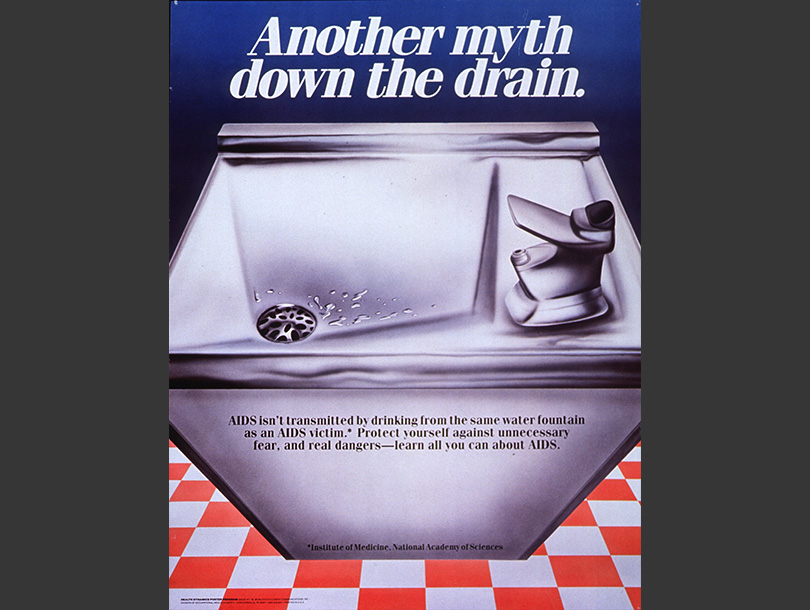

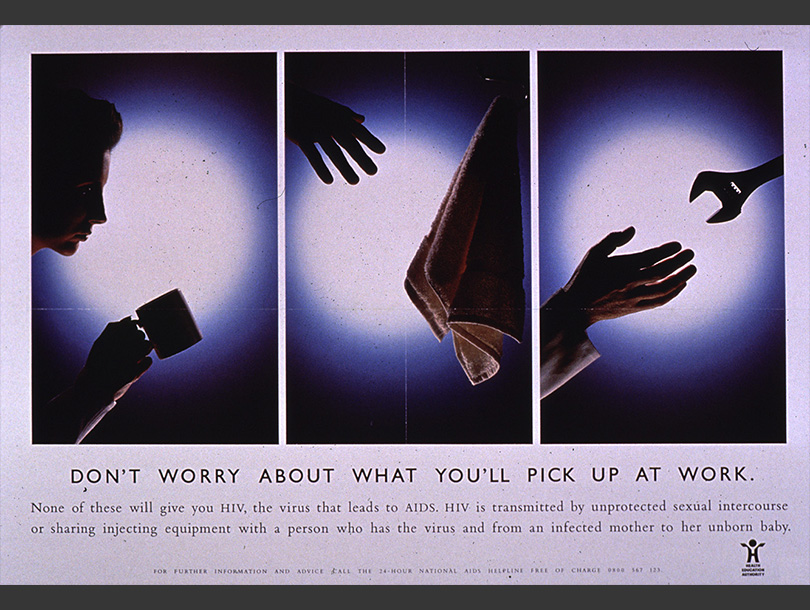

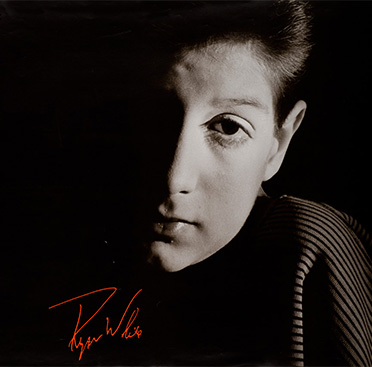

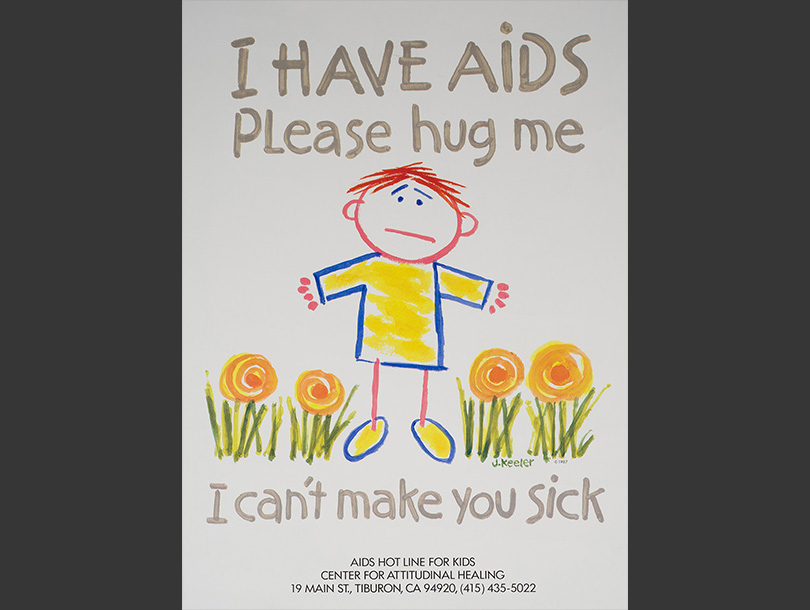

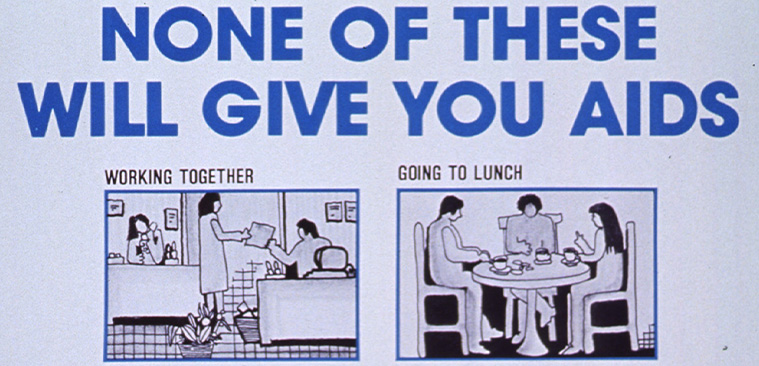

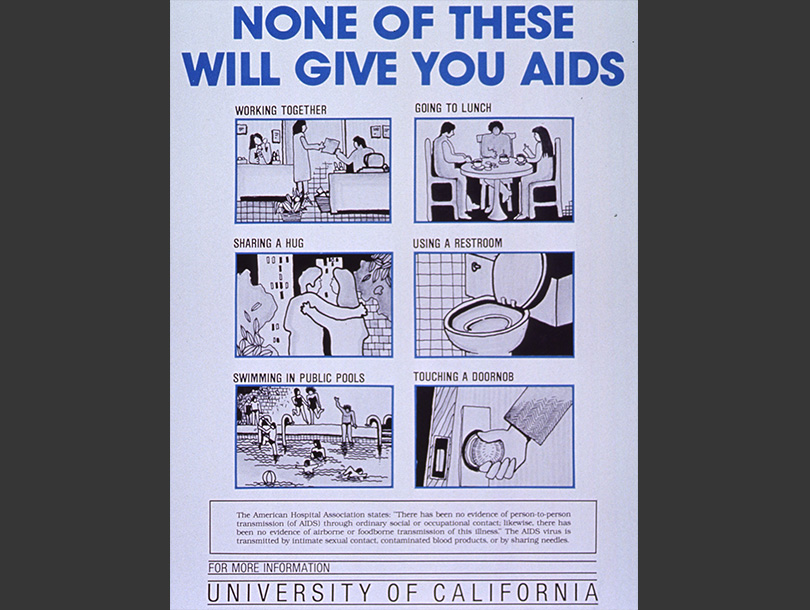

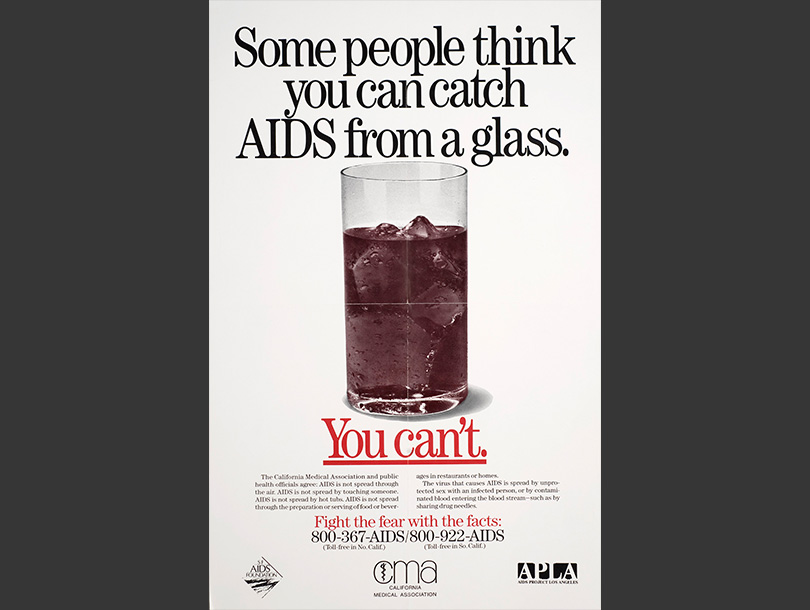

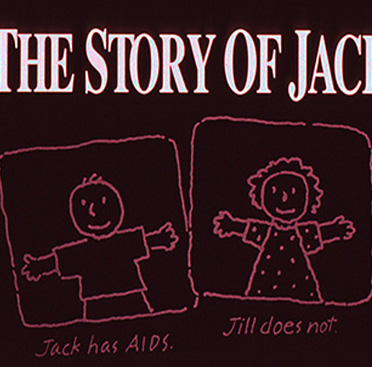

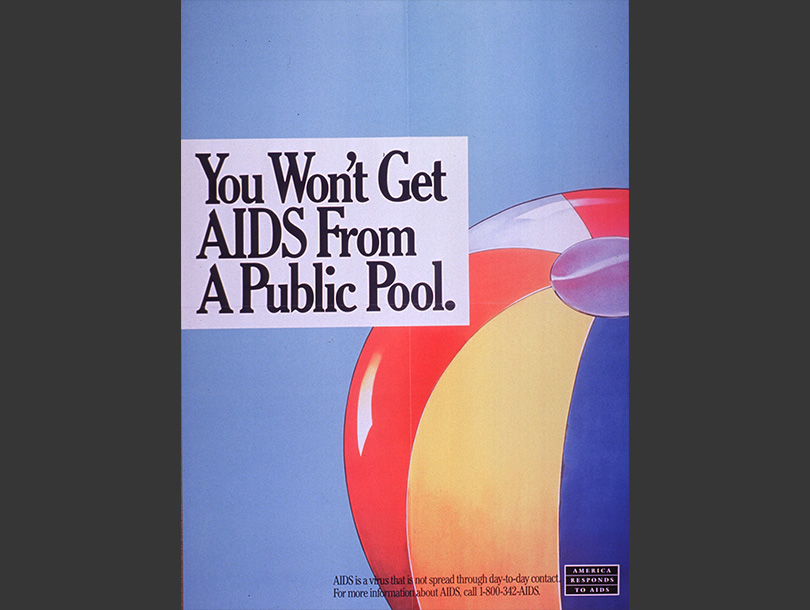

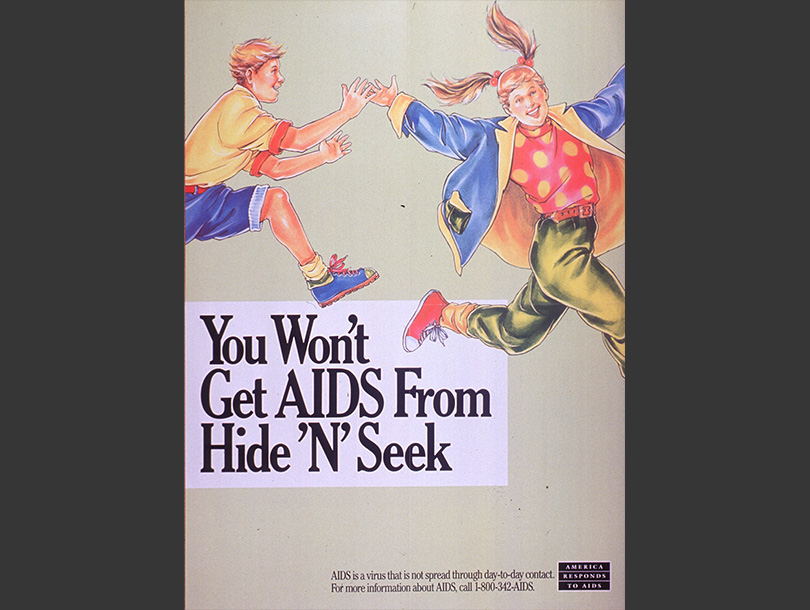

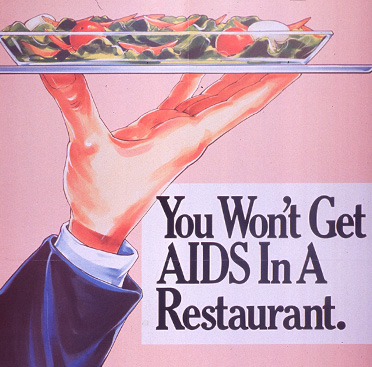

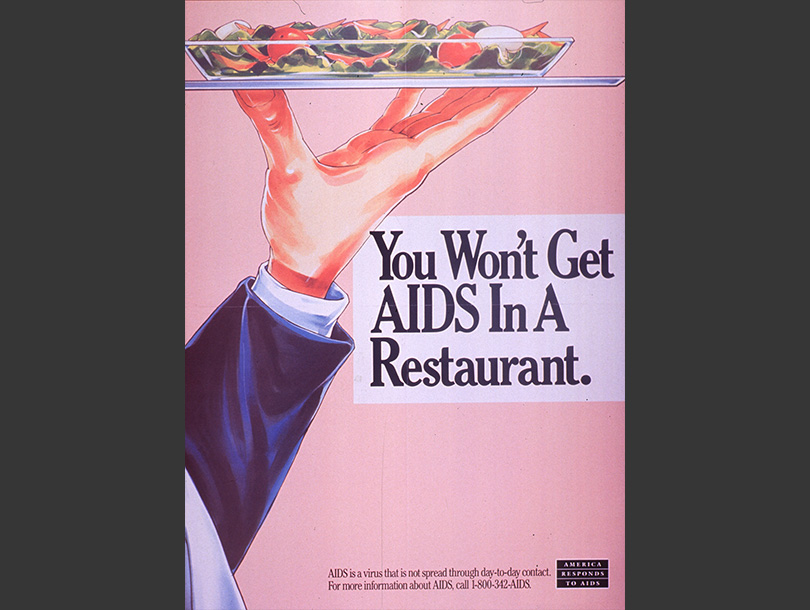

View images in this themeYou Can’t Get AIDS From…

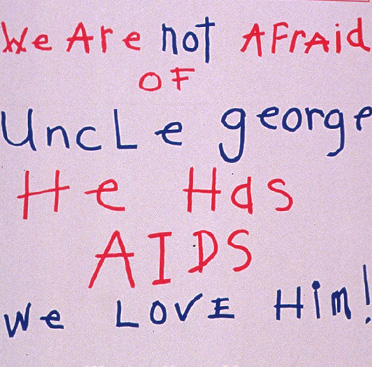

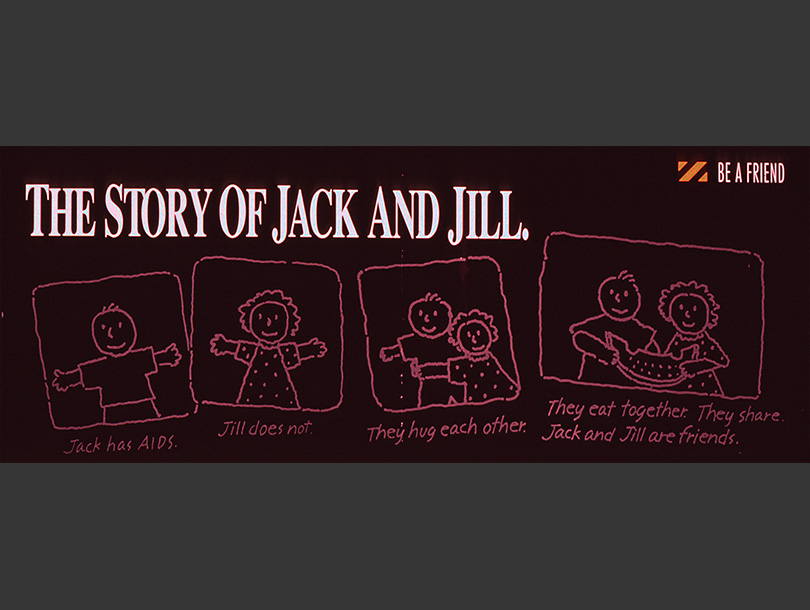

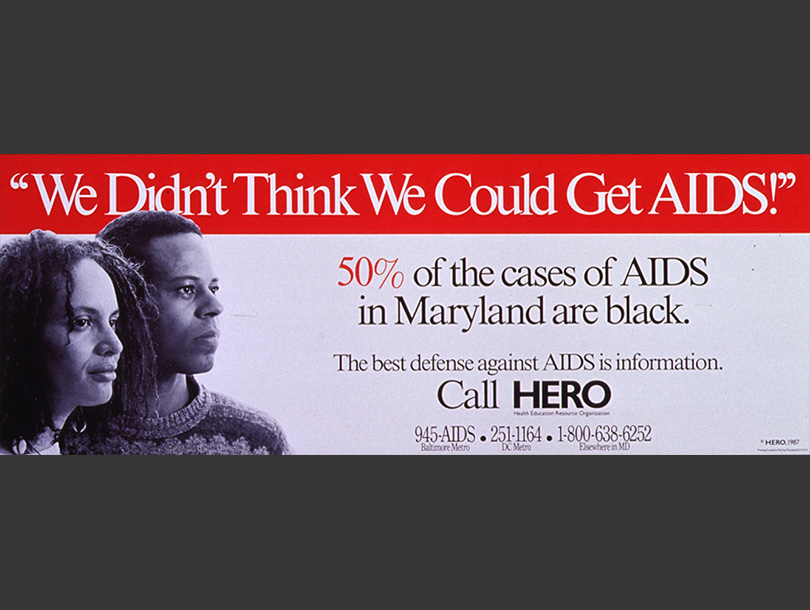

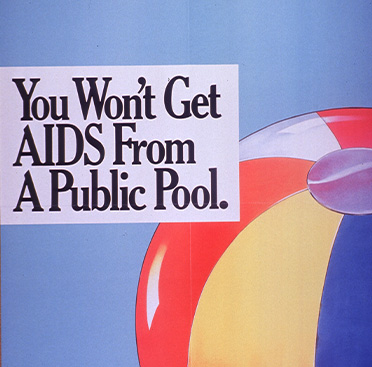

Since the first announcements about AIDS appeared in the early 1980s, myths have persisted alongside the epidemic, and rumors have accompanied emerging scientific ideas about the disease. First was the powerful stigma attached to the 4 H’s—homosexuals, Haitians, hemophiliacs, and heroin-IV drug users—those initially believed to be at risk for contracting AIDS. Then came unfounded concerns about catching AIDS from drinking fountains, toilet seats, handshakes, and hugs. The campaigns collected here were designed by AIDS service organizations to dispel major myths about who could contract the disease and raise awareness about how it spread. By directly confronting AIDS myths and rumors, these efforts ensured that more people understood that AIDS was not a punishment or a disease that only affected “at-risk” populations: it was something that required everyone to think and respond to in healthful ways.

View images in this theme